News release

From:

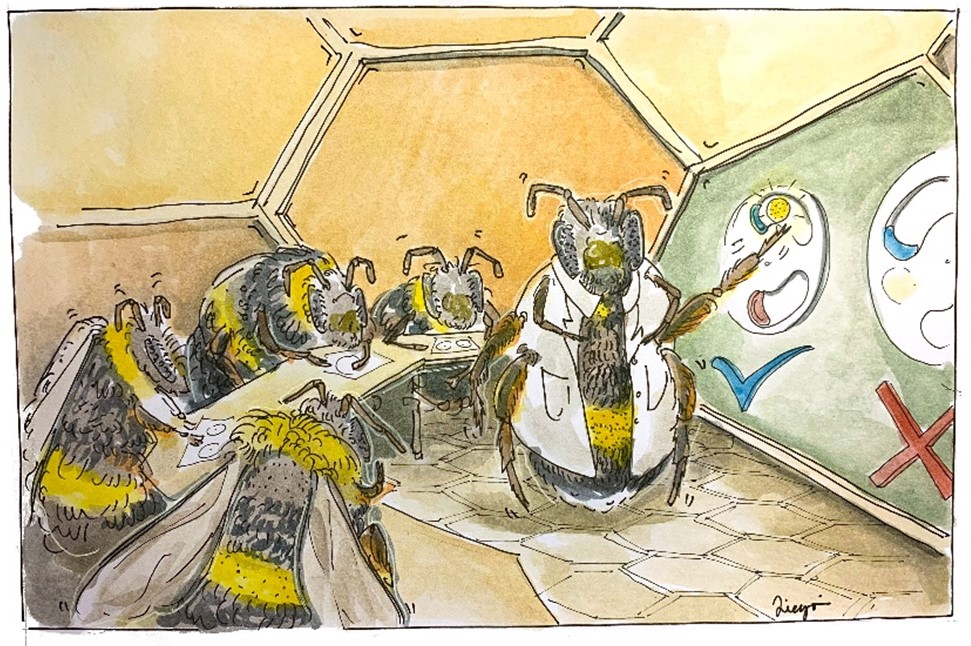

Puzzle-solving behavior spreads through bumblebee colonies

Bees that learned from others were more adept and preferred the learned solution over alternatives

Bumblebees learn to solve a puzzle by watching more experienced bees, and this behavioral preference then spreads through the colony, according to a study publishing March 7th in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Alice Dorothy Bridges and colleagues at Queen Mary University of London, UK.

Social animals like primates are skilled at learning by watching others, and previous work has shown that individual bees can learn tasks in this way, but it remained unclear whether these new behaviors would then spread through the colony. To investigate, researchers tested six colonies of bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) using a puzzle box that could be opened by rotating a lid to access a sugar solution. The bees could rotate the lid either clockwise or anticlockwise by pushing one of two different colored tabs.

The researchers trained bees to use one of these two solutions and then released these ‘demonstrator’ bees into a foraging arena alongside untrained bees and filmed them over a period of six to twelve days. Foraging bees with a demonstrator opened more puzzle boxes than control bees, and used the same puzzle solution that the demonstrator had been taught 98% of the time, suggesting that they learned the behavior socially rather than stumbling upon a solution themselves. In experiments where multiple demonstrators were each taught a different solution to the puzzle, untrained bees initially learned to use both methods, but over time they randomly developed a preference for one solution or the other, which then came to dominate in that colony.

The study is the first to document the spread of different behavioral approaches to solving the same problem in bees. The results provide strong evidence that social learning is important for the transmission of new behaviors through bumblebee colonies, as has previously been shown in primates and birds, the authors say.

Puzzle-solving behavior spreads through bumblebee colonies

Bees that learned from others were more adept and preferred the learned solution over alternatives

Bumblebees learn to solve a puzzle by watching more experienced bees, and this behavioral preference then spreads through the colony, according to a study publishing March 7th in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Alice Dorothy Bridges and colleagues at Queen Mary University of London, UK.

Social animals like primates are skilled at learning by watching others, and previous work has shown that individual bees can learn tasks in this way, but it remained unclear whether these new behaviors would then spread through the colony. To investigate, researchers tested six colonies of bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) using a puzzle box that could be opened by rotating a lid to access a sugar solution. The bees could rotate the lid either clockwise or anticlockwise by pushing one of two different colored tabs.

The researchers trained bees to use one of these two solutions and then released these ‘demonstrator’ bees into a foraging arena alongside untrained bees and filmed them over a period of six to twelve days. Foraging bees with a demonstrator opened more puzzle boxes than control bees, and used the same puzzle solution that the demonstrator had been taught 98% of the time, suggesting that they learned the behavior socially rather than stumbling upon a solution themselves. In experiments where multiple demonstrators were each taught a different solution to the puzzle, untrained bees initially learned to use both methods, but over time they randomly developed a preference for one solution or the other, which then came to dominate in that colony.

The study is the first to document the spread of different behavioral approaches to solving the same problem in bees. The results provide strong evidence that social learning is important for the transmission of new behaviors through bumblebee colonies, as has previously been shown in primates and birds, the authors say.

Bridges adds, “These results in bumblebees, which are tiny-brained invertebrates, echo those previously found using similar experiments in primates and birds - which were used to demonstrate the capacity of those species for culture.”

Bridges adds, “These results in bumblebees, which are tiny-brained invertebrates, echo those previously found using similar experiments in primates and birds - which were used to demonstrate the capacity of those species for culture.”

Multimedia

International

International