Media release

From:

WHO warns of widespread resistance to common antibiotics worldwide

13 October 2025 | Geneva – One in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections causing common infections in people worldwide in 2023 were resistant to antibiotic treatments, according to a new World Health Organization (WHO) report launched today. Between 2018 and 2023, antibiotic resistance rose in over 40% of the monitored antibiotics with an average annual increase of 5-15%.

Data reported to the WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) from over 100 countries cautions that increasing resistance to essential antibiotics poses a growing threat to global health.

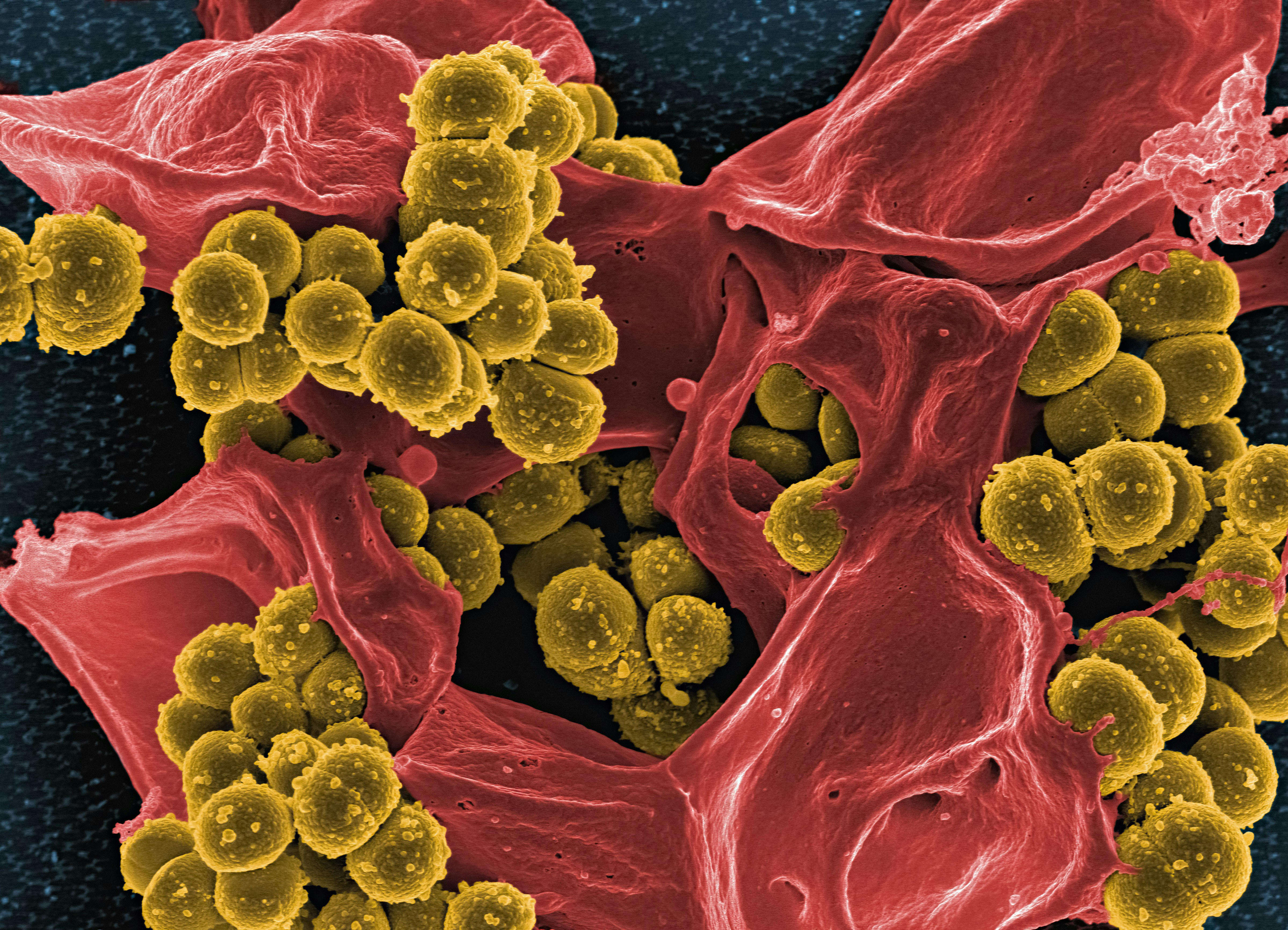

The new Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 presents, for the first time, resistance prevalence estimates across 22 antibiotics used to treat infections of the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, the bloodstream and those used to treat gonorrhoea. The report covers 8 common bacterial pathogens– Acinetobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae — each linked to one or more of these infections.

