News release

From:

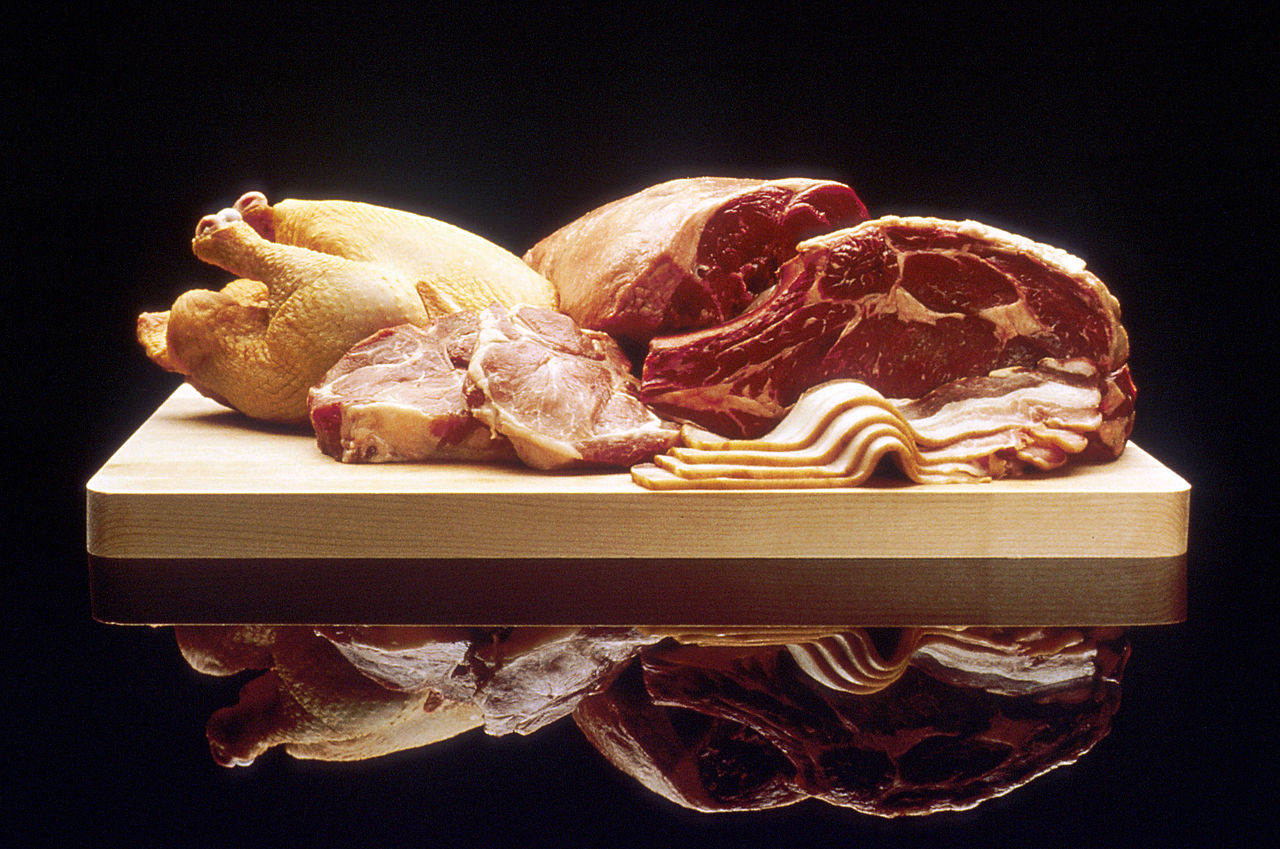

New guidelines: No need to reduce red or processed meat consumption for good health

A rigorous series of reviews of the evidence found little to no health benefits for reducing red or processed meat consumption

