News release

From:

Possible evidence for human transmission of Alzheimer’s pathology

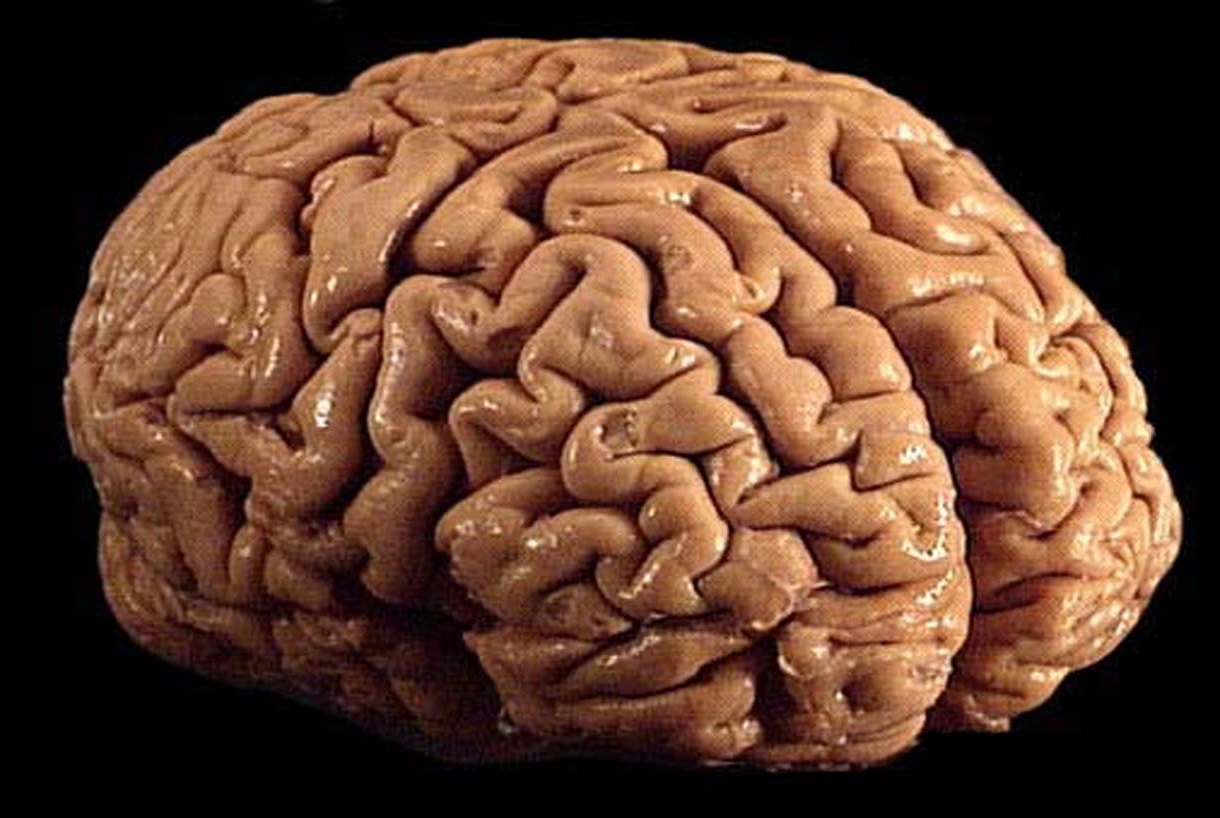

Amyloid beta pathology in the grey matter and blood vessel walls characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and the related cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is observed in the brains of deceased patients who acquired Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) following treatment with prion-contaminated human growth hormone. Although there is no evidence that human prion disease, AD or CAA is contagious (spread from person to person by direct contact), the study of eight patients, published in this week’s Nature, suggests that amyloid beta (the peptides that form the main components of the amyloid plaques found in the brains of patients with AD) may potentially be transmissible via certain medical procedures.

Human transmission of prion disease has occurred as a result of various medical procedures (iatrogenic transmission), with incubation periods that can exceed five decades. One such iatrogenic route of transmission was via the treatment in the UK of 1,848 persons of short stature with human growth hormone (HGH) extracted from cadaver-sourced pituitary glands, some of which were inadvertently prion-contaminated. The treatments began in 1958 and ceased in 1985 following reports of CJD among recipients. By the year 2000, 38 of the patients had developed CJD. As of 2012, 450 cases of iatrogenic CJD have been identified in countries worldwide after treatment with cadaver-derived HGH and, to a lesser extent, other medical procedures, including transplant and neurosurgery.

