News release

From:

Peer-reviewed Experimental study Cells

Unearthing how a carnivorous fungus traps and digests worms

New study examines molecular process at play through each stage of predation

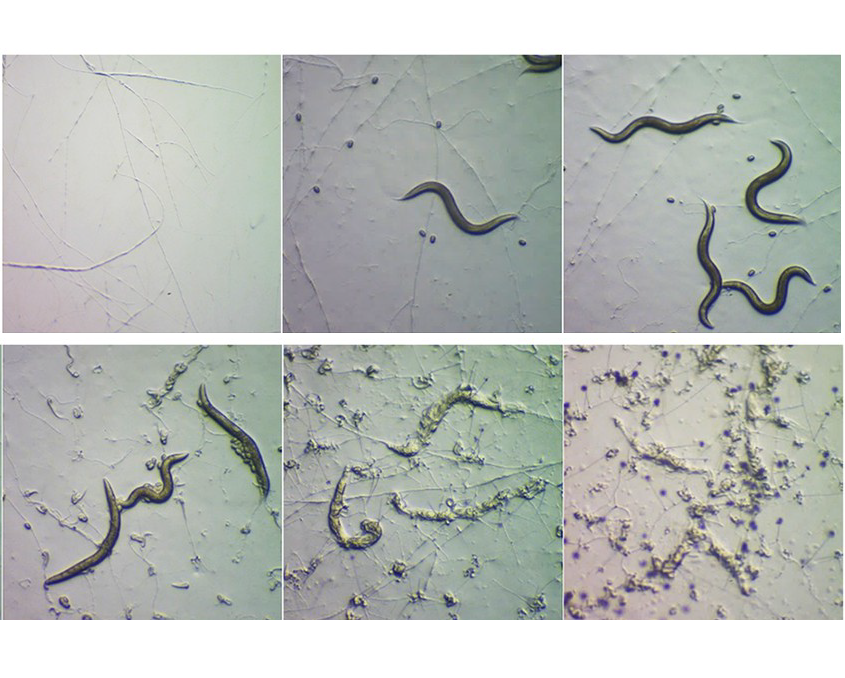

A new analysis sheds light on the molecular processes involved when a carnivorous species of fungus known as Arthrobotrys oligospora senses, traps and consumes a worm. Hung-Che Lin of Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, and colleagues present these findings November 21st in the open access journal PLOS Biology.

A. oligospora usually derives its nutrients from decaying organic matter, but starvation and the presence of nearby worms can prompt it to form traps to capture and consume worms. A. oligospora is just one of many species of fungi that can trap and eat very small animals. Prior research has illuminated some of the biology behind this predator-prey relationship (such as certain genes involved in A. oligospora trap formation) but for the most part, the molecular details of the process have remained unclear.

To boost understanding, Lin and colleagues performed a series of lab experiments investigating the genes and processes involved at various stages of A. oligospora predation on a nematode worm species called Caenorhabditis elegans. Much of this analysis relied on a technique known as RNAseq, which provided information on the level of activity of different A. oligospora genes at different points in time. This research surfaced several biological processes that appear to play key roles in A. oligospora predation.

When A. oligospora first senses a worm, the findings suggest, DNA replication and the production of ribosomes (structures that build proteins in a cell) both increase. Next, the activity increases of many genes that encode proteins that appear to assist in the formation and function of traps, such as secreted worm-adhesive proteins and a newly identified family of proteins dubbed “trap enriched proteins” (TEP).

Finally, after A. oligospora has extended filamentous structures known as hyphae into a worm to digest it, the activity is boosted of genes coding for a variety of enzymes known as proteases—in particular, a group known as metalloproteases. Proteases break down other proteins, so these findings suggest that A. oligospora uses proteases to aid in worm digestion.

These findings could serve as a foundation for future research into the molecular mechanisms involved in A. oligospora predation and other fungal predator-prey interactions.

The authors add, “Our comprehensive transcriptomics and functional analyses highlight the role of increased DNA replication, translation, and secretion in trap development and efficacy. Furthermore, a gene family that is largely expanded in the genomes of nematode-trapping fungi were found to be enriched in traps and critical for trap adhesion to nematodes. These results furthered our understanding of the key processes required for fungal carnivory.”

International

International