Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Adolfo Lugo-Rios is a Research Fellow in Marine Science/ Geospatial Science at Queensland University of Technology

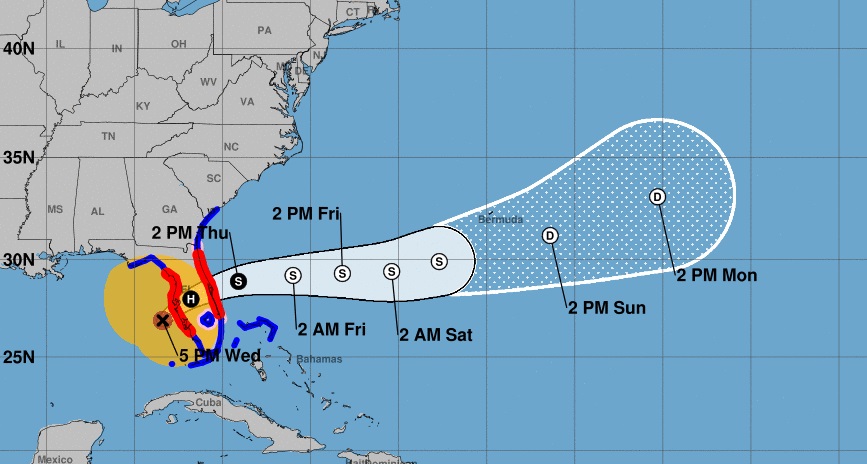

Hurricane Milton has struck the west-central coast on the Florida peninsula on 8pm EDT Wed 9 October and crossed Florida into the Atlantic 9 hours later passing over Tampa Bay and Orlando, FL. Milton impacted as a category 3 hurricane producing heavy rain along its path. It is not expected to return to land or to intensify again.

What makes Milton and this Atlantic hurricane season remarkable is that the season started early in June producing hurricane Beryl, reaching category 5, the earliest category 5 of the season, then the season went quiet until late September, when Helene (formed on 24 Sep, achieving category 4) and Milton (formed on 05 Oct, achieving category 5) formed within two weeks, not mentioning other 5 storms: Isaac, Kirk, Joyce, Leslie and tropical depression-10 also occurred in this period. It has to be mentioned that typically, in early September the hurricane season achieves its peak, but this year, the season peak has shifted to the end of September.

Notably both Helene and Milton experienced a process called rapid intensification in the Gulf of Mexico, which is that the hurricane intensity increases abruptly (an increase of 15m/s (55km/hr) in a day or less). It seems that that the rapid intensification of Milton is posed to set a new world record, surpassing the rapid intensification of Otis (2023) and Patricia (2015) both in the Eastern Pacific.

Although it is hard to determine if the rapid intensification of these tropical cyclones and the very active end of season can be attributed to climate change, it has been recognized that it is very likely that tropical cyclones all around the world will be more intense. At the same time, it is expected that a warmer climate will produce fewer tropical cyclones.

Note that the US National Hurricane Center uses the Saffir Simpson hurricane scale to measure the hurricane wind intensity it uses 5 category numbers, just like the scale used by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, however, both scales are not directly comparable as they follow different methodologies and threshold values. Neither account for the risk associated with rainfall.

Mr Andrew Gissing is the CEO at Natural Hazards Research Australia

Hurricane Milton is a major hurricane likely to bring destructive winds, flooding and coastal erosion as it crosses the coast of Florida, US. Hurricanes of this magnitude are extremely dangerous – there is a significant risk to life and inevitably the event will cause severe damage to property and infrastructure. Despite warnings for people to evacuate, research shows that often many do not, for a variety of reasons, leaving them exposed to impacts.

This will be the third landfalling hurricane to impact Florida in 2024, the other two landfalling hurricanes being Debby and Helene. Some locations in the path of Milton were significantly damaged only weeks ago by Hurricane Helene. These sequential disasters pose additional risks as impacts are likely to compound and cause greater damage. In a warmer world both here in Australia and overseas, the impacts of hurricanes and cyclones will be exacerbated by rising sea levels and greater intensities.

In Australia, hurricanes are called Tropical Cyclones. Tropical Cyclones have impacted communities north of Coffs Harbour on the east coast and to the southern tip of Western Australia. The Australian Tropical Cyclone season stretches from 1 November to 30 April. This year is 50 years since Darwin was all but destroyed by Cyclone Tracy. Cyclones have impacted areas that are now significantly populated, for example the Gold Coast where in 1954 a severe tropical cyclone crossed the coast. A repeat today would result in a major disaster. Recent events in the US should be a reminder to Australian communities to get ready for the upcoming cyclone season.

