News release

From:

Whales, dolphins and other marine mammals are highly social, but those social ties can also help diseases spread through populations of rare or threatened species.

New research reveals why understanding these social networks is critical for predicting and managing disease outbreaks in oceans already under siege with pressures from climate change, pollution and human activities.

In a new global study, marine mammal experts from Flinders University and the US warn of the potential of pandemics in marine environments, with some species more vulnerable than others.

Flinders University Associate Professor Guido J Parra says infectious disease transmission in marine mammals is understudied, posing a particular risk for more than one-quarter of the species classified as threatened.

“Disease is one of the leading causes of mortality in marine vertebrates, along with fisheries interactions, pollution, habitat degradation and climate change,” says Associate Professor Parra from the Cetacean Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution Lab (CEBEL) at Flinders University.

“These stressors tend to weaken immune systems and make animals more vulnerable to infection.

“Like people, marine mammals have social networks, and diseases move through them. Understanding how these networks differ between species, and how some species interact with others, is essential for developing effective, targeted conservation strategies to manage disease risk.”

Caitlin Nicholls, PhD candidate with the CEBEL research group at Flinders’ College of Science and Engineering, says dolphins, whales and seals are highly social animals. Many live in groups, form long-term relationships with preferred companions, while others move between groups in fluid, ever-changing social networks.

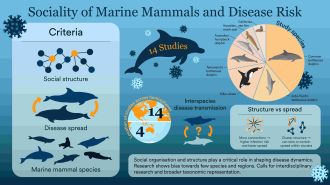

“Unlike on land, scientists cannot easily observe every interaction, isolate sick individuals, or intervene early when disease begins to spread,” says Ms Nicholls, lead author in a new article in Mammal Review, which used historic research spanning decades to model different species behaviours to map social connections and patterns.

“One of the clearest findings was that highly connected individuals often play an outsized role in disease spread. These animals, sometimes called ‘super spreaders,’ interact with many others and can rapidly pass infections through a population.

“In dolphin communities, for example, animals with stronger or more frequent social ties are more likely to be associated with disease.

“And while bottlenose dolphins are among the most studied species – particularly in Australia and North America – many threatened species and other regions remain poorly studied, limiting our ability to assess and manage disease risk.”

Researchers say the findings have important implications for how we monitor and manage wildlife health.

Marine mammals are difficult, and often impossible, to treat once disease is widespread.

“Prevention, early detection and informed management will be critical, particularly for the most vulnerable populations before an outbreak makes animals sick,” adds Associate Professor Parra.

“Understanding social relationships can help identify which individuals or populations are most vulnerable before an outbreak occurs.

“In some cases, targeting monitoring efforts towards socially central animals could provide early warning signs of emerging disease. In others, protecting habitats that support stable social structures may help reduce transmission risk.

Photos: Courtesy CEBEL, Flinders University https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ci4t7PN7MNqHpRIax38UGl0cRCWfUy7E?usp=sharing

The new article, ‘Sociality of marine mammals and their vulnerability to the spread of infectious diseases: A systematic review’, (2026) by Caitlin R Nicholls, Mauricio Cantor (Marine Mammal Institute, Oregon State University), Luciana Möller and Guido J Parra has been published in Mammal Review DOI: 10.1111/mam.70020

https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.70020

Multimedia

Australia; International; SA

Australia; International; SA