News release

From:

A new study in Nature by an international team of researchers opens a window into hunter-gatherer lifestyles 40,000 years ago.

Archaeological excavations at the site of Xiamabei in the Nihewan Basin of northern China have shed light on the presence of innovative behaviours and unique sets of toolkits.

Director of Griffith’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution was part of the team that included researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the University of Bordeaux, as well as scientific partners in Spain.

Professor Petraglia and his colleagues reported the discovery of ochre-processing materials and an assemblage of tools dated to around 40,000 years ago at Xiamabei.

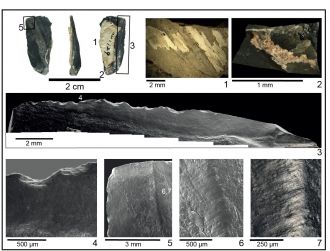

Ochre pieces found in the area revealed that different types of ochre were processed using abrasion and pounding to produce powders of different colours and grain sizes.

The assemblage of stone tools, comprising 382 artefacts, demonstrated novel and complex technological capacities, such as miniaturisation (almost all of the pieces are smaller than 40mm, and most are smaller than 20mm) and hafting (a process by which an artefact is attached to a handle or strap).

The discovery of a new culture suggests processes of innovation and cultural diversification occurring in Eastern Asia during a period of genetic and cultural hybridisation.

Although previous studies have established that Homo sapiens arrived in northern Asia by about 40,000 years ago, much about the lives and cultural adaptations of these early peoples, and their possible interactions with archaic groups, remains unknown.

Professor Petraglia said the assemblage of cultural traits at Xiamabei was unique and did not correspond with those found at other archaeological sites inhabited by archaic populations, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, or to those generally associated with the expansion of H. sapiens.

“This may reflect an initial colonisation by modern humans, potentially involving cultural and genetic mixing with local Denisovans, who were perhaps replaced by a later second arrival,” Professor Petraglia said.

“Our findings show that current evolutionary scenarios are too simple, and that modern humans, and our culture, emerged through repeated but differing episodes of genetic and social exchanges over large geographic areas, rather than as a single, rapid dispersal wave across Asia.”

The research ‘Innovative ochre processing and tool use in China 40,000 years ago’ has been published in Nature.

Multimedia

Australia; International; QLD

Australia; International; QLD