News release

From:

Landmark 8m dig at Sulawesi cave could reveal overlap between extinct humans and us

Could we – that is, Homo sapiens – and an archaic and now-extinct species of early human have lived alongside each other on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi more than 65,000 years ago?

This is the question posed by an international team of archaeologists after several seasons of excavations at Leang Bulu Bettue, a limestone cave in the Maros-Pangkep karst area of southern Sulawesi.

And, if it turns out the answer to this conundrum confirms the overlapping timelines of our species and another type of human, could they have met and interacted with each other?

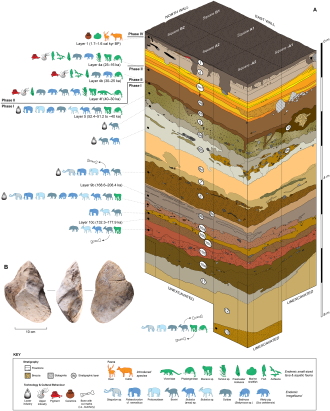

The results of this new study, led by Griffith University and published in PLOS ONE, reveal, for the first time, a deep sequence of archaeological deposits extending to at least eight metres below the current ground surface – layers that preserve traces of human activity far older than the arrival of our own species on Sulawesi.

These new discoveries build upon the team’s recent Nature publication showing archaic hominins occupied Sulawesi from at least 1.04 million years ago.

In contrast, modern humans (Homo sapiens) are thought to have reached the island at some stage prior to the initial peopling of Australia around 65,000 years ago.

“The depth and continuity of the cultural sequence at Leang Bulu Bettue now positions this cave as a flagship site for investigating whether these two human lineages overlapped in time,” said Griffith PhD candidate Basran Burhan, an archaeologist from South Sulawesi, who led the study under supervisor Professor Adam Brumm from Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution (ARCHE).

Excavations conducted since 2013, with funding from the Australian Research Council and Griffith University, revealed a uniquely long and well-preserved record of human occupation, with the deepest and oldest such evidence dating to earlier than 132,300-208,400 thousand years ago.

Among the most striking findings of this early human occupation was evidence for animal butchery and stone artefact production – including distinctive, heavy-duty stone tools known as ‘picks’ – all made long before our species had left Africa.

“These activities appear to represent an archaic hominin cultural tradition that persisted on Sulawesi well into the Late Pleistocene,” Professor Brumm said.

“By around 40,000 years ago, however, the archaeological record shows a dramatic shift.”

An earlier occupation phase, defined by cobble-based core and flake technologies and faunal assemblages dominated by dwarf bovids (anoas, labrador-sized wild cattle that are endemic to Sulawesi) alongside now-extinct Asian straight-tusked elephants, was replaced by a new cultural phase.

“This later phase featured a distinct technological toolkit, and the earliest known evidence for artistic expression and symbolic behaviour on the island – hallmarks associated with modern humans,” Basran said.

“The distinct behavioural break between these phases may reflect a major demographic and cultural transition on Sulawesi, specifically the arrival of our species in the local environment and the replacement of the earlier hominin population.”

The research team suggested Leang Bulu Bettue could provide the first direct archaeological evidence for chronological overlap – and possible interaction – between earlier humans and Homo sapiens in Wallacea.

These findings highlighted the critical importance of Sulawesi for understanding human evolution in Island Southeast Asia, and opened new avenues for exploring how different human species coexisted, adapted, then disappeared.

“That is why doing archaeological research in Sulawesi is so exciting,” Professor Brumm said.

“For example, you could dig as deep as you like at an Australian site and you’ll never find evidence for human occupation prior to the arrival of our species, because Australia was only ever inhabited by Homo sapiens.

“But there were hominins in Sulawesi for a million years before we showed up, so if you dig deep enough, you might go back in time to the point where two human species came face-to-face.”

To add to the anticipation, the team has also not yet reached the bottom of the cultural deposits at the site.

“There may be several more metres of archaeological layers below the deepest level we have excavated at Leang Bulu Bettue thus far,” Basran said.

"Further work at this site could therefore reveal new discoveries that will change our understanding of the early human story on this island, and perhaps more widely.”

The study ‘A near-continuous archaeological record of Pleistocene human occupation at Leang Bulu Bettue, Sulawesi, Indonesia’ has been published in PLOS ONE.

Multimedia

Australia; International; NSW; QLD; SA; ACT

Australia; International; NSW; QLD; SA; ACT