The risk of antibiotic resistance varies across the world

WHO estimates that antibiotic resistance is highest in the WHO South-East Asian and Eastern Mediterranean Regions, where 1 in 3 reported infections were resistant. In the African Region, 1 in 5 infections was resistant. Resistance is also more common and worsening in places where health systems lack capacity to diagnose or treat bacterial pathogens.

“Antimicrobial resistance is outpacing advances in modern medicine, threatening the health of families worldwide,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “As countries strengthen their AMR surveillance systems, we must use antibiotics responsibly, and make sure everyone has access to the right medicines, quality-assured diagnostics, and vaccines. Our future also depends on strengthening systems to prevent, diagnose and treat infections and on innovating with next-generation antibiotics and rapid point-of-care molecular tests.”

Gram-negative bacterial pathogens are posing the greatest threat

The new report notes that drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are becoming more dangerous worldwide, with the greatest burden falling on countries least equipped to respond. Among these, E. coli and K. pneumoniae are the leading drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria found in bloodstream infections. These are among the most severe bacterial infections that often result in sepsis, organ failure, and death. Yet more than 40% of E. coli and over 55% of K. pneumoniae globally are now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, the first-choice treatment for these infections. In the African Region, resistance even exceeds 70%.

Other essential life-saving antibiotics, including carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, are losing effectiveness against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella, and Acinetobacter. Carbapenem resistance, once rare, is becoming more frequent, narrowing treatment options and forcing reliance on last-resort antibiotics. And such antibiotics are costly, difficult to access, and often unavailable in low- and middle-income countries.

Welcome progress in AMR surveillance—but more action needed

Country participation in GLASS has increased over four-fold, from 25 countries in 2016 to 104 countries in 2023. However, 48% of countries did not report data to GLASS in 2023 and about half of the reporting countries still lacked the systems to generate reliable data. In fact, countries facing the largest challenges lacked the surveillance capacity to assess their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) situation.

The political declaration on AMR adopted at the United Nations General Assembly in 2024 set targets to address AMR through strengthening health systems and working with a ‘One Health’ approach coordinating across human health, animal health, and environmental sectors. To combat the growing challenge of AMR, countries must commit to strengthening laboratory systems and generating reliable surveillance data, especially from underserved areas, to inform treatments and policies.

WHO calls on all countries to report high-quality data on AMR and antimicrobial use to GLASS by 2030. Achieving this target will require concerted action to strengthen the quality, geographic coverage, and sharing of AMR surveillance data to track progress. Countries should scale up coordinated interventions designed to address antimicrobial resistance across all levels of healthcare and ensure that treatment guidelines and essential medicines lists align with local resistance patterns.

The report is accompanied by expanded digital content available in the WHO’s GLASSdashboard, which provides global and regional summaries, country profiles based onunadjusted surveillance coverage and AMR data, and detailed information on antimicrobial use.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Sohinee Sarkar is a Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Anti-Infective Research Unit at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute

Clinicians, Researchers and the World Health Organization have all been warning about the rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) for over a decade. The recent GLASS report provides an important snapshot of the current status of AMR across the world. Despite some critical gaps in data capture, the report has clearly shown the worrying rise in AMR in some of the most common infection types (urogenital, bloodstream and gastrointestinal). Specifically, AMR has increased in 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations that were monitored between 2018 and 2023.

As a researcher working in early-stage drug discovery of new antimicrobials, I am concerned that the GLASS report may only show the tip of the iceberg. Even though countries such as Australia are doing quite well with AMR surveillance and antibiotic stewardship, this is really a global problem that requires more integration of ‘One Health/One world’ measures. Some countries are relying more on the ‘Watch’ category of antibiotics (reserved for infections resistant to first line therapy) to compensate for gaps in diagnostic and surveillance capacity’. Thus, even if a new resistance pattern may emerge in one part of the world, it can easily spread to others with more robust healthcare systems.