John Collinge, Sebastian Brandner and colleagues conducted autopsy studies, including extensive brain tissue sampling, of eight UK patients aged 36–51 with iatrogenic CJD. The authors show that in addition to prion disease in all eight brains sampled, six exhibited some degree of amyloid beta pathology (four widespread) and four of these had some degree of CAA. Such pathology is rare in this age range and none of the patients were found to have mutations associated with early-onset AD. There were no signs of the tau protein pathology characteristic of AD, but the full neuropathology of AD could potentially have developed had the patients lived longer. The authors examined a cohort of 116 patients with other prion diseases and found no evidence of amyloid beta pathology in the brains of patients of similar age range or a decade older who did not receive HGH treatment.

The study suggests that healthy individuals exposed to cadaver-derived HGH may be at risk of iatrogenic AD and CAA, as well as iatrogenic CJD, as they age. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms involved, but it seems likely that, as well as prions, the pituitary glands used to make the HGH contained the amyloid beta seeds that caused the amyloid beta pathology observed. The results should prompt investigation of whether other known iatrogenic routes of prion transmission, including surgical instrument use and blood transfusion, could also be relevant to the transmission of AD, CAA and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Professor Perminder Sachdev is Professor of Neuropsychiatry at UNSW

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), like many other degenerative diseases of the brain, is characterised by the deposition of abnormal aggregates of proteins in the brain, in particular two proteins, viz. β-amyloid (Aβ) which forms plaques and p-tau which forms the neurofibrillary tangles. For some time, scientists have believed that if these abnormal proteins are seeded in the brain, they tend to spread, thereby acting as ‘infectious’ particles. This has been called the ‘prion’ hypothesis, which is well recognised in another neurodegenerative condition, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). CJD, a rare but fatal disease, is known to be transmitted between individuals. Two well-known mechanisms are the consumption of beef from affected cattle (mad cow disease) and the use of pooled human growth hormone (c-hGH) tissue from cadavers used until 1985 to treat growth deficiency in children.

Until recently, there was no evidence that person to person transmission of AD could occur in humans. A recent paper in the journal Nature has provided evidence to support this possibility. The investigators from London examined the brains of 8 individuals who died from CJD, having earlier received the c-hGH. Surprisingly, 4 brains had extensive Aβ deposits and another 2 had fewer lesions. These people were in their 30s and 40s, and normal individuals, or those who die of CJD at this age unrelated toc- hGH from cadavers, do not have such Aβ deposits in their brain, suggesting that along with the prions for CJD, the c-hGH was possibly also contaminated with Aβwhich got seeded in the brains of the recipients. The deposits were greater in the blood vessels rather than in the brain substance, which is not surprising as the seeds arguably travelled to the brain through the blood.

The individuals who were part of this study died of CJD, and not AD, but we cannot know that if they would have eventually developed AD. Until 1985, about 30,000 children worldwide were treated with c-hGH, and in 2012, it was estimated that 226 had developed CJD. A study in 2008 did not suggest that this group was more likely to develop AD, but we cannot rule out the possibility that the incubation period for AD is much longer. These individuals should, therefore, be followed up, and there may be merit in imaging their brains for amyloid deposits.

At present there is no indication that AD can be transmitted between individuals under ordinary circumstances, e.g. through blood products. CJD is known to be transmitted through pituitary hormones, dura mater (brain covering) grafts, corneal transplants, contaminated neurosurgical instruments, and blood products from affected cattle. This report will excite new research on the conditions under which human transmission of AD could occur. There is no reason to be alarmed at this stage. Prion sterilization procedures should be applied to all neurosurgical instruments, and of course cadaveric pituitary hormones are no longer used. There is in fact hope that this research will lead to mechanisms by which the propagation of AD pathology can be halted, and new treatments emerge.

Dr Ian Musgrave is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine, School of Medicine Sciences, within the Discipline of Pharmacology at the University of Adelaide.

Proteins are long chains of amino acids. Most proteins need to fold up into a specific shape to work, sometimes this folding goes wrong and the misfolded proteins can cause disease. Examples include the beta amyloid protein - thought to play a central role in Alzheimer’s disease - and prions.

Prions also are able to be “infectious” in that the misfolded, toxic prion protein can induce normal prion proteins to misfold into the toxic form. “Infectious” prion diseases include Kuru and Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, where people were able to contract the prion disease by eating brain and spinal cord containing the misfolded prion protein, leading to the spread of the toxic misfolded proteins in the brains of those that consumed them, leading to neurodegeneration. It has long been suspected that the misfolded beta amyloid found in Alzheimer’s disease also has prion like properties. Misfolded beta Amyloid can convert soluble beta amyloid into toxic aggregates in test-tube experiments, and if you inject high enough concentrations into the brains of mice. However, there was no evidence that this could occur in people.

