Media Release

Radiotherapy enhances skin cancer’s resistance to anti-tumor immune responses

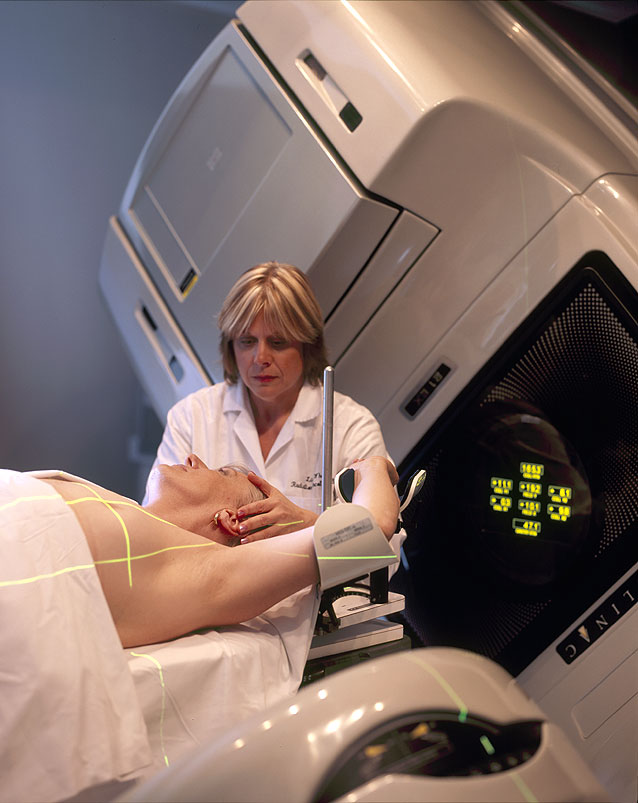

Radiotherapy can paradoxically induce local suppression of the immune system and thus diminish anti-tumor immune responses, according to new research published this week in Nature Immunology. These findings urge caution in the use of radiotherapy for the treatment of skin tumors.

Ionizing radiation is used to eliminate tumor mass, but it can also interfere with the immune system’s anti-cancer responses. Miriam Merad and colleagues show that irradiation mobilizes cells of the immune system located in the skin, known as ‘Langerhans cells’ (LCs). Unlike other cells that die in response to ionizing radiation, LCs can resist the effects of irradiation through their enhanced ability to rapidly repair DNA damage, due in part to their higher expression of the cell cycle–inhibitor CDKN1A (p21). The authors show that mice bearing p21-deficient LCs have better anti-tumor responses than those of wild-type mice.

In a series of experiments, the researchers show that LCs take up cell debris triggered by irradiation, including tumor proteins, and migrate to draining lymph nodes. Here, LCs stimulate immunosuppressive regulatory T cells. These regulatory T cells prevent the activation of anti-tumor immune responses and thereby promote resistance among any tumor cells that survived the radiation treatment.

In an accompanying News & Views, Laurence Zitvogel and Guido Kroemer write that the results “suggest that whenever possible, irradiation of major skin areas should be avoided so that a minimum number of LCs (which are present solely in the epidermis) are mobilized for immunosuppression.”

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Professor Grant McArthur is Associate Director of Cancer Research, Consultant Medical Oncologist, Co-Head Cancer Therapeutics Program, and Director Melanoma and Skin Service at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. He is also Lorenzo Galli Chair in Melanoma and Skin Cancers at the University of Melbourne