News release

From:

From the four authors of this paper:

Christine Chesley (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University), Samer Naif (School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology), Kerry Key (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University) and Dan Bassett (GNS Science):

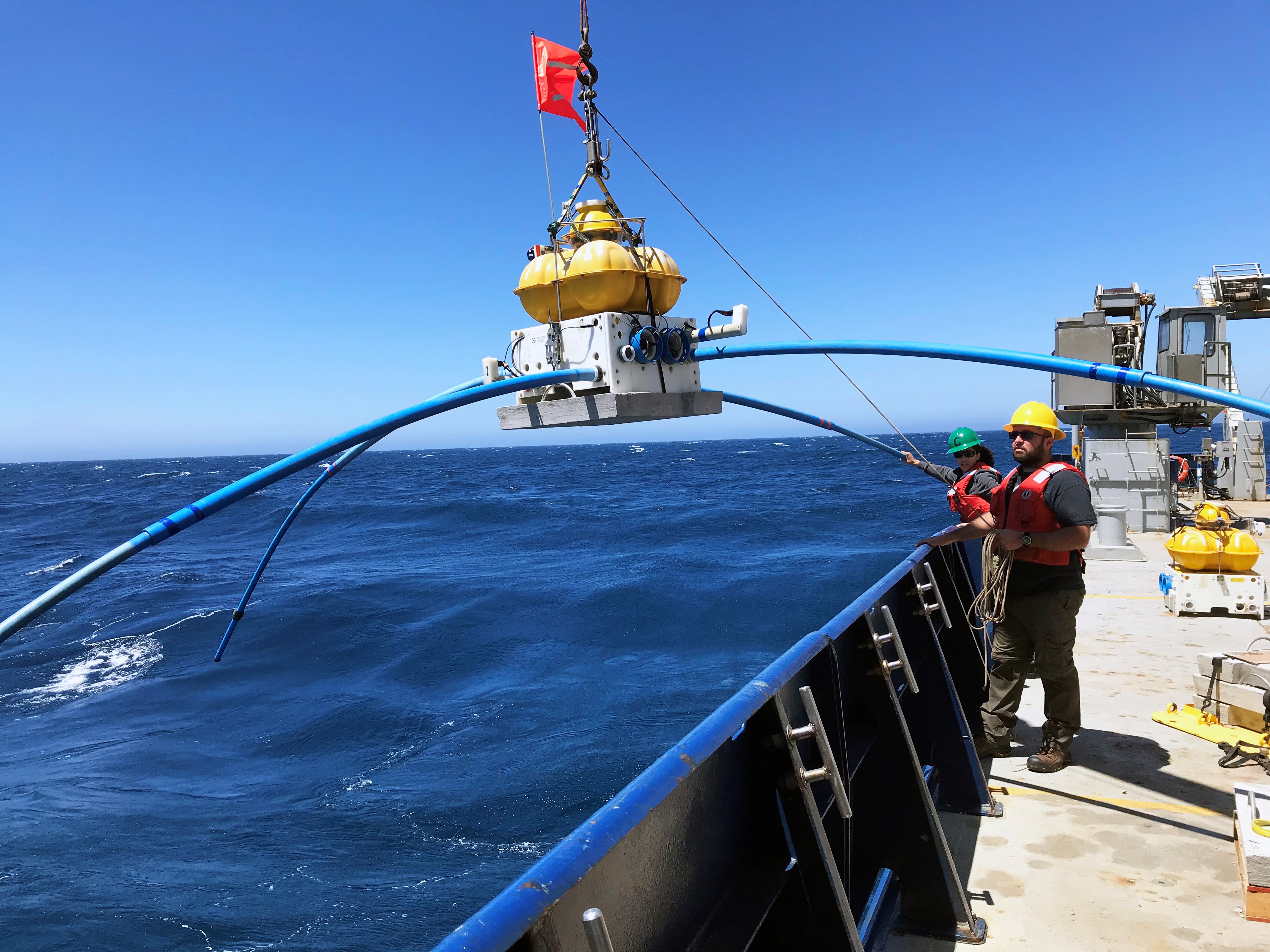

"Our article describes the novel application of a state of the art tool to help us better understand dynamic processes that may contribute to earthquakes and tsunamis. The tool - marine electromagnetic methods - essentially enables us to take an MRI of the Earth at different locations on the seafloor so that we can analyse a property called electrical conductivity at depths we would not otherwise be able to access. Electrical conductivity tells us how well a rock or other material can transmit an electric current. Because seawater is conductive, electromagnetic methods are highly sensitive to the presence of seawater trapped in the pore spaces of rocks. Natural variations in Earth’s magnetic field provide one source for this method and we also towed an instrument that can generate an electromagnetic source just above the seafloor. Other instruments that we place on the seafloor allow us to record how these electromagnetic waves travel through the underlying rock of the seafloor. With these data, we are able to create a geophysical picture of the material beneath the seafloor.

"In applying this technique offshore the North Island of New Zealand, we discovered that mountains on the seafloor (seamounts) can store a lot of water that they transport back down into the Earth at subduction zones. It is generally thought that fluids play a role in modulating different types of earthquakes, and in this particular region there are many “silent earthquakes” occurring that don’t shake the ground like San Andreas type events would. That doesn’t mean these slow motion earthquakes can’t contribute to hazard--in some cases they can still trigger tsunamis. It turns out there are a number of large seamounts on the seafloor in this region, so part of the major finding of our paper was that these seamounts might be locally supplying the subduction zone with water that could lead to conditions that favour silent earthquakes.

"We also used our imaging method to paint an electrical picture of what’s going on a bit closer to shore in the forearc, where the subduction zone begins. In that section of our study area, we see a few very conductive features above a seamount that is subducting as we speak. This suggests that the subducting seamount that is descending back into the Earth has damaged the plate above it. The high conductivity in the broken pockets of rock indicate that fluids were transferred into these damage zones, possibly from the subducting seamount or from subducting sediments. A startling finding was that a class of tiny, repeating earthquakes associated with a recent silent earthquake clusters around the damage zone. That realization seems to point to a link, if still an enigmatic one, between silent earthquakes and subducting seamounts, which will undoubtedly be a relevant consideration in natural hazard assessments for coastal regions."

New Zealand

New Zealand