This new paper shows that some people who were injected with human growth hormone sources from human brains, and contaminated with the Creutzfeldt-Jakob prion, developed deposits of misfolded beta Amyloid in their brains.

It is likely that the beta amyloid deposits were developed from injected misfolded beta amyloid, rather than the Creutzfeldt-Jakob prion inducing the production of misfolded beta Amyloid. This suggests that once misfolded beta Amyloid is produced in the process of developing Alzheimer’s disease, it can accelerate its own production. But Alzheimer’s is not infectious in the common sense - beta Amyloid has very weak prion-like activity, you would be unlikely to develop Alzheimer’s disease even if you ate the brain of someone with Alzheimer’s.

Dr Lyndsey Collins-Praino, is a Lecturer in the School of Medicine at the University of Adelaide

Amyloid-beta (Aβ) is the major pathological marker of Alzheimer’s disease. In their paper, Jaunmuktane and colleagues demonstrate both brain and blood vessel amyloid-beta (Aβ) pathology in six out of eight patients who died from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), developed from receiving treatment with prion-contaminated human growth hormone derived from the pituitary glands of cadavers (c-hGH).

Such Aβ pathology is very rare in individuals as young as the subjects in the current study, none of whom showed any known genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Patients who died from other prion diseases did not show this Aβ-pathology, suggesting that Aβ-seeds had been derived along with c-hGH from the pituitary glands of the cadavers.

These findings raise the interesting possibility that Aβ may be transmissible between humans under certain rare circumstances. It is important to keep in mind that these findings are preliminary. There is no current evidence that Aβ pathology is transmissible between humans under ordinary circumstances. Future studies will need to investigate whether the original c-hGH extracts contain Aβ-seeds, and to rule out whether CJD can lead to Alzheimer’s pathology. Additionally, subjects who underwent c-hGH treatment should be carefully monitored to see if they are at increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Professor Ralph Martins is Director of the Centre of Excellence for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and Care and the Foundation Chair of Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease at Edith Cowan University in WA.

A major diagnostic feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the build-up in the brain of a small protein called amyloid beta. This protein is typically found outside neurons of the brain and within the blood vessels of the brain. In this paper, John Collinge, Sebastian Bradner and colleagues report that the brains of deceased patients who acquired Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) following treatment with prion-contaminated human growth hormone also show evidence of AD.

There is strong evidence in the published scientific literature that a number of people of short stature injected with prion-contaminated human growth hormone obtained from cadavers do develop CJD but the suggestion by these authors that AD is transmitted by human transmission is a new observation. They provide evidence that the brains of eight people who died of CJD at a relatively young age (31 to 50 years of age) showed the deposition of beta amyloid in their brain. They argue that their finding supports human transmission because the eight people are too young to exhibit AD brain pathology and do not have any of the genetic forms of AD that are known to cause early onset AD. Furthermore they do not see Amyloid beta in the brains of 116 people who died of other prion diseases.

While the findings of this study might imply that AD is transmitted following treatment of prion-contaminated human growth hormone it should be recognized that this study is a relatively small observational study and thus does not show cause and effect. These findings do not allow for a definite conclusion that there is human transmission in AD. Further work is required to determine the significance of these findings and to explore other explanations such as whether the AD pathology is a secondary effect of prion-contaminated human growth hormone treatment i.e. inflammation.

This interesting study needs to be followed up to determine whether amyloid beta behaves like prions to replicate itself, but, irrespective of this outcome, it should be noted that neither CJD nor AD is contagious.

Professor Bob Williamson is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow of the University of Melbourne and Scientific Director of the Yulgilbar Alzheimer’s Research Program.

These data are interesting, although the study only looked at the brains of eight individuals. All of those studied received injections of human brain-derived growth hormone, which caused their death from brain degeneration, and in half the cases the patients developed deposits similar to those seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Today no one would inject brain extracts from one person to another, although when this was done forty years ago it was an important medical intervention.”

“Professor Collinge is a world expert on this extremely rare form of brain degeneration in humans, prion disease, which is known to be transmissible. Although there may be exceptional situations where dementia, like prion disease, may move from one person to another (as when brain material is injected), the real significance of this research is that the mechanism underlying Alzheimer’s disease may have more in common with better-understood prion disease than previously thought. This might let researchers try to block aggregation of the proteins amyloid and tau, which many think cause Alzheimer’s disease, using techniques that are already being tested for prion disease.

