News release

From:

Converging ocean currents bring floating life and garbage together

Community science survey reveals abundance of sea creatures in the North Pacific “Garbage Patch”

The North Pacific “Garbage Patch” is home to an abundance of floating sea creatures, as well as the plastic waste it has become famous for, according to a study by Rebecca Helm from Georgetown University, US, and colleagues, publishing May 4th in the open access journal PLOS Biology.

There are five main oceanic gyres — vortexes of water where multiple ocean currents meet — of which the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) is the largest. It is also known as the North Pacific “Garbage Patch” because converging ocean currents have concentrated large amounts of plastic waste there. However, many floating ocean creatures, such as jellyfish (cnidarians), snails, barnacles and crustaceans, may also use currents to travel through the open ocean, but little is known about where they live.

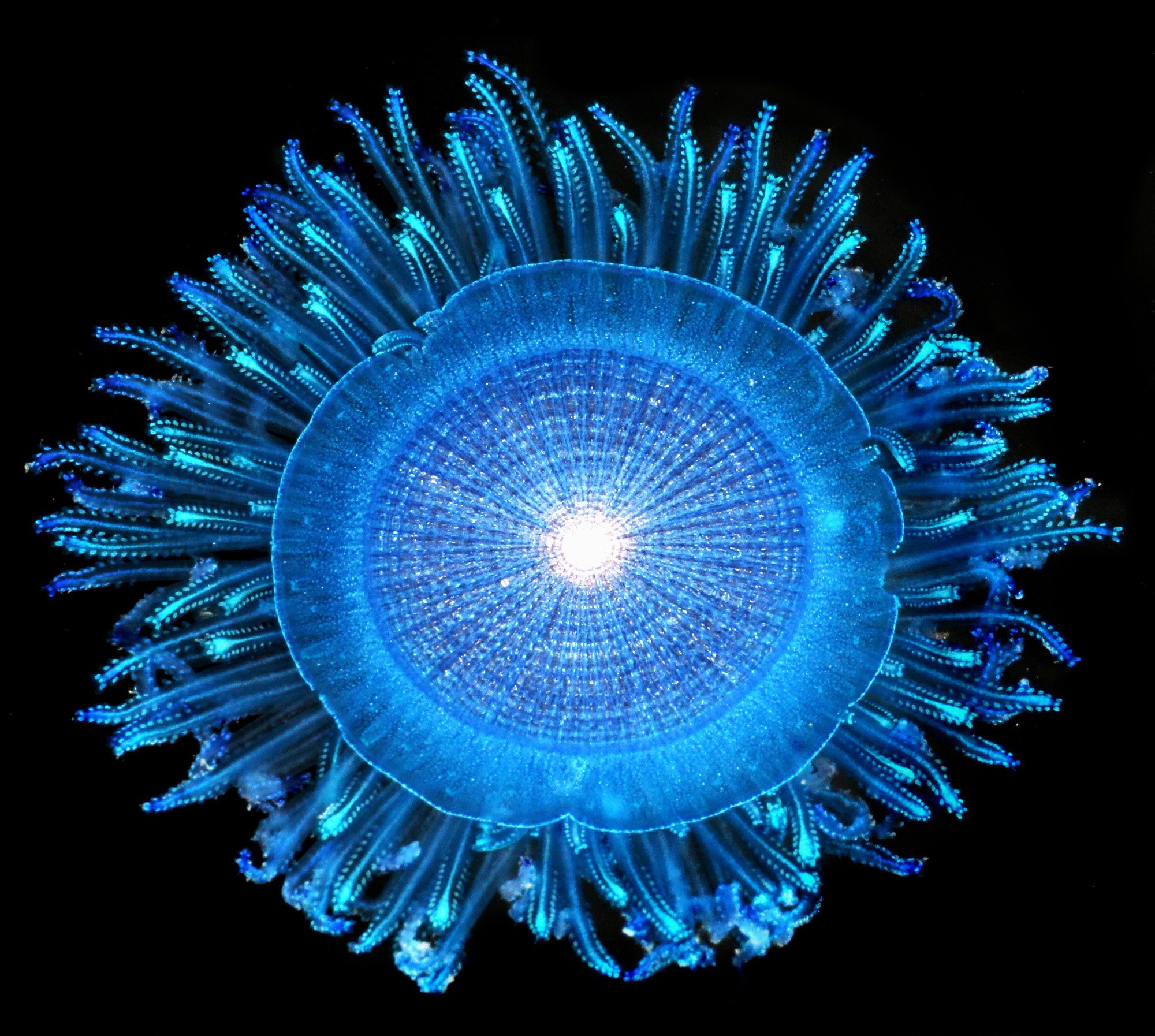

The researchers took advantage of an 80-day long-distance swim through the NPSG in 2019 to investigate these floating lifeforms, by asking the sailing crew accompanying the expedition to collect samples of surface sea creatures and plastic waste. The expedition’s route was planned using computer simulations of ocean surface currents to predict areas with high concentrations of marine debris. The team collected daily samples of floating life and waste in the eastern NPSG, and found that sea creatures were more abundant inside the NPSG than on the periphery. The occurrence of plastic waste was positively correlated with the abundance of three groups of floating sea creatures: sea rafts (Velella sp), blue sea buttons (Porpita sp) and violet sea snails (Janthina sp).

The same ocean currents that concentrate plastic waste at oceanic gyres may be vital to the life cycles of floating marine organisms, by bringing them together to feed and mate, the authors say. However, human activities could negatively impact these high-sea meeting grounds and the wildlife that depends on them.

Helm adds, “The ‘garbage patch’ is more than just a garbage patch. It is an ecosystem, not because of the plastic, but in spite of it.”

Multimedia

International

International