Media release

From: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA)Large freshwater find off Canterbury coast

Scientists have discovered an extensive body of freshwater off the Canterbury coast between Timaru and Ashburton.

NIWA marine geologist Dr Joshu Mountjoy says the discovery is one of the few times a significant offshore aquifer has been located around the world and may lead to a new freshwater resource for the region.

The aquifer lies just 20 metres below the seafloor, making the find one of the shallowest in the world. It extends up to 60 kilometres from the coastline and may contain as much as 2000 cubic kilometres of water which is equivalent to half the volume of groundwater across Canterbury.

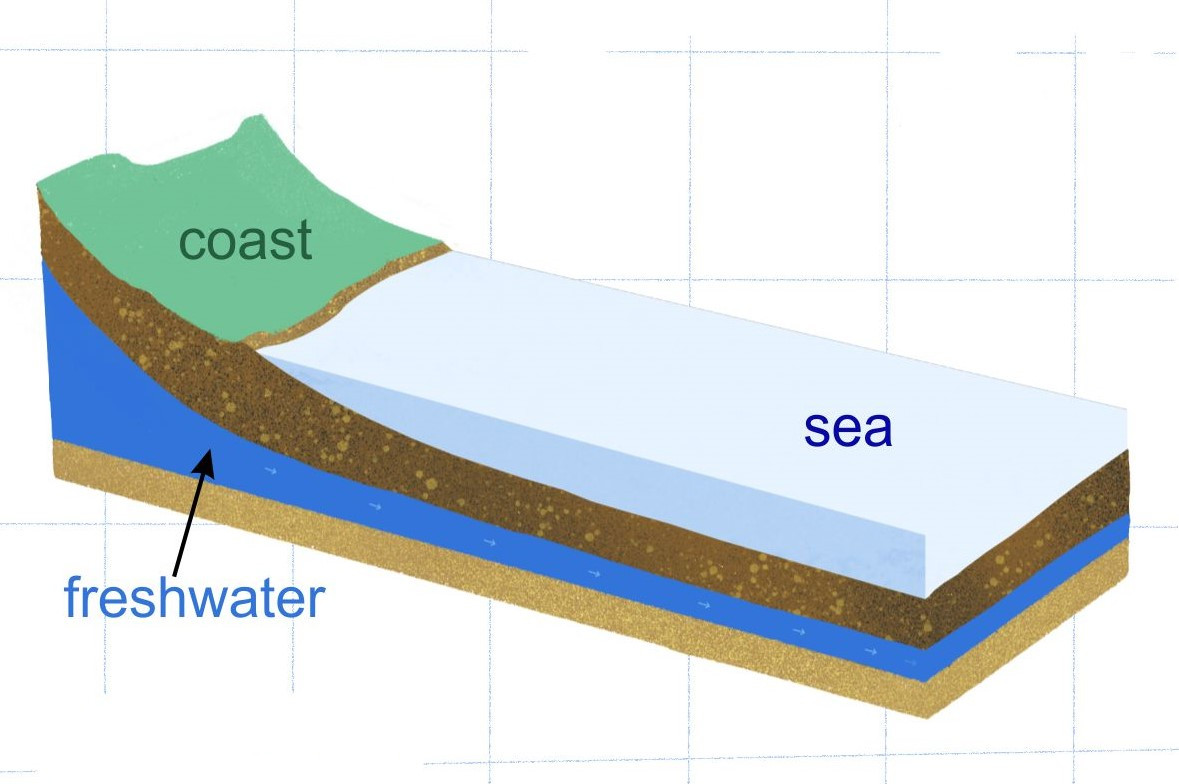

Derived from rainfall, the aquifer is partly being replenished by groundwater flow from the coastline between Timaru and Ashburton. However, most of the freshwater became trapped offshore during the last three Ice Ages, when sea level was more than 100 metres lower than it is today.

First indications that the offshore groundwater was there was a chance find that arose when a scientific drilling project in 2012 found brackish water – or salt and freshwater mixed together – 50km off the coast and about 50m below the seafloor.

Dr Mountjoy says that discovery led to a 2017 voyage aboard NIWA research vessel Tangaroa to carry out further investigation in which scientists collected electromagnetic data. An electrical source was towed behind the ship and behind that was a line of receivers which record different signals depending on the electrical resistivity of the ground. Resistivity is strongly influenced by the amount of salt in the water locked up in sediments beneath the seafloor. This was then integrated with seismic reflection profiling and numerical modelling to determine the amount of freshwater beneath the seabed.

The findings have been published today in leading scientific journal Nature Communications.

“One of the most important aspects of this study is the improved understanding it offers to water management,” Dr Mountjoy says.

“If you’re going to manage the groundwater on shore and near the coast, you need to understand what the downstream limits are.”

The project attracted funding from the European Research Council through the MARCAN project which is a five-year international programme investigating how offshore groundwater influences continental margins.

The structure of the aquifer has been mapped in 3D and reveals complex variations in shape and salinity, according to paper lead-author Aaron Micallef of the University of Malta who also says the approach to characterising this aquifer could potentially be used to revise estimations of their number and volume globally.

Dr Mountjoy says while there are other places where offshore groundwater is known about, this is only the second time such intensive surveying has been carried out to define the extent of the water body. “By defining how big it is we’re getting a handle on understanding it.”

The next step is to take samples for analysis. “At the moment we have used remote techniques, modelling and geophysics. We really need to go out there and ground-truth our findings and we are investigating options for that.”

Dr Mountjoy says there are several places around New Zealand facing significant issues with their groundwater, such as Christchurch and Hawke’s Bay which are feeling the pressure of increasing populations and regular prolonged dry periods.

“Hawke’s Bay is an example of a region needing to manage what they’re dealing with onshore. They’ve only got half the picture if they don’t know how far out it goes, and how much is leaking into the ocean.

“We need to set the groundwork in place for the future. Our primary goal is to help people manage their onshore resources. Our groundwater systems are a critical resource for society, they are increasingly under pressure, and we need every bit of information we can get.”

The study is an outcome of the MARCAN project and was funded by the European Research Council, the NZ Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, US National Science Foundation and the German Research Foundation.