News release

From:

Researchers have created a process using liquid metals, powered by sunlight, that can produce clean hydrogen from both freshwater and seawater.

The method allows researchers to ‘harvest’ hydrogen molecules from water while also avoiding many of the limits in current hydrogen production methods. It offers a new avenue of exploration for producing green hydrogen as a sustainable energy source.

Hydrogen as a green energy fuel has long been the focus of countless scientists and industries. Researchers have been on the hunt for decades to find the most economical method to produce green hydrogen reliably to power the energy, transport, and manufacturing and agriculture industries, transforming production across multiple sectors of the global economy.

“We now have a way of extracting sustainable hydrogen, using seawater, which is easily accessible while relying solely on light for green hydrogen production,” said lead author and PhD candidate Luis Campos.

Senior researcher Professor Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, from the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, says the study is a stunning showcase of how the natural chemistry of liquid metals can create hydrogen. His team produced hydrogen with a maximum efficiency of 12.9 percent, the team is currently working to improve the efficiency for commercialisation.

“For the first proof-of-concept, we consider the efficiency of this technology to be highly competitive. For instance, silicon based solar cells started with six percent in the 1950s and did not pass 10 percent till the1990s.”

“Hydrogen offers a clean energy solution for a sustainable future and could play a pivotal role in Australia’s international advantage in a hydrogen economy,” says project co-lead Dr. Francois Allioux.

