Media release

From:

A new study has revealed that prehistoric kangaroos in southern Australia had more general diet than previously assumed, giving rise to new ideas about their survival and resilience to climate change, and the final extinction of the megafauna.

The new research, a collaboration between palaeontologists from Flinders University and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), used advanced dental analysis techniques to study microscopic wear patterns on fossilised kangaroo teeth.

The findings, published by the international journal Science, suggest that many species of kangaroos were generalists, able to adapt to diverse diets in response to environmental changes.

The research focused on fossil kangaroo species from the renowned Victoria Fossil Cave at the Naracoorte Caves World Heritage Area in South Australia and refutes the long-held idea that those species that did not survive past 40,000 years ago became extinct because they had specialised diets.

The Naracoorte Caves World Heritage Area of southeastern South Australia contains the richest and most diverse deposit of fossil kangaroos known from the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 12,000 years ago).

Lead researcher Dr Sam Arman, from MAGNT and Flinders University, explained the significance of these findings.

“Our study shows that most prehistoric kangaroos found at Naracoorte had broad diets. This dietary flexibility likely played a key role in their resilience during past changes in climate.”

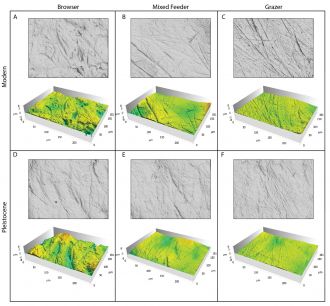

Using Dental Microwear Texture Analysis, the team - including Flinders University Professor Gavin Prideaux and Grant Gully - compared the diets of 12 extinct species with those of 17 modern species. The results contradict previous assumptions that certain species went extinct due to their specialised diets. Instead, the study found that most species were mixed feeders, capable of consuming a combination of shrubs and grasses.

Professor Prideaux, from the Flinders Palaeontology Lab, says the wider implications of these findings indicate that the distinctive short-faced kangaroo anatomy led to a widespread view that sthenurines were unable to adapt their diets when climate change altered vegetation patterns, leading to their extinction.”

“Most of the Naracoorte kangaroo species actually had similar everyday diets, which would reflect foods that were most nutritious and readily accessible.”

Dr Arman adds: “Having the hardware to eat more challenging foods would have helped them get through seasons or years when their preferred food was rare.

"An analogy might be my 4x4. Most of the time, I don’t need to engage four-wheel drive, but this capability becomes crucial when I do need it.”

The study represents a successful partnership between Flinders University and MAGNT, combining innovative techniques with expertise in palaeontology to deepen our understanding of Australia’s unique prehistoric ecosystems.

Multimedia

Australia; SA

Australia; SA