News release

From:

WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed

27 FEBRUARY 2017 | GENEVA - WHO today published its first ever list of antibiotic-resistant "priority pathogens" – a catalogue of 12 families of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health.

The list was drawn up in a bid to guide and promote research and development (R&D) of new antibiotics, as part of WHO’s efforts to address growing global resistance to antimicrobial medicines.

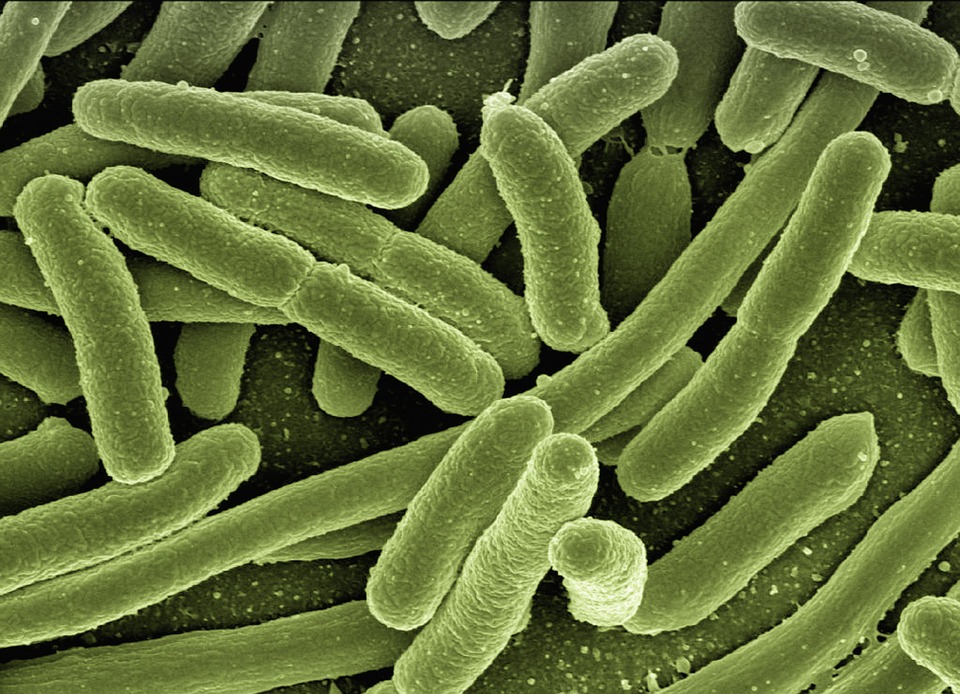

The list highlights in particular the threat of gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics. These bacteria have built-in abilities to find new ways to resist treatment and can pass along genetic material that allows other bacteria to become drug-resistant as well.

"This list is a new tool to ensure R&D responds to urgent public health needs," says Dr Marie-Paule Kieny, WHO's Assistant Director-General for Health Systems and Innovation. "Antibiotic resistance is growing, and we are fast running out of treatment options. If we leave it to market forces alone, the new antibiotics we most urgently need are not going to be developed in time."

The WHO list is divided into three categories according to the urgency of need for new antibiotics: critical, high and medium priority.

The most critical group of all includes multidrug resistant bacteria that pose a particular threat in hospitals, nursing homes, and among patients whose care requires devices such as ventilators and blood catheters. They include Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and various Enterobacteriaceae (including Klebsiella, E. coli, Serratia, and Proteus). They can cause severe and often deadly infections such as bloodstream infections and pneumonia.

These bacteria have become resistant to a large number of antibiotics, including carbapenems and third generation cephalosporins – the best available antibiotics for treating multi-drug resistant bacteria.

The second and third tiers in the list – the high and medium priority categories – contain other increasingly drug-resistant bacteria that cause more common diseases such as gonorrhoea and food poisoning caused by salmonella.

G20 health experts will meet this week in Berlin. Mr Hermann Gröhe, Federal Minister of Health, Germany says "We need effective antibiotics for our health systems. We have to take joint action today for a healthier tomorrow. Therefore, we will discuss and bring the attention of the G20 to the fight against antimicrobial resistance. WHO’s first global priority pathogen list is an important new tool to secure and guide research and development related to new antibiotics."

The list is intended to spur governments to put in place policies that incentivize basic science and advanced R&D by both publicly funded agencies and the private sector investing in new antibiotic discovery. It will provide guidance to new R&D initiatives such as the WHO/Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) Global Antibiotic R&D Partnership that is engaging in not-for-profit development of new antibiotics.

Tuberculosis – whose resistance to traditional treatment has been growing in recent years – was not included in the list because it is targeted by other, dedicated programmes. Other bacteria that were not included, such as streptococcus A and B and chlamydia, have low levels of resistance to existing treatments and do not currently pose a significant public health threat.

The list was developed in collaboration with the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Tübingen, Germany, using a multi-criteria decision analysis technique vetted by a group of international experts. The criteria for selecting pathogens on the list were: how deadly the infections they cause are; whether their treatment requires long hospital stays; how frequently they are resistant to existing antibiotics when people in communities catch them; how easily they spread between animals, from animals to humans, and from person to person; whether they can be prevented (e.g. through good hygiene and vaccination); how many treatment options remain; and whether new antibiotics to treat them are already in the R&D pipeline.

"New antibiotics targeting this priority list of pathogens will help to reduce deaths due to resistant infections around the world," says Prof Evelina Tacconelli, Head of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Tübingen and a major contributor to the development of the list. "Waiting any longer will cause further public health problems and dramatically impact on patient care."

While more R&D is vital, alone, it cannot solve the problem. To address resistance, there must also be better prevention of infections and appropriate use of existing antibiotics in humans and animals, as well as rational use of any new antibiotics that are developed in future.

WHO priority pathogens list for R&D of new antibiotics

Priority 1: CRITICAL

- Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant

- Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant, ESBL-producing

Priority 2: HIGH

- Enterococcus faecium, vancomycin-resistant

- Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and resistant

- Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin-resistant

- Campylobacter spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant

- Salmonellae, fluoroquinolone-resistant

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cephalosporin-resistant, fluoroquinolone-resistant

Priority 3: MEDIUM

- Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin-non-susceptible

- Haemophilus influenzae, ampicillin-resistant

- Shigella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Professor Ramon Shaban is the Inaugural Clinical Chair and Professor of Infection Prevention and Disease Control at the University of Sydney and Western Sydney Local Health District

The recently released WHO List of Priority Pathogens for R&D for new antibiotics identify key focal points for renewed efforts in the fight against antimicrobial resistant.

R&D into new antibiotic solutions while must go beyond new drug discovery.

First, countries around the world must formally designate antimicrobial resistance as a societal, political, health and research priority within a One Health approach.

Second, R&D should accelerate and expand infection-excluding diagnostics and technology. While technology and resources for rapid and definitive diagnosis is the ultimate goal, excluding infection-attributable injury and disease that has a reliance on antibiotics would go a long way to reducing AMR.

Third, there is a need for intense and considered focus on new and renewed countermeasures. This should include, but is not limited to, One Health vaccine development for conditions that have reliance on antimicrobials, drug discovery, rapid definitive diagnostics at both bench and bedside, utility of non-classic pharmacological interventions and the standardisation of laboratory testing.

Fourth, we must extend the evidence and practice base that we know works (or not as the case may be) in human health and non-health related context into animal, agricultural and environment sectors for a truly One Health approach.

Finally, we must harness existing and new knowledge into human factors and behaviour modification to bring about whole of societal change within a One Health approach. This should focus on existing evidence base for non-infection control and non-health to effect changes in human factors for reliance on antibiotics for all populations across the lifespan and across One Health.

AMR is not, and can no longer be considered, a problem for just for clinicians in human sectors. It is a whole of society challenge, and many of the solutions are non-clinical. It, like infection control, is everyone’s business

Associate Professor Rietie Venter is the Head of Microbiology at the University of South Australia

The WHO recently published their list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. In the critical list we find some of the most dangerous and antibiotic resistant pathogens.

It was one of these organisms that was responsible for the death earlier this year of an American woman as the organism was resistant to every available antibiotic in the US.

Consider also pan-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae that, apart from being extremely resistant against antibiotics, also have the cunning ability to thrive in the disinfectants used in hospitals.

These organisms are resistant to our last resort antibiotics, the carbapenems leaving only colistin as a treatment option. Colistin resistance is also increasing rapidly in these organisms though so unless we take urgent action, we will soon be faced with a tide of highly resistant, untreatable infections and the post-antibiotic era would be a dire reality.

The publication of this list by the WHO is therefore critically important. However, research into new antimicrobials are still very poorly supported by pharmaceutical companies.

We can only hope that the publication of this list would translate into the necessary funding to develop new antimicrobials and prevent us from slipping into a world without effective antimicrobials where small injuries would once again be life-threatening and modern medicine such as transplants would be impossible to practice.

