Media release

From:

‘Built for cutting flesh, not resisting acidity’: sharks may be losing deadly teeth to ocean acidification

Scientists found that some of the oceans’ fiercest hunters could be losing their bite: As oceans become more acidic, sharks’ teeth may become structurally weaker and more prone to break

A leading cause of a rising pH value in the world’s oceans is human CO2 emission. As more CO2 is released into the atmosphere and absorbed by the oceans, the water becomes more acidic. This poses problems for many organisms – including sharks, a new study showed. Scientists incubated shark teeth in water with pH levels that reflect the current ocean pH, and in water with a pH value that oceans are predicted to reach by 2300. In the more acidic water of the simulated scenario, shark teeth, including roots and crowns, were significantly more damaged. This shows how global changes reach all the way to the microstructure of sharks’ teeth, the researchers said.

Sharks can famously replace their teeth, with new ones always growing as they’re using up the current set. As sharks rely on their teeth to catch prey, this is vital to the survival of one of the oceans’ top predators.

But the ability to regrow teeth might not be enough to ensure they can withstand the pressures of a warming world where oceans are getting more acidic, new research has found. Researchers in Germany examined sharks’ teeth under different ocean acidification scenarios and showed that more acidic oceans lead to more brittle and weaker teeth.

“Shark teeth, despite being composed of highly mineralized phosphates, are still vulnerable to corrosion under future ocean acidification scenarios,” said first author of the Frontiers in Marine Science article, Maximilian Baum, a biologist at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU). “They are high developed weapons built for cutting flesh, not resisting ocean acid. Our results show just how vulnerable even nature’s sharpest weapons can be.”

Damage from root to crown

Ocean acidification is a process during which the ocean’s pH value keeps decreasing, resulting in more acidic water. It is mostly driven by the release of human-generated CO2. Currently, the average pH of the world’s oceans is 8.1. In 2300, it is expected to drop to 7.3, making it almost 10 times more acidic than it currently is.

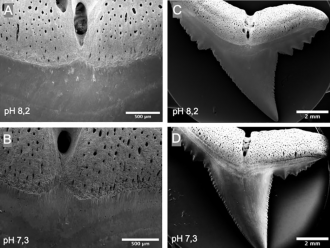

For their study, the researchers used these two pH values to examine the effects of more and less acidic water on the teeth of Blacktip reef sharks. Divers collected more than 600 discarded teeth from an aquarium housing the sharks. 16 teeth – those that were completely intact and undamaged – were used for the pH experiment, while 36 more teeth were used to measure before and after circumference. The teeth were incubated for eight weeks in separate 20-liter tanks. “This study began as a bachelor’s project and grew into a peer-reviewed publication. It’s a great example of the potential of student research,” said the study’s senior author, Prof Sebastian Fraune, who heads the Zoology and Organismic Interactions Institute at HHU. “Curiosity and initiative can spark real scientific discovery.”

Compared to the teeth incubated at 8.1 pH, the teeth exposed to more acidic water were significantly more damaged. “We observed visible surface damage such as cracks and holes, increased root corrosion, and structural degradation,” said Fraune. Tooth circumference was also greater at higher pH levels. Teeth, however, did not actually grow, but the surface structure became more irregular, resulting in it appearing larger on 2D images. While an altered tooth surface may improve cutting efficiency, it potentially also makes teeth structurally weaker and more prone to break.

Small damage, big effects

The study only looked at discarded teeth of non-living mineralized tissue, which means repair processes that may happen in living organisms could not be considered. “In living sharks, the situation may be more complex. They could potentially remineralize or replace damaged teeth faster, but the energy costs of this would be probably higher in acidified waters,” Fraune explained.

Blacktip reef sharks must swim with their mouths permanently open to be able to breathe, so teeth are constantly exposed to water. If the water is too acidic, the teeth automatically take damage, especially if acidification intensifies, the researchers said. “Even moderate drops in pH could affect more sensitive species with slow tooth replication circles or have cumulative impacts over time,” Baum pointed out. “Maintaining ocean pH near the current average of 8.1 could be critical for the physical integrity of predators’ tools.”

In addition, the study only focused on the chemical effects of ocean acidification on non-living tissue. Future studies should examine changes to teeth, their chemical structure, and mechanical resilience in live sharks, the researchers said. The study shows, however, that microscopic damage might be enough to pose a serious problem for animals depending on their teeth for survival. “It’s a reminder that climate change impacts cascade through entire food webs and ecosystems,” Baum concluded.

Multimedia

International

International