News release

From:

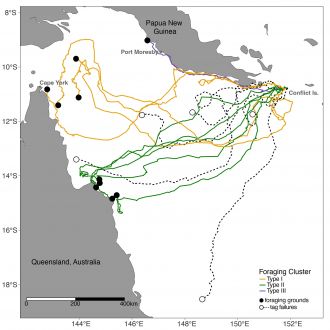

For the first time, a new study reveals that many hawksbill turtles satellite-tagged in Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) Conflict Islands swam over 1,000 km to reach the Great Barrier Reef to forage, a journey taking more than a month.

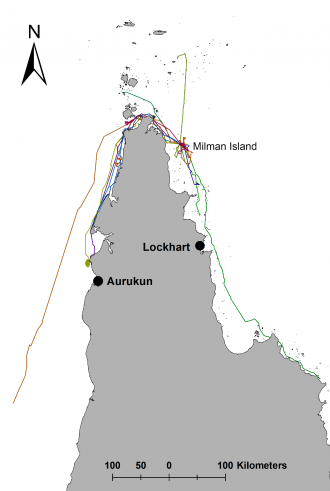

But hawksbills satellite-tagged in northeast Queensland’s Milman Island stayed in Australian waters, mostly swimming north to forage in Torres Strait and around to western Cape York, according to a separate Queensland-focused study. Both papers on the critically endangered species were recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science.

The research showed the importance of safeguarding hawksbill migratory routes and foraging habitats in north-east Australia, said lead author of both papers, Christine Madden Hof, a PhD candidate at the University of Sunshine Coast and leader of WWF’s Global Marine Turtle Conservation programme.

“That’s why conservationists applauded the Queensland and Australian governments’ recent commitment to phase out commercial gill nets in the Great Barrier Reef,” Ms Madden Hof she said.

“Significant numbers of hawksbills either nest and permanently live in Queensland or travel long distances to forage here. So improved protection in north east Australia and the reefs surrounding Cape York is critical to saving this species," she said.

“Not just for the severely declining Milman Island population, but for hawksbill populations across the entire “It is critical not just for the severely declining Milman Island population, but for hawksbill populations across the entire western Pacific.

“Following on from the Great Barrier Reef gill net phase out, we’re keen to work with the Queensland government to implement net-free areas and support greater Indigenous or marine protected areas in western Cape York.

“It’s clear from the satellite tracking hawksbills are heading there and our modelling shows it can be a dangerous place for a turtle.”

Queensland study assesses migration patterns and threats

The Queensland study assessed the mortality risk to hawksbills. In western Cape York, where there is currently little to no protection, in large areas that risk was rated high to very high.

Threats include fishing nets and ghost gear, direct harvest, and increasing sand temperatures due to climate change.

Simon Miller, a co-author of the Queensland research and Great Barrier Reef fisheries expert at the Australian Marine Conservation Society said the findings demonstrated why gill nets had to be removed from the Great Barrier Reef and why new net-free areas were urgently needed in the western Cape.

“There is also a clear need for greater independent scrutiny of commercial fishing in hawksbill home ranges to give us an accurate picture of what is being caught,” Miller said.

Milman Island is the main nesting beach for what used to be a globally significant population of genetically distinct hawksbills known as the northeast Queensland stock.

A recent assessment, co-authored by Ms Madden Hof, revealed an alarming 58 percent decline over the last 28 years. It also predicts this population may be functionally extinct by 2032 if the current trajectory continues. Scientists fear a similar decline could also be occurring across the larger southwestern Pacific population.

Scientists fear a similar decline could also be occurring across the larger southwestern Pacific population.

PNG study on migration patterns and genetics

Genetic sampling of female hawksbills nesting in the Conflict Islands’ group and about 1,000km further north in Kavieng revealed they are significantly different from one another and all other known Asia-Pacific stocks.

With the addition of these two, nine genetically distinct populations have now been identified in the Asia-Pacific region, but researchers believe there are many more. They say each will need to be managed separately to ensure population recovery.

Co-author Hayley Versace, manager at Conflict Islands Conservation Initiative said the Islands were one of the most important sites in PNG for hawksbills, shared across vast migratory routes, with Australia and other Pacific nations.

“We need to continue to support local communities to collectively manage this resource for future generations to come,” she said.

PNG has no legislation to protect hawksbills. But given the plight of the species that could change.

Vagi Rei, Manager Marine Division from the Conservation and Environment Protection Agency of Papua New Guinea, said sea turtle harvesting for shell, meat and eggs continued in PNG and the Torres Strait in Australia under the Torres Strait Treaty,with no legislative or regulated quota limits.

“This study has highlighted the need for greater national protection for hawksbills but given the migratory and foraging connectivity to eastern Cape York, stronger regional co-management and cooperation between the PNG and Australian Government is required,” he said.

Notes to Editor

This is the first time satellite tracking and genetic data from PNG hawksbill turtles has been published. All threats to the northeast Queensland hawksbill stock were assessed using a combination of a post-hatchling dispersal model, new satellite tracking of post-nesting migrations and a comprehensive review of threat-based data.

PNG Genetic data was shared to ShellBank (www.shellbankproject.org) a marine turtle traceability toolkit and global database of marine turtle DNA. Expanding the genetic baseline for marine turtles globally is a key project led by WWF in partnership with NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Centre, Australian Museum, and TRACE Wildlife Forensics Network.

Hawksbills tagged in the Conflict Islands migrated for between 24 to 65 days at an average swimming speed of 1.67 km per hour. Their mean migration distance was 1241 km, much greater than distances revealed in most studies: Hawaii (218km), Eastern Pacific (113km), Northern Territory (349km), US Virgin Island (67km). Only the Solomon Islands (2028km) was greater.

Multimedia

Australia; QLD

Australia; QLD