News release

From:

Jellyfish and sea anemones sleep like humans

The sleep patterns of jellyfish and sea anemones share notable similarities with those of humans, according to research published in Nature Communications. The findings support the hypothesis that sleep evolved across a wide range of species to protect against DNA damage associated with wakefulness.

Sleep is a behaviour conserved across the animal kingdom. Among many benefits, it is known to play a key role in the reduction of DNA damage, particularly within the brain’s neurons . Neurons are thought to have evolved in basal metazoans, an early-emerging group of animals which would have been similar to the sea anemones and jellyfish alive today (members of the Cnidaria phylum). A sleep-like state has previously been documented in Cassiopea jellyfish, but the specific architecture of ‘sleep’ in these organisms and its role has remained unclear.

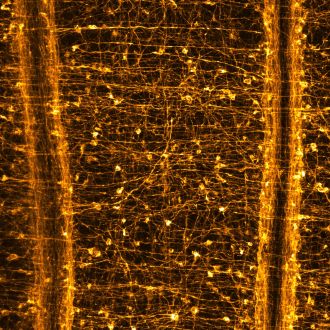

Lior Appelbaum, Raphaël Aguillon, and colleagues examined the sleeping patterns of jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda) in both the laboratory and their natural habitat, and sea anemones (Nematostella vectensis) solely observed in the laboratory. They found that both organisms sleep for roughly one third of the day, similar to humans. Jellyfish were observed to sleep through the night (with quick naps at around noon), whereas sea anemones slept mainly during the day. Further investigation into the mechanisms of these sleeping patterns found that sleep in jellyfish was controlled by changes in light and the homeostatic sleep drive (the body’s internal mechanism that tracks the need for sleep). For sea anemones, their sleep was regulated by their internal circadian clock and the homeostatic sleep drive.

The authors note that Cnidarians could provide an attractive model for studying the evolution of sleep in ancient animals. In both species, wakefulness and sleep deprivation were associated with increased neuronal DNA damage, whereas spontaneous or induced sleep was linked to a reduction in DNA damage. They also note that increases in DNA damage caused by external stressors resulted in the organisms sleeping more to compensate. These findings suggest that sleep may have evolved in these animals as a mechanism to reduce DNA damage and cellular stress associated with being awake.

Multimedia

International

International