Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Behzad Fatahi is Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Technology Sydney

A magnitude 8.1 earthquake at a rather shallow depth of 69.7 km in the Gulf of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico occurred at 04:49 (UTC) on 8 September 2017. Pijijiapan in Chiapas state is the closest town to the earthquake epicentre (87 km away). In the Gulf of Tehuantepec, four tectonic plates namely Cocos Plate, Caribbean Plate, Panama Plate and North American Plate collide making the region one of the most unstable and evolving areas. Currently, the Cocos plate is subducting underneath North American and Caribbean plates. It is estimated that this earthquake happened within North American Plate and the event may have been triggered by continuous movement of middle America Trench (more than 70mm/year movement) which is only 100km away from the earthquake epicentre.

It is expected that coastal towns in Oaxaca and Chiapas states particularly those with reclaimed lands from the ocean should be carefully checked for possible failure of buildings and bridges. Major cities such as Salina Cruz, Juchitan de Zaragoza and Tapachula, as well as towns and villages near La Angostura lake should be inspected as a matter of priority. City of Tuxtla Gutiérrez located 200km away from the epicenter should be one of the most influenced area considering the large population of about half million.

Major dames namely Belisario Domínguez embankment dam (146m high and built 40 years ago) and Belisario Domínguez embankment dam (137m high and built 50 years ago) in Chiapas should be inspected carefully for possible landslides within the reservoir regions, water leakage through abutments and body of the dam as well as instability of the foundation. It should be noted that plutonic rocks (magma solidified at great depth) are abundant and exposed along the pacific coastal line in southern Mexico particularly Chiapas state, and in regions particularly near rivers are overlain by sedimentary rocks.

Assessment on initial observations indicate that poorly built low-rise buildings mainly built of brick and mortar, or heavy slabs on thin concrete columns (e.g. car parks), have been severally damaged contributing to causalities and death toll. Considering the past experience, it is expected that in regions further away from the epicenter particularly near Gulf of Mexico (e.g. Coatzacoalcos City) and along Coatzacoalcos river, significant ground subsidence and damage to lifelines such as pipelines and roads should have happened.

It is foreseen that due to the main earthquake and follow up aftershocks major landslides should be observed in the region. Only 3 months ago in June 2017, an earthquake with magnitude 6.9 occurred in western Guatemala near the border with Chiapas in Mexico triggering several major roadside landslides, and let’s not forget about 1985 Mexico City earthquake with magnitude of 8.0 with death toll of more than 5,000 people while significant damage occurred further away from the epicenter, where deep soft soil deposits (ancient lake bed) increased the devastating effects of earthquake on buildings and infrastructure.

Professor James Goff, is Director of the Australia-Pacific Tsunami Research Centre and Natural Hazards Research Laboratory, University of New South Wales.

The earthquake that struck off the state of Chiapas, SW Mexico was around a Magnitude 8.4. It occurred around the Middle America Trench, where the Cocos plate is plunging beneath the North American plate. This has caused a tsunami with predicted heights ranging from over 3.0 m for the Mexican coast.

However, it has also produced an ocean-wide tsunami with predicted heights ranging from 0.3-1.0 m for countries as far away as New Zealand which are in the direct line of fire, with smaller ones extending to countries such as Australia, Chile, Japan, Hawaii and the Philippines.

There have been no large ocean-wide tsunamis generated from this region of the Pacific Ocean in a long time and as such while we have predictive models for the extent of the waves, there is still some uncertainty as to how serious they may be once they strike the coast of distant shores. Predicted waves are relatively larger for the SW Pacific, notably New Zealand, because of the way they move across the Pacific. While predicted heights are small, those of us in the SW Pacific should continue to pay attention to advice from the authorities.

Dr Gary Gibson is Senior Seismologist, Seismology Research Centre, ESS

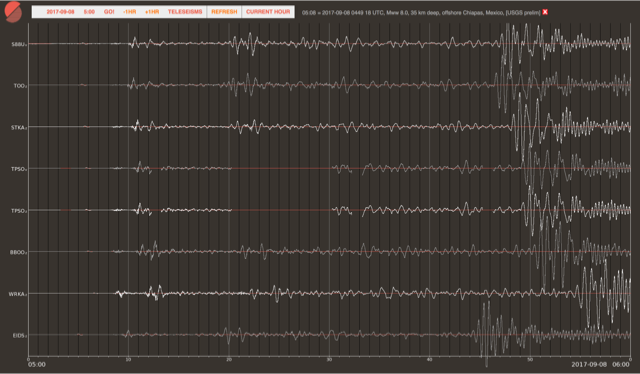

At 3:06 pm AEST this afternoon I was sitting at my desk doing the routine and relatively boring tasks that dominate the life of a seismologist, when an email from the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre announced a magnitude 8.0 earthquake along the south-east coast of Mexico.

I immediately opened the website showing data from the University of Melbourne seismograph network and there was no sign of an earthquake. Perhaps it was a false alarm, or an exercise in emergency response.

At 3:08 pm the first signs of ground motion from our Australian-based seismographs began.

At 3:10 pm the United States Geological Survey confirmed that a magnitude 8.0 earthquake had occurred along the coast of Mexico at 2:49 pm, and we were looking at the P waves (sound waves) that took about 20 minutes travelling through the body of the earth from Mexico to Australia.

The earthquake had been located and the magnitude determined before the seismic waves had reached Australia. We watched P waves following more complex travel paths arrive.

A magnitude 8.0 earthquake results from plate movement on a fault rupture that may be about 200 kilometres in length, with the Pacific Plate moving 5 to 10 metres or more downwards under Mexico and Guatemala.

Apart from the casualties and damage that an earthquake of this magnitude is likely to cause, such an earthquake can produce a tsunami that may result in significant additional casualties and damage, especially along the nearby coastline. The size of the tsunami depends on the deformation of the seafloor and is not easy to estimate without detailed knowledge of the earthquake motion.

Preliminary estimates suggested that the tsunami would reach the adjacent coast within tens of minutes, and that significant tsunami waves could arrive at greater distances along the nearby coast even hours after the earthquake. There is also a possibility of a smaller tsunami at much greater distances.

At 3:42 pm the first of the larger shear waves (S waves) arrived at the Geoscience Australia seismographs on the Queensland coast, and then at other seismographs across Australia over the following 15 minutes.

The earthquake surface waves that travel along the Earth’s surface are slower and will arrive over the next few hours.

Now the fist reports of fatalities and damage are coming in, the telephone has started to ring, and it is still not easy to estimate the consequences of the tsunami.

Australia; International; NSW; VIC

Australia; International; NSW; VIC