News release

From:

Peer reviewed Observational Study N/A

Dinosaur “mummies” might not be as unusual as we think

Data from fossils and modern carcasses indicates simple path to preserving dinosaur skin

A process of desiccation and deflation explains why dinosaur “mummies” aren’t as exceptional as we might expect, according to a study published October 12, 2022 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Stephanie Drumheller of the University of Tennessee–Knoxville and colleagues.

The term “mummy” is often used to describe dinosaur fossils with fossilized skin, which are relatively rare. It is commonly suggested that such fossils only form under exceptional circumstances and that a carcass must be shielded from scavenging and decomposition by rapid burial and/or desiccation in order for skin to become fossilized. In this study, Drumheller and colleagues combine fossil evidence with observations on modern animal carcasses to propose a new explanation for how such “mummies” might form.

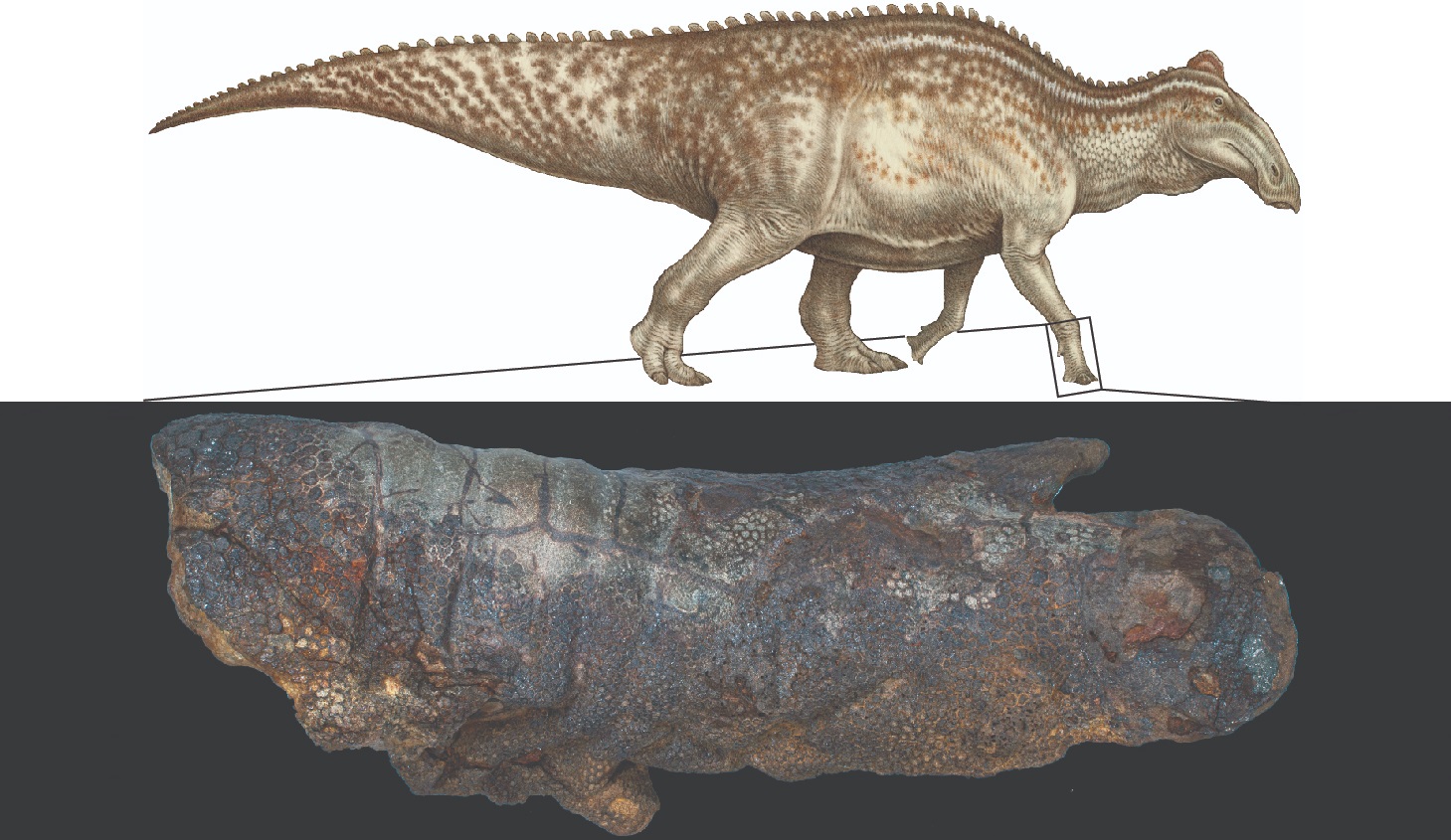

The researchers examined a fossil of a dinosaur called Edmontosaurus from North Dakota which preserves large patches of desiccated and seemingly deflated skin on the limbs and tail. They identified bite marks from carnivores upon the dinosaur’s skin. These are the first examples of unhealed carnivore damage on fossil dinosaur skin, and furthermore, this is evidence that the dinosaur carcass was not protected from scavengers, yet it became a mummy nonetheless.

Modern animal carcasses are known to be often emptied out as scavengers and decomposers target internal tissues, leaving behind skin and bone. The authors propose that damage to this dinosaur’s skin from this incomplete scavenging would have exposed its insides and allowed a similar process to occur, after which the skin and bones became slowly desiccated and buried.

This process, which the authors call “desiccation and deflation,” is common with modern carcasses and explains how dinosaur mummies might form under relatively ordinary circumstances. The authors stress that there are likely numerous pathways by which a dinosaur mummy might develop. Understanding these mechanisms will guide how paleontologists collect and interpret such rare and informative fossils.

Clint Boyd, Senior Paleontologist at the North Dakota Geological Survey, adds: “Not only has Dakota taught us that durable soft tissues like skin can be preserved on partially scavenged carcasses, but these soft tissues can also provide a unique source of information about the other animals that interacted with a carcass after death.”

Multimedia

International

International