Media Release

From: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA)Scientists say methane emitted by humans ‘vastly underestimated’

NIWA researchers have helped unlock information trapped in ancient air samples from Greenland and Antarctica that shows the amount of methane humans are emitting into the atmosphere from fossil fuels has been vastly underestimated.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and a large contributor to global warming. Its atmospheric levels have increased by about 150 per cent over the past 300 years. It is responsible for about 25 per cent of global warming to date.

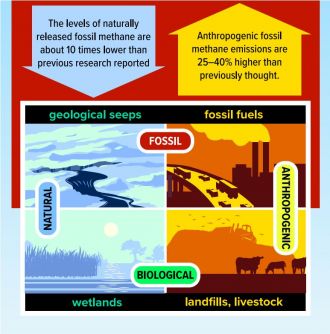

However, in a paper published this week in leading scientific journal Nature, researchers from the University of Rochester in the US outline that the amount of methane in the atmosphere that can be attributed to anthropogenic fossil sources is 25-40 per cent higher than previously estimated.

The authors say the findings are significant because it means reducing emissions from fossil fuel extraction and use will have a greater impact on curbing future global warming than scientists previously thought.

Drs Benjamin Hmiel and Vasilii Petrenko describe how ice cores act as time capsules, trapping small quantities of ancient air. That air was then extracted as a first step in determining whether the methane emitted was a result of human activity or occurred naturally.

Some of those air samples were sent to NIWA’s Wellington laboratory where they were subjected to a complex and precise process to extract the methane. NIWA principal atmospheric technician and co-author of the Nature paper, Tony Bromley, says further analysis was then carried out in a machine called a mass spectrometer which “fingerprints” methane sources according to the measured content of the rare, radioactive isotope radiocarbon.

For every single measurement, the team had drilled out one ton of ice while working in polar environments. From that they extracted the equivalent of 5 household buckets of air, and then isolated the equivalent volume of 1 water drop of methane. In that methane, only one in a trillion molecules is radiocarbon and they measured the changes in that minuscule content.

Mr Bromley says the degree of accuracy provided by the NIWA analysis means it is possible to pinpoint exactly how much methane is produced by humans.

Previously it has been difficult for researchers to determine exactly where methane emissions originate – biological methane can be released from sources such as wetlands or landfills, rice fields and livestock. Fossil methane can be emitted through natural geological seeps or as a result of humans extracting and using fossil fuels including oil, gas and coal.

The two types of methane can be distinguished, because biological methane contains measurable amounts of radiocarbon. In fossil methane, all the radiocarbon has decayed away while the gas was stored in underground reservoirs. However, radiocarbon measurements in modern air cannot separate fossil methane that is emitted naturally from industrial sources.

“As a scientific community we’ve been struggling to understand exactly how much methane we as humans are emitting into the atmosphere,” says Dr Petrenko.

“We know that the fossil fuel component is one of our biggest component emissions, but it has been challenging to pin that down because in today’s atmosphere, the natural and anthropogenic components of the fossil emissions look the same, isotopically.”

By measuring the methane radiocarbon from more than 200 years ago when there were no industrial sources, the researchers knew that all fossil methane had to be emitted naturally. They found that almost all of the methane emitted to the atmosphere was biological until about 1870. That’s when the fossil component began to rise rapidly. The timing coincides with a sharp increase in the use of fossil fuels.

They also discovered the levels of naturally released fossil methane are about 10 times lower than previous research reported.

Methane being emitted by human activity is the second largest contributor to global warming, after carbon dioxide. But, compared to carbon dioxide, methane has a relatively short shelf-life; it lasts an average of only nine years in the atmosphere, while carbon dioxide can persist in the atmosphere for about a century. That makes methane an especially suitable target for curbing climate change in a short time frame.

“If we stopped emitting all carbon dioxide today, high carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere would still persist for a long time,” Dr Hmiel says.

“Methane is important to study because if we make changes to our current methane emissions, it’s going to reflect more quickly.”

As well as NIWA, the research was a collaboration with scientists from several countries and institutions including the US, Australia, France and Switzerland. The study was supported by the US National Science Foundation and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation.