News release

From:

Peer-reviewed Observational study Animals

Body lice may be bigger plague spreaders than previously thought

Study could challenge widespread view that fleas, rats are the only contributors to outbreaks

A new laboratory study suggests that human body lice are more efficient at transmitting Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague, than previously thought, supporting the possibility that they may have contributed to past pandemics. David Bland and colleagues at the United States’ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Biology on May 21st.

Y. pestis has been the culprit behind numerous pandemics, including the Black Death of the Middle Ages that killed millions of people in Europe. It naturally cycles between rodents and fleas, and fleas sometimes infect humans through bites; thus, fleas and rats are thought to be the primary drivers of plague pandemics. Body lice—which feed on human blood—can also carry Y. pestis, but are widely considered to be too inefficient at spreading it to contribute substantially to outbreaks. However, the few studies that have addressed lice transmission efficiency have disagreed considerably.

To help clarify the potential role of body lice in plague transmission, Bland and colleagues conducted a series of laboratory experiments in which body lice fed on blood samples containing Y. pestis. These experiments involved the use of membrane feeders, which simulate warm human skin, enabling scientists to study transmission potential in a laboratory setting.

They found that the body lice became infected with Y. pestis and were capable of routinely transmitting it after feeding on blood containing levels of the pathogen similar to those found in actual human plague cases.

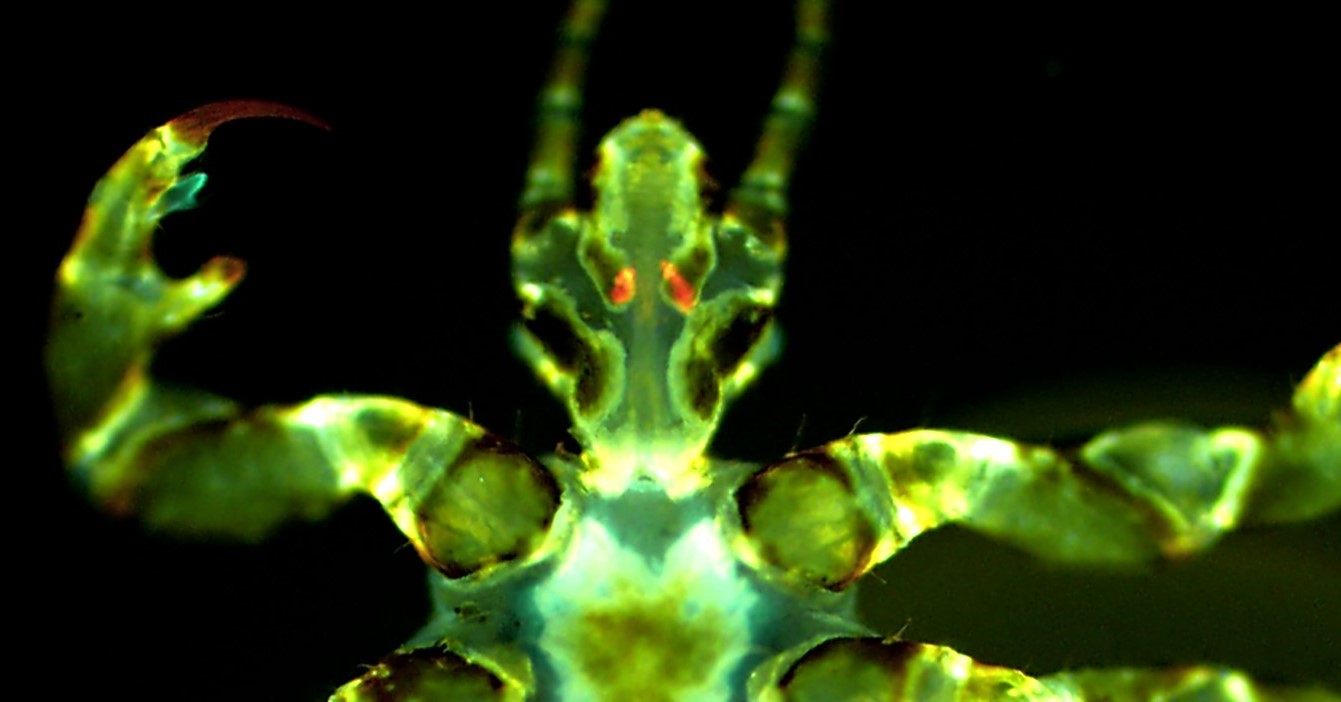

They also found that Y. pestis can infect a pair of salivary glands found in body lice known as the Pawlowsky glands, and lice with infected Pawlowsky glands transmitted the pathogen more consistently than lice whose infection was limited to their digestive tract. It is thought that Pawlowsky glands secrete lubricant onto the lice’s mouthparts, leading the researchers to hypothesize that, in infected lice, such secretions may contaminate mouthparts with Y. pestis, which may then spread to humans when bitten.

These findings suggest that body lice may be more efficient spreaders of Y. pestis than previously thought, and they could have played a role in past plague outbreaks.

The authors add, “We have found that human body lice are better at transmitting Yersinia pestis than once appreciated and achieve this in more than one way. We describe a new bite-based mechanism in which a set of accessory salivary glands unique to lice, termed the Pawlowsky glands, become infected with Y. pestis and secrete lubricant containing plague bacilli onto the insect’s mouthparts prior to blood feeding.”

#####

International

International