Media release

From:

Peer-reviewed Observational study People

Study finds distinct biological ages across individuals’ various organs and systems

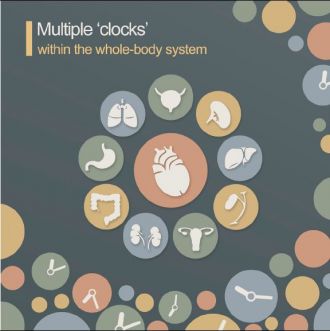

It’s common to say that someone looks either younger or older than their chronological age, but aging is more than skin deep. Our various organs and systems may have different ages, at least from a biological perspective. In a study published March 8 in the journal Cell Reports, an international team of investigators used biomarkers, statistical modeling, and other techniques to develop tools for measuring the biological ages of various organ systems. Based on their findings, the researchers report that there are multiple “clocks” within the body that vary widely based on factors including genetics and lifestyle in each individual.

“Our study used approaches that can help improve our understanding of aging and—more importantly—could be used some day in real healthcare practice,” says co-corresponding author Xun Xu of the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) and China National GeneBank (CNGB) in Shenzhen, China. “We used biomarkers that could be identified from blood and stool samples plus some measurements from a routine body checkup.”

The concept of evaluating people’s biological aging rates has been around since the 1970s, but earlier studies were focused either on developing methods for estimating one centralized aging index or studying the molecular aging biomarkers using tissues and cell cultures outside the body.

“There has been a lack of practical applications in a population-based sample for precisely estimating the aging rates of live people’s organs and systems,” says co-corresponding author Xiuqing Zhang, also of BGI and CNGB. “So we decided to design one.”

To do this research, the investigators recruited 4,066 volunteers living in the Shenzhen area to supply blood and stool samples and facial skin images and to undergo physical fitness examinations. The volunteers were between the ages of 20 and 45 years; 52% were female and 48% were male. “Most human aging studies have been conducted on older populations and in cohorts with a high incidence of chronic diseases,” says co-corresponding author Brian Kennedy of the National University of Singapore. “Because the aging process in young healthy adults is largely unknown and some studies have suggested that age-related changes could be detected in people as young as their 20s, we decided to focus on this age range.”

In total, 403 features were measured, including 74 metabolomic features, 34 clinical biochemistry features, 36 immune repertoire features, 15 body composition features, 8 physical fitness features, 10 electroencephalography features, 16 facial skin features, and 210 gut microbiome features. These features were then classified into nine categories, including cardiovascular-related, renal-related, liver-related, sex hormone, facial skin, nutrition/metabolism, immune-related, physical fitness-related, and gut microbiome features.

Because of the difference in sex-specific effects, the groups were divided into male and female. The investigators then developed an aging-rate index that could be used to correlate different bodily systems with each other. Based on their findings, they classified the volunteers either as aging faster or aging slower than their chronological age.

Overall, they discovered that biological ages of different organs and systems had diverse correlations, and not all were expected. Although healthy weight and high physical fitness levels were expected to have a positive impact, the investigators were surprised by other findings. For example, having a more diverse gut microbiota indicated a younger gut while at the same time having a negative impact on the aging of the kidneys, possibly because the diversity of species causes the kidneys to do more work.

The investigators also used their approach to look at other datasets, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, which includes data on more than 2,000 centenarians with matched middle-aged controls. In addition, they looked at single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to determine whether differences could be explained by genetic factors. There, they did find certain pathways that could be associated with aging rates.

The researchers plan to regularly follow up with the study participants to track the development of aging and validate their findings. Future studies will use additional approaches for classifying features of aging and studying the interactions between organ systems.

They also plan to use single-cell technology to look at programmed aging in more detail. “It’s important to capture the cell-to-cell variation in an aging individual, as this will tell us important information about the heterogeneity within cell types and tissues and provide important insights into aging mechanisms,” says co-corresponding author Claudio Franceschi of Lobachevsky State University in Russia.

Multimedia

International

International