Associate Professor Rietie Venter is the Head of Microbiology at the University of South Australia

"The recent WHO report on antimicrobial resistance, based on surveillance data from bacterial infections submitted by 104 countries, raises serious concerns. On average, one in six bacteria exhibited resistance to antibiotics. Particularly alarming are Gram-negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli, which pose significant treatment challenges. The report highlights stark regional differences, with low- and middle-income countries facing the greatest burden. These regions often struggle with limited access to newer or last-line antibiotics, exacerbating the impact of resistant infections. In contrast, Australia is performing relatively well. For example, resistance to carbapenem antibiotics in A. baumannii remains below 3%, significantly lower than the global average of 54.3%.

Overall, the findings underscore the critical importance of:

- Diagnostic tools to inform antibiotic prescription

- Antimicrobial stewardship to ensure responsible prescribing

- Robust and comprehensive surveillance systems to monitor resistance trends

To effectively implement these measures, strategies that strengthen health systems and promote equitable access to antibiotics are essential. Although not explicitly addressed in the report, supporting research and development of new antibiotics or alternative antimicrobial therapies is also vital in combating the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance."

Dr Andreea Molnar is a Senior Lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology.

Associate Professor Andreea Molnar is from the School of Science, Computing and Emerging Technologies at Swinburne University of Technology

"Without effective antibiotics, even routine surgeries could become dangerously risky to perform. The Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 shows a 40% increase in antibiotic resistance for the monitored antibiotics between 2018 and 2023. Approximately one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections were caused by bacteria resistant to antibiotics, with the lowest rate (one in 11) reported in the Western Pacific nations. Although this is positive news for Australia, the rate remains concerningly high, especially given the consequences of antibiotic resistance, such as loss of human lives and increased costs. Given that we live in an interconnected world, a coordinated and a multifaceted approach global effort, tailored to local contexts, is essential to effectively reduce antimicrobial resistance. On a somewhat positive note, the report highlights improvements in surveillance and monitoring, which can help provide a more accurate picture of the situation and support evidence-based decision-making in tackling the issue."

Associate Professor Sanjaya Senanayake is a specialist in Infectious Diseases and Associate Professor of Medicine at The Australian National University

"The Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025 demonstrates that antibiotic resistance remains an enormous problem globally. One positive is that 104 countries are reporting data to a global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) compared to 25 countries in 2016; yet, the completeness of data reported overall was poor (54%). But the bottom line is that between 2108 and 2023, there has been a >40% increase in antibiotic resistance with 1 in 6 infections resistant to antibiotics in 2023. Why does it matter? Because about 5 million deaths were associated with antimicrobial resistance (not just antibiotics, but also antivirals and antifungals). By 2050, this could reach 10 millions deaths a year by 2050 and have a negative impact on global GDP with global losses of USD$100 trillion.

One contributing factor to this can be attributed to antimicrobial use during the pandemic, but the reality is that antimicrobial resistance is such a complex problem. It is not just an issue of doctors prescribing antibiotics inappropriately. Instead, it also includes the vast spectrum of antimicrobial use not just in humans, but also in animals and plants, the use of the unprescribed over-the-counter antibiotics, the contamination of waterways with antibiotics, and the development of new antibiotics. Developing new antibiotics, however, is not cost-effective for businesses, so they require healthy government subsidies to make it attractive for pharmaceutical companies.

The report notes that countries with 'weaker health systems', namely poorer countries, were disproportionately affected by AMR; however, this shouldn't be a source of solace for Australia. Studies show that antibiotic-resistant infections make it across the world through international travel, which has never been as accessible before. Helping poorer countries build better surveillance systems, a One Health approach to animal/human/plant health, research into new vaccines, more rapid and cheaper diagnostics for serious infections, environmental protection of waterways, alternatives to antimicrobials, and governmental support will continue to be vital steps in the silent pandemic that is AMR."

Professor Karin Thursky is Director of the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Melbourne, and Director of the Royal Melbourne Hospital Guidance Group, as well as Associate Director of Health Services Research and Implementation Science, Director of the Centre for Health Services Research in Cancer, Deputy Head of Infectious Diseases and Implementation lead in the National Centre for Infections in Cancer at The Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

"This report is a stark reminder of the real global impact of antimicrobial resistance, but also that there are substantial gaps in data availability from those countries without the infrastructure to support effective surveillance. In Australia, we are in a fortunate situation where our rates of AMR particularly with regards to carbapenems is still very low. With regards to antimicrobial use, Australia has led the world in the surveillance of antimicrobial use appropriateness (using the National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey) and which is much more meaningful than the WHO AWARE criteria. Australian data has shown that the most highly restricted (reserve, or watch) antimicrobials are prescribed pretty well, and it is the ‘Access’ or unrestricted antimicrobials that are being prescribed poorly.