Based on a series of 5 high-quality systematic reviews of the relationship between meat consumption and health, a panel of experts recommends that most people can continue to consume red meat and processed meat at their average current consumption levels. Current estimates suggest that adults in North America and Europe consume red meat and processed meat about 3 to 4 times per week. The evidence reviews and recommendations are published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers from Dalhousie University and McMaster University in Canada, together with the Spanish (Iberoamerican) and Polish Cochrane Centers, performed four parallel systematic reviews that focused both on randomized controlled trials and observational studies addressing the possible impact of red meat and processed meat consumption on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes. A fifth systematic review addressed people’s health-related values and preferences on meat consumption. Based on those reviews, a panel comprised of fourteen members from seven countries voted on recommendations for red and processed meat consumption. Their conclusion that most adults should continue to eat their current levels of red and processed meat intake, is contrary to almost all other guidelines that exist.

Among 12 randomized trials enrolling about 54,000 individuals, the researchers did not find statistically significant or an important association between meat consumption and the risk of heart disease, diabetes, or cancer. Amongst cohort studies following millions of participants, the researchers did find a very small reduction in risk amongst those who consumed three fewer servings of red or processed meat per week. However, the association was very uncertain.

In addition to studying health effects, the authors also looked at people’s attitudes and health-related values surrounding eating red and processed meat. They found that people ate meat because they liked it or perceived it as healthy and would be reluctant to change their habits. The authors say they did not consider ethical or environmental reasons for abstaining from meat in their recommendations, however, these are valid and important concerns, though concerns that do not bear on individual health.

The researchers used the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) guideline development process, which includes rigorous systematic review methodology, and GRADE methods to rate the certainty of evidence for each outcome and to move from evidence to dietary recommendations to develop their guidelines. According to the authors, this is important because dietary guideline recommendations require close consideration of the certainty in the evidence, the magnitude of the potential harms and benefits, and explicit consideration of people’s values and preferences. Most nutritional recommendations are based on unreliable observational studies. However, the authors note that their recommendations are weak, based on low-certainty evidence. Of note, there may be reasons other than health concerns for reducing meat consumption.

The authors of an accompanying editorial from Indiana University School of Medicine say that while the new recommendations are bound to be controversial, they are based on the most comprehensive reviews of the evidence to date. Those that seek to dispute the NutriRECS findings will be hard-pressed finding appropriate evidence with which to build an argument.

Notes and media contacts: The meat recommendations include 5 reviews, a recommendation, and an editorial. For embargoed PDFs please contact Lauren Evans at laevans@acponline.org.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Catherine Saxelby is an accreditied Practicing Dietitian and an accredited Nutritionist

Studies from Australia show that men and boys eat too much meat and not enough veggies and they are resistant to the ‘don’t eat meat’ message.

They also show that women and girls are already at the recommended low levels of around 90 grams uncooked meat a day but it’s the men and boys who need to reduce – but not cut out completely.

You don’t need to trade down to sausages and mince. You can still enjoy meat but as part of a balanced nutritious meal that combines vegetables and grains but takes its flavour highlights from the protein.

I don’t believe one needs to go vegan or cut out meat the way many people now do. One can still enjoy the benefits of vegetables without swearing off all meat. It’s about reducing meat consumption, saying no to processed meats, and boosting consumption of vegetables.

Meat, chicken and fish offer valuable nutrients too and as a nation we are already short on iron, zinc, iodine, vitamin B12 and omega-3’s which come from these foods.

I am against processed meats such as salamis and bacon and view them as an early form of processing when there was no refrigeration.

Jim Mann, Professor of Medicine and Human Nutrition and co-director, Edgar Diabetes and Obesity Research Centre, University of Otago; Director, Healthier Lives National Science Challenge

In my opinion the 'weak recommendations' based on 'low certainty' evidence that adults 'continue current consumption of unprocessed red meat and processed meat' are potentially unhelpful and could be misleading.

The panel opted to consider personal preferences along with cancer and cardiovascular outcomes but not to take into account environmental and animal welfare issues when making their recommendations. In my opinion it is irresponsible not to consider sustainability and planetary health (a key, if not the major, determinant of the health of future generations) when developing nutrient and food-based dietary guidelines.