Dr Maurizio Labbate is a Senior Lecturer in Microbiology at the University of Technology Sydney. He is also an author on an Australian Academy of Science report on antimicrobial resistance

Myself and my colleagues at the Australian Academy of Science put together a report on antimicrobial resistance a few weeks ago (https://www.science.org.au/think-tanks/risky-world).

https://www.science.org.au/think-tanks/risky-world

In it we make recommendations on how to best tackle this antimicrobial resistance and highlight the main drivers. We argue that this problem is a One Health issue, specifically that human, animal and environmental health are closely linked and that a multi-disciplinary and multi-pronged approach is required.

Moving forward, new antibiotics are very important but how we use them is just as important to ensure they remain active for the longest possible time. This requires extensive stakeholder engagement and behavioural change

Dr Mark Blaskovich is from the Centre for Superbug Solutions at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at The University of Queensland.

“CO-ADD tests compounds against five of the top pathogens listed on the WHO priority list for R&D of new antibiotics: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as the fungi Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans.”

“We welcome the published list of priority pathogens to be worked on from the World Health Organization. Our research targets six of the pathogens listed, including the three most critical. This will be a vital tool that will guide antibiotic research and drug discovery for the future.”

Note: The team have also recently modified and created an improved version of the antibiotic vancomycin to increase its potency and reduce its toxic side effects. Vancomycin has killing ability against WHO priority pathogens Enterococcus faecium (HIGH), Staphylococcus aureus (HIGH) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (MEDIUM). They are also working on a rapid bacterial diagnostic that would reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics, a key cause driving the increase in resistance.

WHO priority pathogens list for R&D of new antibiotics

Priority 1: CRITICAL

Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant (CO-ADD)

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant (CO-ADD)

Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant, ESBL-producing (CO-ADD – Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae)

Priority 2: HIGH

Enterococcus faecium, vancomycin-resistant (Vanco-program)

Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and resistant (CO-ADD) (Vanco-program)

Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin-resistant

Campylobacter spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant

Salmonellae, fluoroquinolone-resistant

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cephalosporin-resistant, fluoroquinolone-resistant

Priority 3: MEDIUM

Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin-non-susceptible (Vanco-program)

Haemophilus influenzae, ampicillin-resistant

Shigella spp., fluoroquinolone-resistant

A/Prof Penelope Bryant is a Group Leader and Honorary Fellow in Infection and Immunity at Murdoch Childrens Research Institute

It’s a dirty little secret that the antibiotic pipeline is drying up and there are hardly any new ones to fight multi-resistant bacterial infections. It costs a lot of money to develop a drug, so the WHO releasing this list of urgent priority bugs is an important call to action to develop new antibiotics to prevent more deaths.

As important as new antibiotics are, to stop the rise in resistant infections we need to do more. We need to stop the spread of infections and we need to preserve our current antibiotics by using them better. This means not using antibiotics for viral infections and using shorter courses of antibiotics where it is safe to do so.

We have previously found that up to a quarter of antibiotics in children are prescribed incorrectly. The Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Infectious Diseases Antimicrobial Stewardship group has provided guidelines for improving antibiotic prescribing in children. We can all do better.

Professor Karin Thursky, Deputy Head, Infectious Diseases, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre; Director, of National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship (NCAS); Director, Guidance, Doherty Institute.

A key plank of the fight against antimicrobial resistance is surveillance of the usage of antimicrobials – in hospitals, in primary care (GPs), in veterinary medicine, and in the aged-care sector. In Australia, since 2013, we have been annually conducting the National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (NAPS) in hospitals, which has continually highlighted areas in which antimicrobials have been inappropriately prescribed. We have developed decision-support software that enables doctors, nurses, pharmacists and infection control practitioners in hospitals to systematically monitor and manage antimicrobial prescribing. 67 hospitals in Australia currently use our approvals and decision-support software, Guidance. For the aged-care sector, we have now successfully piloted the Aged-Care NAPS, and are hoping to significantly expand this program going forward. We know from our preliminary data that in aged-care homes, antimicrobial prescribing is at very high levels and is often inappropriate. In respect of primary care and veterinary medicine, we do not currently have the resources, or have not yet set up systems, to undertake surveys in these critical sectors, although significant effort is being channelled in this direction. It is crucial that we build on what we have achieved so far in surveillance by comprehensively covering all these four key sectors. This is what the Australian government’s One Health approach entails.

Associate Professor Kirsty Buising, Deputy Director of National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship (NCAS) and Royal Melbourne Hospital Infectious Diseases Physician, Director, Guidance, Doherty Institute.

