News release

From:

Comment from NZ author, Professor Vic Arcus

Professor Arcus is part of an international research team that used a New Zealand-led theory developed at the University of Waikato to analyse a designer enzyme. He explains how this theory was developed and used.

"The theory developed in New Zealand is called “Macromolecular Rate Theory (MMRT)”. It was developed to describe the temperature dependence of enzyme rates and has been used subsequently to describe biological rates at increasing scales - from enzymes to ecosystems. For example, we used MMRT to describe the temperature dependence of global photosynthesis. MMRT makes some predictions about how enzymes will behave and these predictions were tested, using atomistic computer simulations of the designer enzymes. The 1000-fold increase in activity for the best designer enzyme is the result of increasing cooperativity across the whole molecule."

Media Release from University of Bristol: Understanding enzyme evolution paves the way for green chemistry

Researchers at the University of Bristol have shown how laboratory evolution can give rise to highly efficient enzymes for new-to-nature reactions, opening the door for novel and more environmentally friendly ways to make drugs and other chemicals.

Scientists have previously designed protein catalysts from scratch using computers, but these are much less capable than natural enzymes. To improve their performance, a technique called laboratory evolution can be used, which American chemical engineer Frances Arnold pioneered and for which she received the Nobel Prize in 2018. Directed evolution imitates natural selection, allowing scientists to use the power of biology to improve the ability of proteins to carry out tasks such as catalysing a specific chemical reaction.

But although the research team had recently used laboratory evolution to improve a designed enzyme by more than 1,000 fold, it was unknown how evolution boosts its activity. Until now.

Lead author Professor Adrian Mulholland of Bristol’s School of Chemistry said: “Evolution can make catalysts much more active. The thing is, evolution works in mysterious ways: for example, mutations that apparently improve catalysis often involve changes in amino acids far from the active site where the reaction happens.”

“We wanted to understand how evolution can transform inefficient designer biocatalysts into highly active enzymes.”, the first author of the study Dr Adrian Bunzel, added.

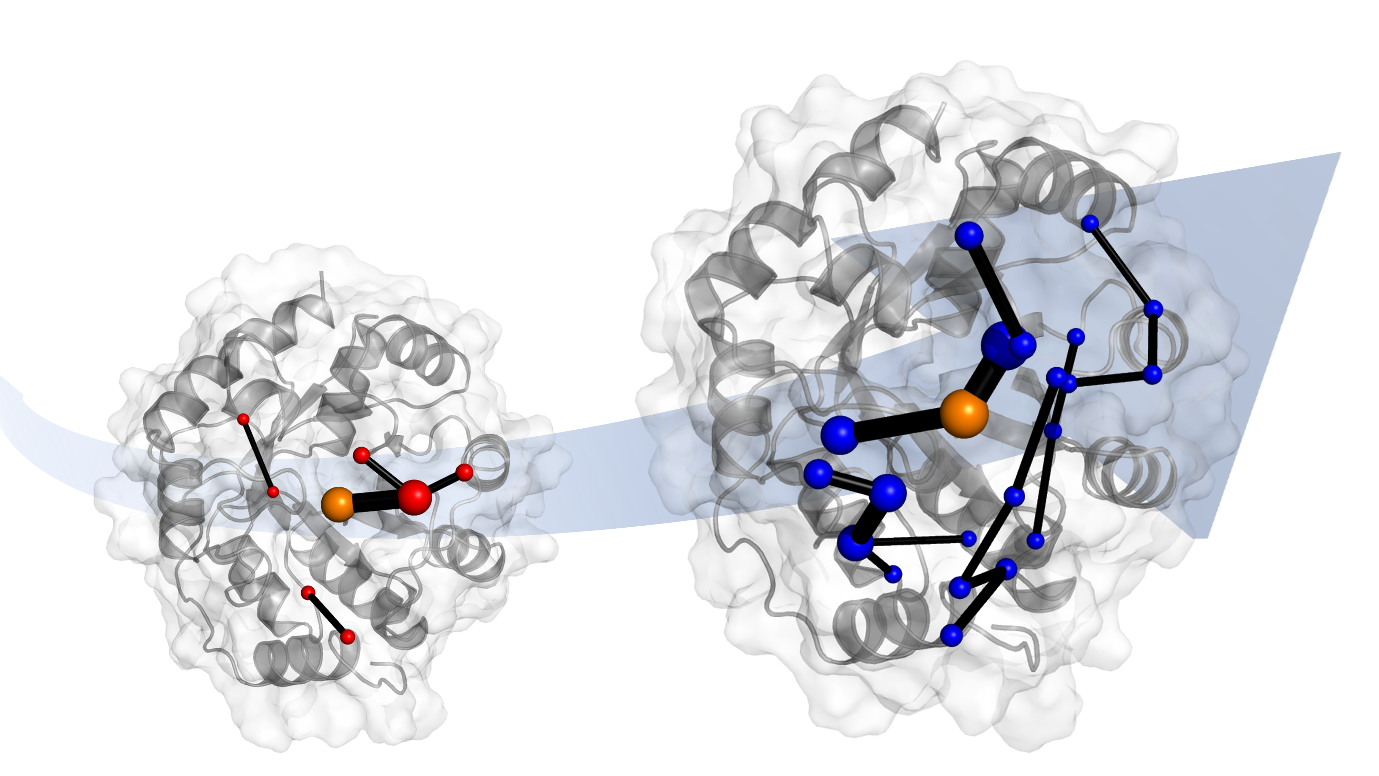

To do so, the international research team from Bristol, the ETH Zurich and the University of Waikato (NZ) turned to molecular computer simulations. “These show that evolution changes the way the protein moves – its dynamics. Put simply, evolution ‘tunes’ the flexibility of the whole protein.”

The team also identified the network of amino acids in the protein responsible for this ‘tuning’. These networks involve parts of the protein that are changed by evolution.

Dr Bunzel remarked: “After evolution, the whole protein seems to work together to accelerate the reaction. This is important because when we design enzymes, we often focus only on the active site only, and forget about the rest of the protein.”

Prof Mulholland added: “This sort of analysis could help to design more effective ‘de novo’ enzymes, for reactions that previously we could not target.”

The research, published in Nature Chemistry, reveals how evolution makes designer enzymes more powerful, paving the way to tailor-made catalysts for green chemistry.

The researchers will now use their findings to help design new protein catalysts.

New Zealand; International

New Zealand; International