It should be noted that the group does not represent any national or international organisation or government. Guidelines are generally issued by authoritative bodies rather than self selected groups. While the bona fides and expertise of the leadership team and panel are not questioned, I would dispute the criticisms which appear to be levelled at all other groups which have suggested guidelines in the past.

Clare Collins is a Laureate Professor in Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Newcastle and Co-Director of the Food and Nutrition Research Program at the Hunter Medical Research Institute

When you look past the headline, all the papers indicate that higher intakes of processed and red meat are associated with a higher risk for all-cause mortality, heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. You have to question the recommendations made given that the data presented in the papers does not support it!

Of concern is that some major studies have been omitted including the Predimed study and the Diabetes Prevention Program. The authors question the validity of observational studies, but ignore the fact that this is the study design used to assess long term harm, just like we used to discover the link between smoking and lung cancer.

It would be impossible and unethical to put people on a test diet for 10 or 20 years to see what diseases they got and what they died from. The authors have not presented evidence that national dietary guidelines need updating. Poor eating habits are the leading cause of death worldwide. This report will confuse the public.

In Australia current data shows that the burden of disease would drop by 62% for heart disease, 41% for type 2 diabetes, 34% for stroke, and 22% for bowel cancer if all Australian ate like the Dietary Guidelines recommend. People need more support to adopt the healthiest eating patterns they can.

Dr Rosemary Stanton OAM, Nutritionist, Senior Visiting Fellow, School of Medical Sciences, University of New South Wales

The reviews look at the strength of evidence to support dietary guidelines from the US, the UK and WHO that suggest limiting red meat consumption to reduce risk of cardiovascular diseases and/or some cancers.

The strength of evidence was rated as ‘poor’ because:

- Trials in which people eat less red meat are not ‘blinded’, and are therefore regarded as ‘biased’.

- The difference in intake between those who reduced meat and those who did not was small. The largest trial that dominated the results showed a reduction of just 1.4 red and/or processed meat servings/week.

- Long-term adherence to specific dietary changes is poor.

- Most trials were ‘observational’ and so rated more poorly than randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In ‘observational’ trials, a cohort of people report their food consumption and their health is then followed over a period of years. Self-reported data is also subject to error and some trials only collect data on what subjects consume initially and at varying intervals thereafter.

- Long-term RCTs are challenging and not possible for many aspects of nutrition, especially when looking at the effects of a single food item. Also short-term RCTs (as all were in this review) cannot give results for mortality or many types of cancer may take years to develop and have no early signs.

Method of review

The authors used a systematic review methodology with GRADE results. Note that the 2013 revision of the Australian Dietary Guidelines also used a GRADE system.

In looking at why people do not want to reduce meat consumption, the current review found that meat eaters enjoyed meat, and had limited culinary skills to prepare meatless meals.

Relevance to Australian guidelines

For red meat, the GRADE system in Australia yielded the following results for red meat: “Consumption of greater than 100-120g/day of red meat is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (GRADE B)”. GRADE B indicates that the body of evidence from a minimum of 5 high quality studies can be trusted to guide practice.)

For processed meat, Australia’s Guidelines place them into ‘discretionary choices’ since no studies report health benefits from their consumption. Processed meats are also high in sodium, a nutrient for which the GRADED evidence is “convincing” (GRADE A) that reducing sodium intake decreases blood pressure.

Limitations:

The review did not compare meat eaters with those following a vegetarian diet but was designed to look at whether a reduction in red meat consumption is justified.

In spite of rating the evidence for limiting red and processed meat in selected dietary guidelines as ‘poor’, 12 of 14 authors own consumption of red and processed meat fit the guidelines with weekly consumption as follows: no meat (1 person), 0.5 serving (2 people), 1-2 servings (2 people), 2-3 servings (3 people), 3-4 servings (4 people), 3-5 servings (1 person), 6-7 servings (1 person).