It is extremely important that new antimicrobials are developed to treat infections that are caused by pathogens that are resistant to currently available antimicrobial drugs. However, we also need to focus on ensuring that the antimicrobial drugs that we do have, remain effective in the future. We know that many antimicrobial drugs are currently being used in inappropriate ways, indeed sometimes in situations where they are completely unnecessary. This is contributing to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance amongst microbial pathogens.

The concept of antimicrobial stewardship is predicated on the idea that we can undertake activities to reduce the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, and encourage clinicians to prescribe these drugs more judiciously. It is about enabling prescribers to choose the right drugs when they are necessary, and taking action to minimize unnecessary or inappropriate use.

Prof Liz Harry is Director of The ithree institute at the University of Technology, Sydney

The WHO list of antibiotic resistant priority pathogens sends a clear message that we have a serious health problem of global proportions. It was only a matter of time before this happens. Gram-negative bacteria are the biggest threat currently as they have an intrinsic ability to resist killing by antibiotics and are able to transfer the genetic information that gives them this ability to other bacteria within a matter of minutes.

Last year in Australia, the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released its first national antimicrobial resistance strategy. It has since developed national surveillance surveys of AMR and antibiotic use in human health, animal health and agricultural settings. This is an important first step in getting a handle on the scale and severity of the issue. Now we need serious investment and policies to get action on new treatments that are both effective for these infections caused by antibiotic bacteria as well as minimize the rate of resistance to them. This is a research challenge we can only hope to meet with serious investment and commitment.

At the i3 institute we focus on understanding how bacteria adapt and survive in their host. We have identified several new mechanisms that represent opportunities for targeting with new antibiotics. We are currently developing these antibiotics. It takes about 10 years and a commitment of funding if we are to win this battle. a But it is not just about developing new antibiotics. We can now use technology to determine what underpins a stable microbial ecosystem and find other tools and mechanisms to moderate and maintain this balance.

This is a problem that is not too late to tackle. The stop smoking campaign is a great analogy that can be applied to reducing the antimicrobial resistance crisis.

Associate Professor Peter Speck is from the School of Biological Sciences at Flinders University.

There is strong evidence that the antibiotic era is drawing to a close. Bacterial pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus 'golden staph', are becoming increasingly resistant to all antibiotics. The UK Government O’Neill Report estimates that by 2050 antimicrobial resistance will kill 10 million people/year, at a total economic cost of US$100 trillion. For context, cancer kills 8 million people/year worldwide. While the antibiotic discovery pipeline is virtually empty, bacteriophages ('phages', viruses that infect and kill bacteria) represent a potential solution in many clinical settings.

Phage therapy is not a new idea, having been shown to be safe and effective in almost 100 years of extensive use in Russia, however in the western world they have historically been overlooked in favor of the now-failing antibiotics.

Research carried out by Flinders University, in collaboration with the University of Adelaide and commercial partner AmpliPhi Biosciences Corporation, has provided preliminary data showing that phages against golden staph are safe and effective against this infection in chronic rhinosinusitis. To advance this research requires the funding to carry out further clinical trials.

The challenge of antibiotic resistance demands that governments worldwide dramatically increase efforts to develop new approaches effective against bacterial infections.

Professor Peter Collignon AM is an Infectious Diseases Physician and Microbiologist. He is a Professor in the Medical School at the Australian National University.

This WHO list is very important to help Pharmaceutical companies, researchers, drug regulators and governments to help set priorities for research to find new drug classes to treat life threatening infections where there are few and in some cases, no antibiotics to treat these infections.

Antibiotic resistance is an ever growing problem. In the developing world half of some common infections such as E.coli are now untreatable with available agents. The most resistant bacteria presently are Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas plus bowel bacteria such as E.coli and Klebsiella. The WHO list gives appropriate priority to the different bacteria.

Michael Gillings is Professor of Molecular Evolution in the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University

The WHO has just generated a hit list of bacteria that pose critical risks to humanity. These bacteria are deadly, are difficult to cure, and spread easily between people and animals. Most importantly, they are resistant to the antibiotics that we normally use to kill bacterial infections.

The most worrying group include organisms that infect patients undergoing treatment in hospitals or nursing homes. They have become resistant to last resort antibiotics. Unless we do something soon, it is estimated that the death toll for antibiotic resistant infections might reach 10 million per year by 2050; more than the global toll for cancer.

Developing new antibiotics is expensive, and often not profitable. However, the WHO hopes that this statement will stimulate much needed research and development of next generation antibiotics. In the meantime, we can all play a part by using existing antibiotics wisely and by better infection control.

International

International