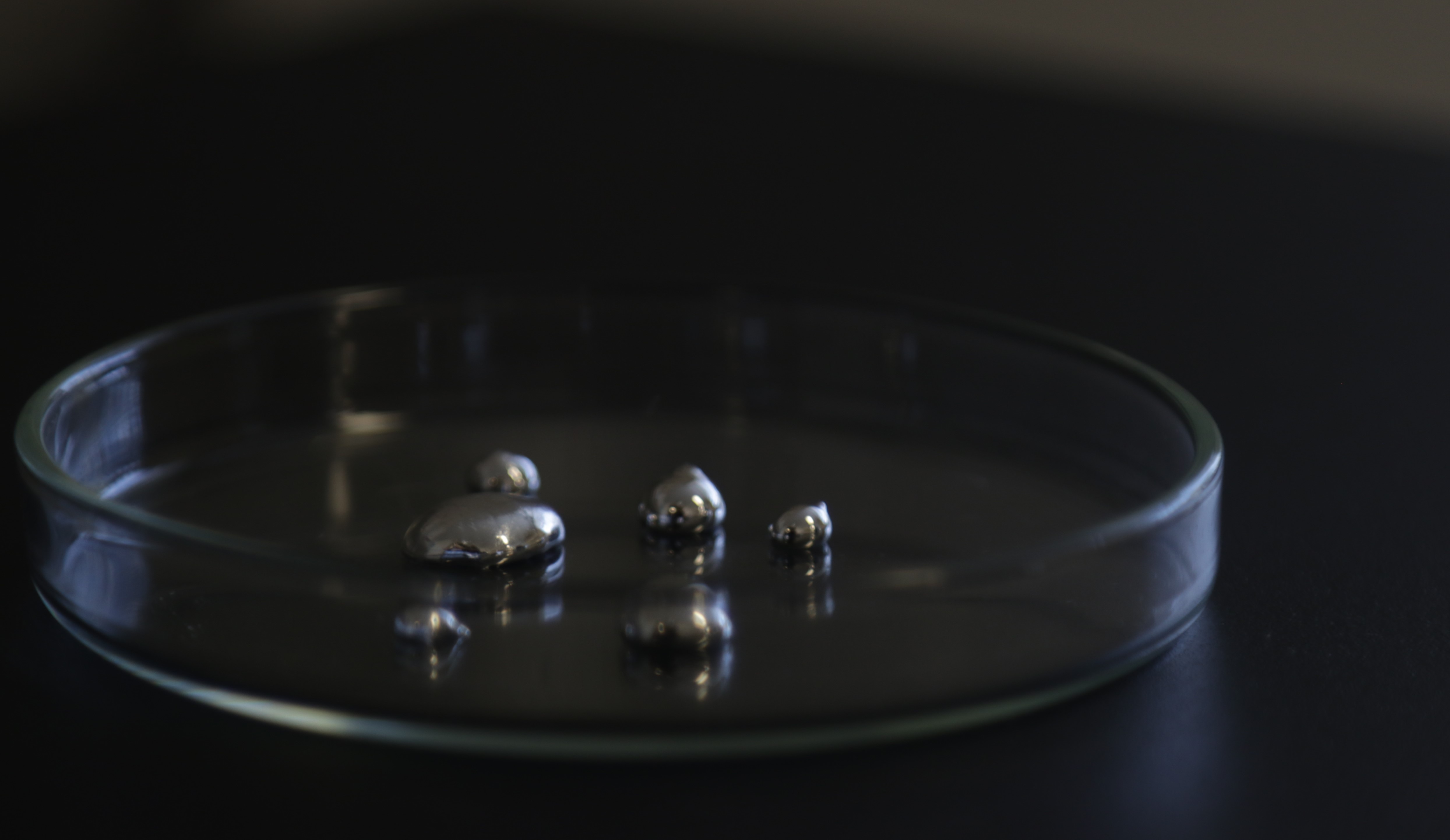

At the technology’s heart is gallium, a metal with a low melting point, meaning it needs less energy to transition from a solid into a liquid. Professor Kalantar-Zadeh’s team has been pushing the chemical and technical boundaries of liquid metals to create new materials for years. Gallium particles’ ability to absorb light caught their attention.

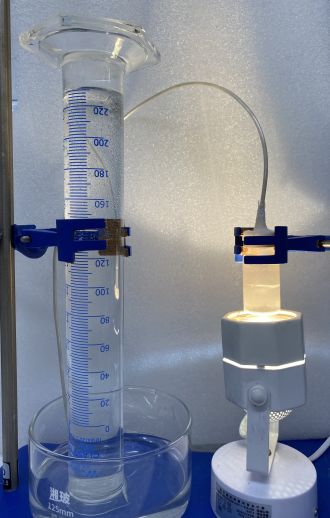

The result of this finding was a technology using a circular chemical process: particles of gallium are suspended in either seawater or freshwater and activated under sunlight or artificial light. The gallium reacts with the water to become gallium oxyhydroxide and releases hydrogen.

“After we extract hydrogen, the gallium oxyhydroxide can also be reduced back into gallium and reused for future hydrogen production – which we term a circular process,” says Professor Kalantar-Zadeh.

Gallium in liquid state is a fascinating element. At room temperature it looks like solid metal, but when heated to body temperature it transforms into liquid metallic puddles.

Mr Campos said the surface of liquid gallium is very chemically ‘non-sticky,’ and most materials will not attach to it under normal conditions. But when exposed to light in water, liquid gallium reacts at its surface, gradually oxidising and corroding. This reaction creates clean hydrogen and gallium oxyhydroxide on its surface.

“Gallium has not been explored before as a way to produce hydrogen at high rates when in contact with water - such a simple observation that was ignored previously,” says Professor Kalantar-Zadeh.

The University of Sydney led research was published in Nature Communications.

Why scientists are so keen on hydrogen molecules

Many industries and scientists believe hydrogen is the ideal candidate for a sustainable energy source, contributing significantly to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. ‘Green’ hydrogen, as its name suggests, is made using renewable sources.

Hydrogen is one of the most abundant elements on Earth and can be sourced from a large range of compounds as well, such as water (water has two hydrogen molecules). When hydrogen burns, it produces no pollutants, only water, but still can generate high levels of energy or power.

Efforts to produce green hydrogen have focused on ‘water splitting’: splitting atoms in water molecules to release hydrogen using methods including electrolysis, photocatalysis, and plasma (artificial lightning).

But the process required to separate hydrogen and oxygen atoms in water has faced multiple obstacles including the need to use purified water, incurring high cost or producing low yields of hydrogen.

The method Professor Kalantar-Zadeh’s team introduced with liquid gallium avoids many of those obstacles. The method can use both sea and fresh water and because the process is circular gallium in the reaction can be re-used.

Professor Kalantar-Zadeh said: “There is a global need to commercialise a highly efficient method for producing green hydrogen. Our process is efficient and easy to scale up.”

The team are now working on increasing the efficiency of the technology and their next goal is to establish a mid-scale reactor to extract hydrogen.

Declaration:

The University of Sydney has filed a patent application for the research. The work was supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project.

The research acknowledges the facilities and scientific and technical assistance of Sydney Analytical, a core research facility at The University of Sydney and Sydney Microscopy and Microanalysis, the University of Sydney node of Microscopy Australia.

Multimedia

Australia; NSW; VIC; QLD

Australia; NSW; VIC; QLD