Eleven out of 14 authors voted to continue current consumption levels for red and processed meat (which they note for North America and Europe is 3-4 times per week). Three out of the 14 voted to reduce consumption.

The authors did not consider ethical or environmental reasons for abstaining from meat in their recommendations but note these are valid and important concerns.

NOTE: One author of an accompanying editorial reports a conflict of interest with a popular book he has written (The Bad Food Bible: How and Why to Eat Sinfully).

In checking other authors, I note that several were also authors of a review examining the scientific basis for the World Health Organisation’s recommendations on sugar intake. Some of these authors, including the corresponding author of the current review on red and processed meat, declared they had received grants from the International Life Sciences Institute, a lobby group that protects the interests of powerful food companies.

Professor Mark L Wahlqvist AO is Emeritus Professor and Head of Medicine at Monash University and Monash Medical Centre. He is also Past President of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences

Several papers published as a collection in the Annals of Internal Medicine, deal with meat intake and the related cardiovascular, neoplastic and all-cause mortality health outcomes. They draw together different investigative methodologies and conclude that there is little evidence to reduce red meat consumption, whether fresh or processed, but without reference to food cultural relevance.

This flies in the face of most reports and dietary guidelines in recent times. Why?

The authors themselves devote much space to the limitations of observational studies on which conclusions are currently most dependent, especially bothered by ‘confounders. Yet it is the contextuality of population-based studies which is a strength. One paper reviews systematically what we know through randomised trials, notably the large Iowa Women’s Study, tenuous in its findings about meat. The general guidance which is proffered is that current food intake methodology and study design is unsatisfactory, precluding dietary guidelines, and that little if anything should be done to alter meat consumption. What the publications mean for evidence-based nutritional policy is usefully, if only partially, editorialised by Carroll and Doherty (1).

It must be said that the case for more restrained meat eating is generally made in socio-economically advantaged countries, where it is more afforded and sought for complex social reasons, not just health. There is growing subscription world-wide to limited meat consumption for environmental, ethical, budgetary and other considerations.

Nutritionally, the argument extends to what ‘energy intake room’ is left after meat is consumed to diversify the diet with other animal-derived, plant-derived and microbiomically-derived alternatives. From extensive and coherent evidence about optimal, sustainable and broadly affordable diets for humans, their biodiversity is key. That biodiversity signifies that we ought to discover how little meat we need, and not how much we can get. Ask the wrong question, get the wrong answer. The presumption that clinical feeding studies can be sufficiently contextual, and of sufficient sample size and duration for diverse populations to address an inappropriately focussed question on meat rather than dietary pattern is untenable. The nearest we could get to a proper question and answer, acceptable methodology, in reasonable time, and at manageable cost, would be a natural population-based experiment, whose findings were coherent with other lines of evidence in a portfolio rather than hierarchical fashion.

In the meantime, the present suite of papers is provocative and largely unhelpful.

Dr Lennert Veerman is Professor of Public Health at Griffith University. He has published on a broad range of topics including obesity and other risk factors for chronic disease.

The findings of these studies are broadly in line with previous findings. Per three serves of red or processed meat per week, the risk of death is 10 per cent higher. But there is uncertainty: the risk of death could be 15 per cent higher, or it could be that reducing meat consumption does not make you live longer.

It is mostly the interpretation that differs. The authors of these new studies judge the evidence to be weak, and the risks ‘very small’. They conclude that from a health point of view, there seems to be no reason to change meat consumption.

An alternative interpretation is that this is the best available evidence. And a 0-15 per cent lower risk of death for a modest reduction in meat consumption is a safe bet with attractive odds. Across the average life course in Australia, a 10 per cent lower risk of dying translates to living a year longer. That is not a ‘very small’ effect. It is a very large effect.

And there are other good reasons to moderate meat intake. For a growing number of people, concern about animal welfare is one. Consuming meat requires the killing of animals, many of which had miserable lives in the meat ‘industry’.

