News release

From:

280,000-year-old fossils rewrite rock wallaby history, epic journeys shaped survival

Rock wallabies are widely regarded as shy cliff-dwellers, rarely venturing far from the safety of their rocky shelters. But new fossil evidence suggests this reputation may only tell part of the story.

A study published in Quaternary Science Reviews found that while most rock wallabies living in central Queensland around 280,000 years ago occupied small home ranges, a few individuals were unexpectedly mobile. At least one travelled more than 60 kilometres across the landscape, including crossing the crocodile-infested Fitzroy River.

Some studies of modern rock wallabies have suggested gene flow between colonies. But this is the first direct evidence of long-distance dispersal occurring in individual rock wallabies. While uncommon, these long-distance movements are significant. They can help maintain connections between otherwise isolated populations, supporting genetic diversity and facilitating long-term resilience. The findings have implications for contemporary conservation efforts.

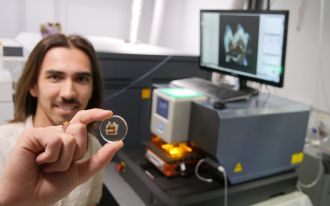

The research was led by University of Wollongong (UOW) PhD candidate Chris Laurikainen Gaete in collaboration with the Queensland Museum, CQUniversity, Purdue University, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and Capricorn Caves.

“Based on modern observation, we expected rock wallabies to be extremely local,” Mr Laurikainen Gaete said. “While this proved true for the majority, a small number travelled far beyond expected ranges. One travelled more than 60 kilometres – an extraordinary distance for a species considered sedentary.”

Professor Anthony Dosseto from the Wollongong Isotope Geochronology Laboratory said the team analysed fossil remains recovered from the Mount Etna Caves near Rockhampton.

“We used the chemical signatures preserved in fossil teeth to reconstruct how individual kangaroos – from the little pademelon to the giant Protemnodon – moved through the landscape,” he said. “Most were homebodies, relying on local resources – with a few notable and important exceptions.”

Dr Scott Hocknull, Principal Research Fellow in Applied Palaeontology at CQUniversity, said the study demonstrated the power of new isotopic techniques to reconstruct ancient animal behaviour at the level of individual lives.

“By tracking individual wallabies we can detect rare but important behaviours that would otherwise remain invisible,” he said.

“Long-term species survival depends on individuals being able to move between habitats. These movements happen irregularly and over very long timescales, meaning they’re rarely captured by traditional field studies. Fossils allow us to see that hidden flexibility.”

Today, small populations of rock wallabies are still found in central Queensland, in the same areas they lived in the past. We don’t know whether movement between these groups still occurs today. But with major roads and development now dividing the landscape, humans might inadvertently be creating barriers for these rare but crucial dispersal events.

“Future management shouldn’t view rock wallabies as isolated colonies,” Mr Laurikainen Gaete said. “Long-distance dispersal has always been part of their natural history and by protecting landscape connectivity, we ensure this deep-time behaviour remains part of their future survival.”

About the research

‘Niche partitioning and limited mobility characterise Middle Pleistocene kangaroos from eastern Australia’ by Christopher Laurikainen Gaete, Scott Hocknull, Clement Bataille, Andrew Lorrey, Katarina Mikac, Rochelle Lawrence and Anthony Dosseto was published in Quaternary Science Reviews.

Multimedia

Australia; QLD

Australia; QLD