Perhaps most exciting, there are recent promising reports of new antibody and ultrasound approaches to removing aggregates of amyloid from the brain, and other research that can identify people at high risk of Alzheimer’s disease long before symptoms appear. No single approach is likely to succeed, but if these can be put together in combination with blocking aggregation, the objective of delaying the onset of dementia by years or decades might be achieved.

Dr Maurice Curtis, Deputy Director, Neurological Foundation Human Brain Bank, and Associate Professor, University of Auckland

This is very interesting work that demonstrates higher than usual amyloid pathology in the brains of 4 out of 8 patients who had CJD as a result of receiving growth hormones earlier in life. The importance of this work is in raising the possibility that amyloid pathology might be seeded in the brain as opposed to being endogenously produced in the brain.

This is not the first time the concept of transmissibility has been raised but usually the context relates to inhaling, ingesting or smelling a toxin that then begins the process of amyloid accumulation. To date both transmissibility and the toxin argument are unproven but remain tantalising hypotheses.

The current study has been performed on a very small number of patients, and patients who received the growth hormones but did not get Creutzfeld Jacob disease do not appear to have been tested for amyloid deposition…this is a serious limitation in this study.

The size of the study and the lack of direct evidence that the growth hormone injection led to amyloid deposition is a limiting factor in this study (no smoking gun). With that said, until we know exactly how degenerative brain diseases begin we must not exclude any possibilities.

The work we are doing in my laboratory at the Centre for Brain Research is directly related to understanding the route of entry and early origins of degenerative diseases and so I can see the value in pursuing the line of research this group has taken.

Dr Claire Shepherd is a Senior Researcher at NeuRA and Conjoint Lecturer in Pathology, UNSW.

“The findings are certainly interesting and warrant further investigation. Amyloid-beta protein deposition is an unusual finding in the brains of young individuals who do not have a known genetic predisposition to the disease. The first question to answer is whether transmission through contaminated injections is in fact possible and can lead to full blown Alzheimer’s disease (tau, amyloid-beta deposition and cell loss).

The incubation period was extensive and progression of the disease would certainly be expected during this time if the normal disease process was underway. The diffuse amyloid-beta deposits seen would certainly not be sufficient to cause clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Whilst further research is clearly warranted, it is premature to suggest that medical procedures involving implements that had previously been used on individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease could cause transmission of the disease.”

Dr Bryce Vissel is a Professor in the School of Clinical Medicine at UNSW and Director of the Centre for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at St Vincent's Hospital Sydney

This extraordinary study by John Collinge, Sebastian Brandner and colleagues suggests that healthy individuals exposed to cadaver-derived Human growth hormone may be at risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and the related cerebral amyloid angiopathy as well as iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease as they age. This study is extraordinary as it suggests that pituitary glands of humans used to make the human growth hormone contained seeds that caused the amyloid beta pathology observed. This matters enormously as it raises the possibility that other routes of transmission, including surgical instrument use and blood transfusion, could be relevant to the transmission of Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy and other neurodegenerative diseases. There however continues to be great controversy around the mechanisms that cause Alzheimer’s disease and so the current study will be yet another one that adds to the challenging and important ongoing debate.

Professor Colin Masters is Senior Deputy Director of The Florey Institute and Laureate Professor at The University of Melbourne

"The numbers of cases are small (eight), but four of these did have significant Abeta deposition, so it comes down to an assessment of whether this is more than would be expected in an aged-matched population (ages 36-51). This age span is exactly at the transition period between normality and the earliest phases of preclinical sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. We were the first to explore this age group in 1988*. In our sample we did not find anyone positive under the age of 50 years, but only 20 cases were looked at. In the current study, the authors used a special technique (formic acid prion inactivation which incidentally retrieves antigens normally invisible) which may have enhanced their ability to see the Abeta plaques in this young age group.

So we need to be very careful over the interpretation of these findings. Most importantly, there are many recipients of pituitary products from the past (approximately 2000 people in Australia received the product and 4 of them developed CJD), who will be concerned now whether they have an increased risk of developing AD. Our message to these recipients is that much more work is required to settle this issue. Currently, Prof Steve Collins of the Australian National CJD Case Registry is reviewing all the files of recipients who have died over the last 30 years. This work is ongoing and we will get results in the near future."

International

International