And then there is the environment. The production of meat is very inefficient compared to plant-based food. Researchers have concluded that ‘the meat on your plate is killing the planet’

Meat production contributes to land and water degradation, biodiversity loss, acid rain, coral reef degeneration and deforestation. And it causes almost a fifth of all greenhouse gas emissions, at a time when climate change ravages ecosystems and livelihoods around the planet.

So if you don’t accept your own health as enough reason to reduce your meat consumption, you might want to do so for the animals, and for the future of life on Earth.

Dr Joanna McMillan is an Accredited Practising Dietitian, Registered Nutritionist and Founder of Dr Joanna and Get Lean

For those that enjoy their meat this is undoubtedly a welcome suite of research! However, importantly what it is looking at is the impact on health of meat consumption and it is not assessing animal welfare or environmental considerations. Those factors are a whole other story. But if we put them aside and solely look at the health impact, these studies are extensive and the most comprehensive we have to date.

The bottom line is that the evidence of health benefits in terms of reducing our risk of heart disease, diabetes or cancer from reducing meat consumption from 3-4 times a week is low to very low. This is in line with the Lancet report published earlier in the year where other dietary factors were found to be far more significant in terms of impact on our health and mortality.

What we know from nutrition research is that ultimately dietary patterns are key over the impact of individual foods. Someone who consumes meat along with lots of vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds and fruits is entirely different from another who consumes lots of bacon, burgers and sausages with few plant foods and a high intake of refined grain foods such as burger buns and fried chips.

The best advice is to ensure you consume a plant-rich diet and you can choose, based on ethical and other beliefs, likes and dislikes, as to whether you also include meat.

Finally, humans have consumed meat since paleolithic times in many parts of the world – but not all – and it is an important source of nutrients for us, especially iron. Australian meat is from mostly pasture fed animals and much of the land is more suitable to such farming rather than planting crops. Our meat is very different to feedlot-produced intensive farming that dominates the US market. This must also be considered.

Professor Rachel Ankeny is Deputy Dean (Research) in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Adelaide, where she leads the Food Values Research Group. She is an expert on food ethics, and the relationship of science to food habits

Food is never just about nutrition or fuel: our food habits are aligned with our values and understandings, and we make our choices for a variety of reasons. Thus a key issue about any attempts to encourage changes in people's eating habits relates to the sociocultural meanings attached to meat. As our research has shown, in Australia many people associate meat with care or comfort, affluence, and even necessity as part of a good diet. Hence these recent and perhaps surprising findings are likely to be welcomed by many Australians who might find it difficult to change their consumption behaviours, particularly in relation to meat, even in the face of evidence about undesirable health effects.

Dr Andrea Braakhuis, Academic/Registered Dietitian, The University of Auckland

The group of systematic reviews to be published shortly are interesting, but not in contrast to the recommendations by leading nutrition guidelines. The guidelines generally suggest we consume small to moderate quantities of red meat as part of a balanced diet. The evidence that highly processed meat should be limited is a little more convincing than red meat as a whole.

The nutrition guideline recommending the least amount of red meat is the EAT Lancet planetary diet, which recommends around 7g a day of red meat (or 35g a day when combined with alternative meat sources). The EAT Lancet recommendation is based on climate change, not health, and is modelled off high input farming. Even so, red meat is still suggested a part of a healthy diet.

The authors of the systematic reviews conclude there is no significant benefit to reducing red meat consumption, however the strength of that conclusion is weak. It would be fair to say more research is warranted.

Professor Rod Jackson, Professor of Epidemiology, University of Auckland

I’ve reviewed much of the evidence covered in these papers over the years and have come to the conclusion that it is impossible to undertake a useful medium- to long-term (more than about 6 months) randomised controlled trial or cohort study to assess the effects of common foods like meat, vegetables or dairy products, or common nutrients like fats, proteins, or carbohydrates, on ‘hard’ outcomes like coronary disease, cancer or death.