The impacts of cyclones can be reduced by avoiding development in areas at high risk of flooding, strengthening the resilience of buildings against strong winds, investing in flood mitigation and coastal defences including those provided by nature and giving early warnings to communities when cyclones threaten.

Associate Professor Paula Dootson is Research Lead with Natural Hazards Research Australia and Chief Investigator at the Centre for Future Enterprise at Queensland University of Technology

The biggest issue emergency services agencies face at the moment is managing the conflicting information and misinformation being spread on news media and social media that is preventing or delaying evacuation in at-risk communities. The 1000s of videos being shared showing people in the storm, in flood waters, and in the extreme wind conditions, is in direct conflict with emergency agencies instructing people to get out or to take shelter.

The community is also more likely to receive information about what to do to prepare for the hurricane from influencers or unofficial sources on social media than from official agencies.

There needs to be constant myth-busting/fact-checking of information being circulated by agencies' public information teams, direct lines of communication to the news media to combat misinformation, and agencies releasing their own videos to combat misinformation.

Useful videos agencies can release include using CGI to show how storm surges can rise above houses, and can also be used to show the dangers of what flood water can carry (e.g., debris, sewerage, powerlines, etc.). Visuals that agencies circulate need to be educative but they also need to show people what to do. The user-generated content circulating from community members filming the hurricane effects creates fear, without showing any of the protective actions people should have taken or be taking to save their lives and property.

Relevant conflicting cues research funded by BNHCRC:

- Dootson, Paula, Kuligowski, Erica, Greer, Dominique, Miller, Sophie A., & Tippett, Vivienne (2022) Consistent and conflicting information in floods and bushfires impact risk information seeking, risk perceptions, and protective action intentions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 70, Article number: 102774.

- Conflicting cues with emergency warnings impacts protective action https://www.bnhcrc.com.au/hazardnotes/59

- What agencies can do about it: Addressing conflicting cues during natural hazards: lessons from emergency agencies https://www.bnhcrc.com.au/hazardnotes/72

Relevant visuals research funded by BNHCRC:

- Dootson, Paula, Kuligowski, Erica, & Murray, Scott (2023) Using videos in floods and bushfires to educate, signal risk, and promote protective action in the community. Safety Science, 164, Article number: 106166.

Professor Paula Jarzabkowski is a Professor of Strategic Management at The University of Queensland

The damage and loss from Hurricane Milton will affect the already escalating prices of disaster insurance in Australia. Early predictions suggest at least a US$20 billion cost of insurance claims from Milton and this follows hard on the insured losses from Hurricane Helene which are reported to be at least US$6 billion.

Beyond being devastating for those directly affected, the losses from Hurricane Milton show how interconnected global systems are, as more extreme weather disasters in highly urbanised areas in one country increase economic and insurance costs around the world.

Disaster insurance is already unaffordable and unavailable for many. Hurricane Milton will exacerbate that problem.

Dr Rob Nicholls is a Senior Research Associate at the University of Sydney

Misinformation is one of the challenges facing the US Federal Emergency Management Agency Administration (FEMA) in preparing for what FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell called ‘catastrophic impacts’ from Hurricane Milton.

FEMA has become an election issue in the US. Presidential candidate Donald Trump and some Republican lawmakers have labelled FEMA as 'untrustworthy'. They allege that FEMA has misused funds. The claims by Trump include that FEMA is responsible for migrants receiving money allocated for disaster aid. President Joe Biden said Wednesday there has been a ‘reckless, irresponsible and relentless promotion of disinformation and outright lies.’

The issue here is that misinformation can threaten the lives of people who believe it. FEMA is assisting in the evacuations ordered by State Governors (including Trump rival, Ron DeSantis) and will run the recovery process. The reason that FEMA is targeted by Republicans is that it makes comments, such as those by Criswell that 'we continue to see the impacts of climate change cause more severe weather events across the US.' This is a clear example of where misinformation about climate change can lead to people putting themselves in danger.

Associate Professor Iftekhar Ahmed is from the School of Architecture and Built Environment at University of Newcastle

Tropical cyclones, or ‘hurricanes’ as they are called in America, are clearly linked to global warming due to climate change, as pointed out by scientists for a while now, for example in a 2012 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

A key message is climate change will make hurricanes more ferocious and frequent and can impact areas without a history of the hazard. Hurricane Milton bore down on Tampa Bay – an area that hadn’t seen a hurricane in over a century.

