News release

From:

A little protein with a big role in building Earth’s carbon‑fixing machinery

New research shows how a low‑abundance adaptor protein enables construction of carboxysomes, the microcompartments that house Rubisco - the most abundant protein on Earth

An international team of scientists has discovered that a small, low‑abundance protein plays a surprisingly big role in assembling carboxysomes - specialised bacterial microcompartments that enable efficient carbon fixation and underpin much of life on Earth.

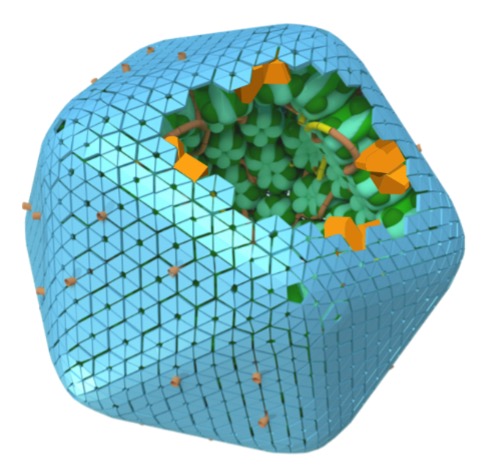

The study, in Nature Plants, reveals how the shell adaptor protein ApN (also known as CcmN), despite being present at very low abundance, is essential for orchestrating the early stages of carboxysome formation. The research shows that ApN helps organise the outer layer of a biomolecular condensate (a liquid-like droplet of proteins) creating the necessary prelude to construction of the protein shell that ultimately enables carboxysome function.

Carboxysomes are found in cyanobacteria and encapsulate the enzyme Rubisco, the most abundant protein on the planet and the primary entry point of carbon dioxide into the biosphere. Carboxysomes are encapsulated by a protein shell that helps trap CO2 gas and elevate its concentration. By concentrating CO2 around Rubisco, carboxysomes dramatically enhance the efficiency of photosynthesis.

Carboxysomes are natural “carbon‑capturing machines” that help many microbes pull carbon dioxide out of the air. By understanding how these structures are built (especially the role of a tiny protein that turns out to be essential) we can gain a better understanding of how we can copy this system in crop plants to enhance photosynthesis.

This could one day make plants grow faster and use water more efficiently, helping farmers produce more food with fewer resources. It may also inspire new technologies for capturing carbon from the atmosphere, offering potential benefits for climate and environmental sustainability.

A low‑abundance protein with an outsized impact

Using a combination of biochemistry, cryo‑electron microscopy, structural modelling and in vivo experiments, the researchers discovered that ApN forms a previously unknown complex with the carboxysome condensate protein CcmM. This complex localises to the outer edges of a Rubisco‑rich biomolecular droplet, positioning ApN precisely where the carboxysome shell will later assemble.

“Because ApN is small and present at low abundance, it seems surprising that it can play such an important role,” the authors explain. “Instead, we show that it acts as a critical organiser, ensuring that shell construction only occurs after the enzymatic core of the carboxysome is correctly assembled.”

This stepwise mechanism ensures that the protein shell forms at the right time and in the right place. Without ApN, carboxysomes fail to mature properly, even though the core enzymes can still cluster together to form a liquid droplet.

Why this matters for crops and climate

Understanding how carboxysomes assemble is not only a fundamental biological question. Carboxysomes are central to the cyanobacterial CO2‑concentrating mechanism (CCM), which allows cyanobacteria to fix carbon far more efficiently than most crop plants.

There is strong global interest in introducing carboxysomes, or carboxysome‑like systems, into plant chloroplasts as a way to improve photosynthetic efficiency and increase crop productivity - an approach with enormous potential benefits for agriculture and food security.

“This work gives us a much clearer blueprint for how beta-carboxysomes are built,” said Dr Ben Long from the University of Newcastle, a co‑author on the study. “If we want to engineer these structures into plant chloroplasts, we need to understand not just which proteins are required, but how low‑abundance components like ApN control the assembly process.”

International collaboration

The research was a multi‑institutional effort, with contributions from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, the Australian National University, and the University of Newcastle. The study integrates cutting‑edge structural biology with cellular and physiological analysis to link molecular mechanism with biological function.

Australia; International; NSW; ACT

Australia; International; NSW; ACT