News release

From:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

New study on the Antarctic Peninsula shows that the choices we make in the next decade will determine Antarctica’s fate for centuries

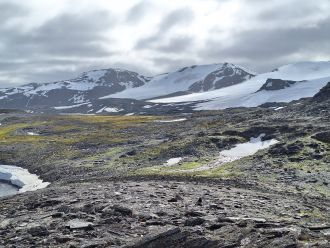

Antarctica’s pale expanses of ice keep water locked up and reflect heat from the planet — but the climate crisis is putting these safeguards at increasing risk. Antarctica is warming much faster than the global average, which could destroy its ecosystems and put other parts of the planet at risk by driving sea level rise and damaging food chains. Scientists modelling possible climate crisis outcomes for the Antarctica Peninsula show just how high the stakes are if we don’t act now.

The climate crisis is warming Antarctica fast, with potentially disastrous consequences. Now scientists have modelled the best- and worst-case scenarios for climate change in Antarctica, demonstrating just how high the stakes are — but also how much harm can still be prevented.

“The Antarctic Peninsula is a special place,” said Prof Bethan Davies of Newcastle University, lead author of the article in Frontiers in Environmental Science and UK national nominee for the 2026 Frontiers Planet Prize. “Its future depends on the choices that we make today. Under a low emissions future, we can avoid the most important and detrimental impacts. However, under a higher emissions scenario, we risk the loss of sea ice, ice shelves, glaciers, and iconic species such as penguins.

“Though Antarctica is far away, changes here will impact the rest of the world through changes in sea level, oceanic and atmospheric connections and circulation changes. Changes in the Antarctic do not stay in the Antarctic.”

A race against time

The scientists focused on the Antarctic Peninsula, a center for research, tourism, and fishing which is both very well-studied — which helps us track the effects of global warming on its ecosystem — and very vulnerable to anthropogenic changes.

“I originally spent my first period in Antarctica as a 'winterer' on the Signy Station in the South Orkney Islands, from November 1989 to April 1991,” said Prof Peter Convey of the British Antarctic Survey, co-author. “For a casual visitor, the first impression is still inevitably that the region is ice-dominated. However, to those of us that have the privilege to go back multiple times, there are very clear changes over time.”

The scientists used scenarios which estimate future emissions to model outcomes for the Antarctic Peninsula: low emissions (1.8°C temperature rise compared to preindustrial levels by 2100), medium-high emissions (3.6°C), and very high emissions (4.4°C). They looked at eight different aspects of the Peninsula’s environment affected by climate change: marine and terrestrial ecosystems, land and sea ice, ice shelves, the Southern Ocean, the atmosphere, and extreme events like heatwaves.

“In 2019, we demonstrated how the Antarctic Peninsula would be affected by the 1.5°C climate scenario,” said Prof Martin Siegert of the University of Exeter, co-author. “Now, in 2026, we share what exceeding 1.5°C looks like for the Antarctic Peninsula, which is a frightening prospect.”

High stakes

In higher emissions scenarios, the Southern Ocean will get hotter faster. Warmer ocean waters will erode ice on land and at sea. The higher temperatures get, the more likely ice shelves are to collapse, driving sea level rise.

Under the highest emissions scenario, sea ice coverage could fall by 20%, devastating species that rely on it — such as krill, an important prey for whales and penguins — and amplifying ocean warming worldwide. Higher ocean warming would also stress ecosystems and contribute to extreme weather.

Although it’s difficult to predict how these environmental changes would combine to affect animals, the scientists expect that under very high emissions scenarios, many species will move south to escape higher temperatures. Warm-blooded predators may cope with temperature changes, but if their prey can’t, they will starve.

An uncertain world

Researchers aren’t safe from the consequences of climate change either: damage to infrastructure is making it more dangerous to carry out research, so it’s harder to collect the data needed to forecast the future effects of climate change. Although numerical models simplify reality, more data makes them more accurate. However, the scientists emphasize that we must act now to avoid the worst-case scenarios.

“At the moment, we’re on track for a medium to medium-high emissions future,” said Davies. “A lower emissions scenario would mean that although the current trends of ice loss and extreme events would continue, they would be much more muted than under a higher scenario. Winter sea ice would be only slightly smaller than today, and sea level contributions from the Peninsula would be limited to a few millimeters. Most of the glaciers would be recognizable and we would retain the supporting ice shelves.

“What concerns me most about the higher emissions scenario is just how permanent the changes could be. These changes would be irreversible on any human timescale. It would be very hard to regrow the glaciers and bring back the wildlife that makes Antarctica special. If we don’t make changes now, our great-grandchildren will have to live with the consequences.”

Multimedia

International

International