The implications of this conclusion are three-fold:

1. We have spent hundreds of millions of dollar on studies incapable of giving us useful information because of inherent biases in medium- to long-term nutrition studies that are almost impossible to deal with. This is not a criticism of the researchers' ability to design studies, although they should have realised by now that the studies can’t be done well.

2. The misinformation given to the public, based on the result of these two types of seriously flawed study designs (for examining the medium- to long-term effects of common foods and nutrients), have led to huge confusion and likely harm. This includes the conclusions of these latest articles.

3. We need to re-educate many of the researchers who write these papers and the ‘experts’ who write so-called evidence based guidelines that they have to radically rethink what is considered acceptable evidence. These study designs are usually considered the gold standard study designs and many researchers and most guideline writers have yet to appreciate that they are next to useless.

The key bias in randomised controlled trials is cross-over between intervention and control groups. Not surprisingly, it has proven impossible to keep different groups on the diets they are randomised to for more than a month or two. The reason this is not surprising is that in randomised trials of a once a day drug versus an identical placebo for a couple of years we are very lucky if we get a 60-70% adherence rate. So how anyone can assume one could achieve anything like even a 50% adherence rate is beyond me.

Also, you can’t measure adherence because most people cannot accurately remember what they have been eating and tend to report what the researchers want to hear so we overestimate adherence.

As a result most randomised trials of diet on hard outcomes show minimal or no effects on outcomes, because the comparison groups gradually converge to have quite similar diets. That’s why the current studies report small or negligible effects.

The cohort studies are even worse. Firstly, questionnaires used to divide people into different baseline groups based on their diets are notoriously inaccurate so the studies start off with a major bias - the groups’ diets are probably not as different as the researchers think they are. Secondly the different baseline groups always differ in other ways over and above their diets and these other factors commonly cloud or exaggerate any real effects of diet. This is called confounding. Thirdly, long term cohort studies also suffer from the same cross-over problem that randomised trials suffer from. As they are generally longer than randomised trials, cross-over can be even worse.

I hope this explains why I don’t think these new studies reported in this journal are meaningful.

What we need to do instead is to bring together ALL the other evidence, including: from short-term randomised studies that are short enough to limit cross-over but can also only measure proxy outcomes like blood lipid levels or blood pressure levels; from ecological studies of whole populations; from biochemistry; from pathology and from long-term drug trials (e.g. with statins) etc. This is messy and requires people with serious expertise and experience, but evidence is messy. It doesn’t matter how many meta-analyses of randomised trials and cohort studies are done and how many millions of people are included. They are still seriously flawed.

Professor Nick Wilson, Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington

These new review findings lack a critical wider context in that there is an urgent need for a global shift to a more plant-based diets for planetary health reasons. The current patterns of meat consumption are completely unsustainable and are damaging the climate, polluting waterways, and depleting water supplies. Intensive livestock farming is also breeding microbes that are resistant to antibiotics and pandemic influenza can even arise from such dense collections of pigs and poultry. Such critical issues around sustainability are why the major EAT-Lancet Report recommends a shift to more plant-based diets – so we can feed a future population of 10 billion people within planetary boundaries.

From the direct human health risk perspective these new review findings are also out of sync with other major reviews – so they should also be seen in that context - for example, the very major review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (involving over 800 studies) on processed meat and red meat and increased risk of cancer. Furthermore, other lines of evidence indicate hazards of processed meat – it is invariably high in salt, which is a proven risk factor for raised blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Many forms of meat are also high in saturated fat – which is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Overall the evidence for predominantly plant-based diets being healthy is overwhelming. In particular, the Mediterranean diet (which is low in meat) has been consistently found to be associated with a lower risk of chronic diseases. But we need both healthy diets and a liveable planet – which is why shifting to sustainable food systems (from 'paddock to plate' or from 'seed to sewage') should be the dominant consideration around the world.

Australia; New Zealand; International; NSW; QLD; SA

Australia; New Zealand; International; NSW; QLD; SA