News release

From:

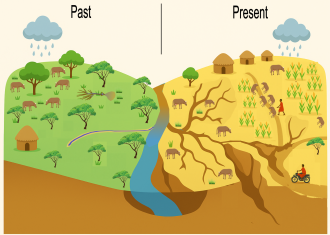

Recent fieldwork by Griffith University researchers has highlighted an African country is facing a rapidly escalating environmental crisis as severe gully erosion – locally termed “mega gullies” – advances across valuable agricultural landscapes.

Associate Professor Andrew Brooks and Research Fellow Dr Maarten Wynants from Griffith’s Precision Erosion and Sediment Management Research Group (PrESM) found the affected areas in Tanzania supported high-value farmland critical to local food security and economic stability.

“Without swift and coordinated action, the situation is a ‘time bomb’ that could inflict irreversible social, economic, and ecological damage,” Dr Wynants said.

“The onset of these mega gullies dates back 30–50 years, but recent evidence suggests they are now expanding on an exponential growth curve, meaning that each year they erode more and faster.”

Drivers of the problem

Through their years of fieldwork and study, Associate Professor Brooks and Dr Wynants said the trigger for this major erosion was caused by increasing human pressures and changes to how they interact with their environment, including:

- Overgrazing

- Deforestation

- Removal of natural vegetation for farmland, driven a rapidly growing population in Tanzania (doubling about every 25 years and currently at 70 million people)

- Forced settling of nomadic pastoralists

- And loss of socio-economic capital (the loss of indigenous skills during the colonial period, a lack of governance of natural resources, and no investment in soil conservation).

“There are, of course, also some natural factors that make the region so vulnerable to this issue, such as volcanic and dispersive soils, variable rainfall with switching of droughts and extreme floods, and hilly terrain,” Associate Professor Brooks said.

But primarily, the major shift in human land use played the critical role.

“Following independence, many Maasai pastoralists relocated into permanent settlements, abandoning the nomadic grazing patterns that once allowed landscapes to recover during seasonal migrations,” Dr Wynants said.

“Today, land that was historically grazed only seasonally is permanently cropped and overgrazed, placing immense strain on fragile volcanic and dispersive soils.”

Social, economic, and ecological impacts

The research team said not only did the mega gullies threaten agricultural lands, grazing lands, roads, and bridges, they also posed risks to schools, homes and community areas.

In a region where about 70 per cent of people relied on subsistence farming, the loss of arable land directly jeopardised both income and food security.

“Infrastructure was equally at risk: two bridges in the study region, each costing about USD $100,000, were destroyed within a decade of installation – an immense setback in a nation striving to develop essential services,” Dr Wynants said.

“Collapsing roads and bridges also stop people from selling excess produce to distributors or taking it to the markets, so they cannot earn money.”

Downstream, sediment from eroded landscapes was rapidly filling reservoirs and lakes, degrading water quality and threatening biodiversity hotspots such as Lake Manyara National Park, a UNESCO Man and Biosphere reserve which is home to more than 350 bird species and a wide range of typical African terrestrial wildlife such as lions and elephants.

Solutions and paths forward

In response to these erosion impacts, Griffith researchers, in collaboration with the Tanzanian Nelson Mandela African Institution for Science and Technology, Ghent University, Belgium, and Tanzanian stakeholders and NGOs such as the Women's Agri-Enviro Vision, have initiated monitoring stations and demonstration projects using indigenous, low-cost erosion-control techniques – including slow-forming terraces, earth bunds, and leaky dams – but these measures can only stabilise smaller gullies.

The team emphasised large-scale restoration, significant financial investment, and major societal shifts in livestock management and soil stewardship were urgently needed to halt the further advancement of mega gullies to protect Tanzania’s future.

"To completely stop this problem, we need a total shift where people destock and better regulate livestock grazing, but also invest in soil improvement and management,” Associate Professor Brooks said.

“And there is also a need to set up a large investment fund supporting the ongoing restoration and future prevention of these mega gullies.”

Multimedia

Australia; QLD

Australia; QLD