News release

From:

Reanalysis of the prehistoric cemetery Jebel Sahaba, Sudan, one of the earliest sites showing human warfare (13,400 years ago), suggests that hunter-fisher-gatherers engaged in repeated, smaller conflicts. The findings are published in Scientific Reports. Healed trauma on the skeletons found in the cemetery indicates that individuals fought and survived several violent assaults, rather than fighting in one fatal event as previously thought.

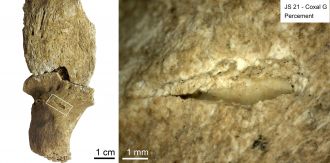

Isabelle Crevecoeur, Daniel Antoine and colleagues reanalysed the skeletal remains of 61 individuals, who were originally excavated in the 1960s, using newly available microscopy techniques. The authors identified 106 previously undocumented lesions and traumas, and were able to distinguish between projectile injuries (from arrows or spears), trauma (from close combat), and traces associated with natural decay. They found 41 individuals (67%) buried in Jebel Sahaba had at least one type of healed or unhealed injury. In the 41 individuals with injuries, 92% had evidence of these being caused by projectiles and close combat trauma, suggesting interpersonal acts of violence.

The authors suggest that the number of healed wounds matches sporadic and recurrent acts of violence, which were not always lethal, between Nile valley groups at the end of the Late Pleistocene (126,000 to 11,700 years ago). They speculate these may have been repeated skirmishes or raids between different groups. At least half of the injuries were identified as puncture wounds, caused by projectiles like spears and arrows, which supports the authors’ theory that these injuries happened when groups attacked from a distance, rather than during domestic conflicts.

Multimedia

International

International