Media release

From:

Few actions in nature inspire more fear or fascination than a snake bite.

Now, new research led by Monash University has revealed exactly how venomous snakes strike, using high-speed 3D cameras to capture the deadly precision of vipers, cobras, and rear-fanged snakes in unprecedented detail.

Published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, the study is the first to compare strike performance across 36 venomous species from around the world, filmed lunging at a warm, muscle-like gel that mimicked an animal’s flesh.

Lead author Dr Silke Cleuren, who completed the work as part of her PhD under Professor Alistair Evans in the School of Biological Sciences, said the team wanted to understand how each family of snakes evolved its own venom-delivery strategy.

“Venomous snakes have perfected the art of speed, accuracy and control,” Dr Cleuren said.

“Some vipers can reach their prey in less than one-tenth of a second, faster than the human eye can blink. But what’s really remarkable is how differently each group achieves the same deadly goal.”

To make the recordings, Dr Cleuren travelled to Venomworld, on the outskirts of Paris, where venom is collected from some of the world’s most dangerous snakes for medical and pharmaceutical use.

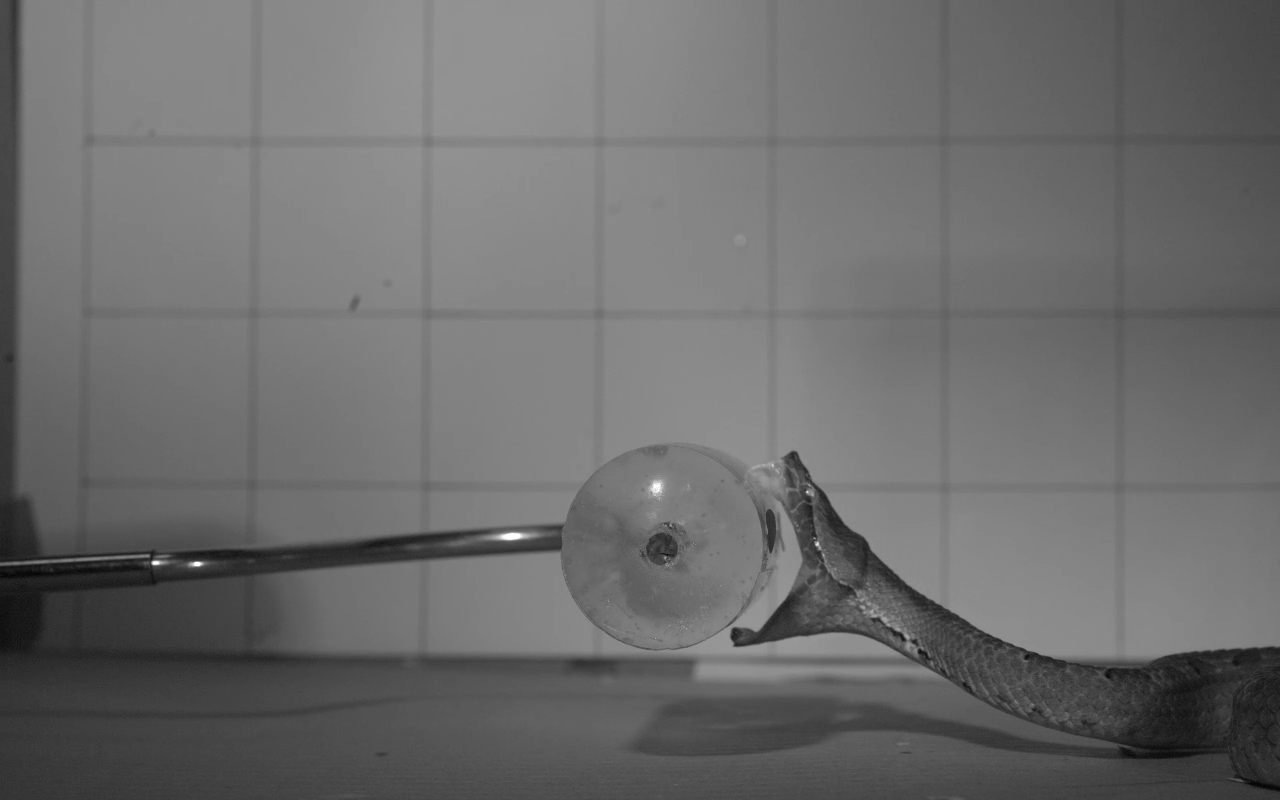

Working with Anthony Herrel from the Museum national d’Histoire naturelle (France) and Remi Ksas from Venomworld, the team enticed species including the western diamondback rattlesnake, West African carpet viper and rough-scaled death adder to strike at the heated gel while filming at 1,000 frames per second.

“Annoying a venomous snake with a piece of gel on a stick was an incredible adrenaline rush, I’ll admit I flinched a few times,” Dr Cleuren said. “But the footage we captured showed behaviour that’s impossible to see with the naked eye.”

The results showed that vipers strike within 100 milliseconds, then “walk” their fangs into position before injecting venom. Elapids, such as cobras and death adders, creep closer before striking and biting repeatedly to squeeze venom into their prey. Colubrids, whose fangs sit further back in their mouths, sweep their jaws from side to side to tear a gash that maximises venom delivery.

Professor Evans said the findings offer new insight into the evolution of one of nature’s most sophisticated weapons.

“Each snake family has evolved a strike perfectly tuned to its hunting style and prey,” he said. “It’s a brilliant example of how evolution shapes form and function in the natural world.”

Multimedia

Australia; VIC; TAS

Australia; VIC; TAS