The increasing magnitude of recent hurricanes has meant their impact has stretched 500 kilometres inland, as with the very recent Hurricane Helene affecting North Carolina.

This presents a challenge for emergency management planning in areas where it is perceived that there is no risk. All coastal areas are now at risk because of the erratic and unpredictable nature of climate change impacts.

A nationwide, anticipatory, hurricane preparedness program with a wide inland catchment that can spring into quick action is necessary in all coastal nations.

Building codes for coastal areas, whether they have experienced a hurricane or not, need to be implemented, together with designated emergency evacuation centres.

We should not wait for a hurricane to happen before taking such measures.

Dr Nader Naderpajouh is Head of the School of Project Management and an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering at The University of Sydney

Hurricane Milton is a clear example that both the intensity and frequency of disasters are increasing as a result of climate change, with record high expected impacts, and less than two weeks after a major Hurricane in the area.

It highlights the need for changing the planning paradigm to address compound disasters including overlap in recovery phases, agility of responses, and complexity of resource needs in consecutive disasters. The order of complexity for these scenarios is significantly higher, for example, how temporary accommodation can address the overlapping needs, how evacuations are managed while there is a stream for population to return, and how should we plan the timeline of the recovery.

It is also important to discuss Hurricane Milton in view of the US election, and what is the prospect for policies and available resources for disaster planning and response. There are clear differences in recognition of climate change and its impact, as well as how the response and recovery should be supported.

The hurricane may impact the election in many aspects, from operation of the election to awareness about issues, reviving the memories of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, when Republican Governor of New Jersey endorsed the support of the Democratic President of the time two weeks before the election, indicating that climate change and its impact will be agnostic to political party lines.

Professor Nick Titov is a Professor of Psychology in the School of Psychological Sciences at Macquarie University, Executive Director of MQ Health and director of the University’s free digital mental health service, MindSpot

Natural disasters can impact all aspects of someone’s life, affecting family, community, health, living arrangements, finances and employment. It shakes our sense of control, and our expectations and belief in the safety and predictability of the world, undermining our confidence that we can protect our loved ones from harm.

Because disasters are often sudden and unexpected we may be unprepared, and this can also have an impact on our ability to respond effectively, both in the moment and during the recovery process.

Initially, people involved in disaster situations often report feeling energised. This is a survival response that enables us to take the actions necessary to manage threats and reduce risks.

Afterwards, people react in different ways: feeling numb, sad, anxious, tearful, on edge, angry, confused, tense, exhausted, drained or any combination of these. Some people also have physical symptoms such as headaches, trouble sleeping or low energy, or cognitive problems such as difficulty concentrating or thinking clearly. Some people may develop depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or resort to drugs or alcohol to try to cope.

However we react, it is important to know that not coping is not a sign of weakness and we can seek help and support to rebuild our resilience.

Dr Steve Turton is an Adjunct Professor in Environmental Science (climate science) at CQUniversity

At one stage (near the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico), Major Hurricane Milton had sustained 1-min maximum winds near 300 km/h. This is considered near the theoretical maximum velocity for tropical cyclones for our planet. As we continue to trap extra heat in our climate system, due to rising greenhouse gases from human activities, will we need to re-consider the 1-5 scale used for tropical cyclones (hurricanes and typhoons) and introduce a new Category 6 scale?

Dr Liz Ritchie-Tyo is Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the Monash School of Earth, Atmosphere & Environment and Department of Civil Engineering

As Hurricane Milton makes landfall over the central Florida coast, this system highlights the importance of understanding all the potential impacts of any landfalling tropical cyclone and how these differ depending on your location. Hurricane Milton is an example of the combination of impacts that can occur in a major tropical cyclone – damaging winds and high coastal storm surge over a large region, and heavy rainfall. Depending on local conditions, the storm surge can cause high inundation well inland of the coast, and heavy rainfall can cause freshwater flooding in areas that don’t normally flood, and landslides and mudslides in regions of steep terrain.

It is important that we understand the potential for these landfalling impacts across communities not just in the US, but globally. To address this question, Monash has been investigating how tropical cyclone behaviour has changed historically, and is projected to change under future climate scenarios in South East Asia, Australia and the South Pacific, to assess the risk and likelihood that any particular piece of coastline could be affected.

Regardless of how our changing climate may affect the nature of tropical cyclones, Hurricane Milton is a reminder that major tropical cyclones with devastating impacts can make landfall anywhere along our tropical cyclone-prone coastlines. Being prepared for an event that might never happen costs far less than regretting a lack of preparedness afterwards.

Australia; International; QLD

Australia; International; QLD