So in fact, setting targets for higher rates of Access antibiotics will not necessarily improve quality of prescribing."

Dr Mark Blaskovich is a Senior Research Officer at the Centre for Superbug Solutions at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at The University of Queensland, and co-founder of the Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery

"This report, based on a global analysis of over 23 million infections confirmed to be caused by bacteria in 104 countries, found that resistance to many essential antibiotics is widespread and increasing. However, the levels of resistance are unevenly distributed, with much higher rates in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, there are large gaps in the report as many countries, particularly some that are known to have high levels of resistance, do not participate in the surveillance. Even those that do often do not have the resources to report all the necessary information. The Western Pacific Region, where Australia is grouped, had one of the lowest reported rates of resistance (9%), but notably only 10 of 27 countries in the region reported data. It is also notable that Australia’s region is situated near the South-East Asia region that has the highest levels of resistance (31%), with transmission via travel a real concern.

Particularly worrying is the finding that some of our more powerful antibiotics are being used more widely than they should be, meaning that resistance to these important antibiotics will continue to develop more quickly than it should, leading to their obsolescence. This leads to the need for new antibiotics, but as outlined in another recent WHO report, the development pipeline for new antibacterial agents is sparsely populated. While Australia is doing relatively well compared to the rest of the world, it must not be complacent and should commit to funding research that combats antibiotic resistance."

Dr Verlaine Timms is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Newcastle

"The WHO’s global report on antibiotic resistance calls for a “One Health” approach linking human, animal, and environmental health. But most of the data still comes from hospitals and clinics, focusing on human infections caused by bacteria like E. coli and Klebsiella. The findings are worrying as resistance continues to rise and treatments are failing.

But there’s a major blind spot. Antibiotic resistance isn’t limited to hospitals, and it doesn’t only spread through harmful bacteria. It can also be carried by harmless microbes found in animals, water, soil, and even within our own bodies. These microbes act as silent carriers, passing resistance genes to more dangerous bacteria. That means they play a critical role in the spread of resistance, even if they don’t cause disease themselves.

By only looking at the microbes that make people sick, we’re ignoring the bigger network that helps resistance spread. The WHO’s Tricycle survey aims to track resistant E. coli across people, animals, and the environment. But most of the data still comes from human health. To truly tackle antibiotic resistance, we need to pay attention to the microbes we usually overlook."

Dr Trent Yarwood is an infectious diseases physician and specialist with the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases

"The Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report is compiled by WHO from over 100 countries, with data on drug-resistant infections. It shows that drug resistance continues to increase around the world, but especially in areas with limited health services. Resistant infection is a major problem in Australia's part of the world - with high rates of resistance in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.

In some parts of the world, one in three infections are resistant to common antibiotics, including second- and third-line treatments. The germs that cause urine and some blood infections can be resistant to antibiotics in more than half of cases globally, and more than two-thirds in some parts of Africa. This means that simple infections - which used to be able to be treated with tablets - now need time in hospital, and in some cases have no effective treatment at all.

Everyone can do something about drug resistance - prevent infections by washing your hands, getting vaccinated and practicing good food safety. Only take antibiotics when they are necessary and only for as long as is recommended by your doctor. This report highlights that we are all connected, so the world needs to work together to help solve the problem."

Anita Williams is a Research Officer in Infectious Disease Epidemiology at The Kids Research Institute Australia

"The findings of the Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 are alarming but not surprising.

Thankfully, the proportion of resistance in Australian children is lower than global averages. In 2022-2023, we found 40% of bacteria causing bloodstream infections in Australian children were resistant to antibiotics, and 1-in-10 bacteria were multi-drug resistant – meaning they’re resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

Whilst globally 45% of E. coli were resistant to 3rd generation cephalosporins, in Australian children it was only 21.5%. For methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA), globally it was 27.1%, whilst in Australian children it was 13.6%.

However, we have observed a rise in the proportion of bacteria in children becoming increasingly resistant to first-line antibiotics. Since 2013, Enterobacterales (such as E. coli) resistant to co-trimoxazole has increased from 16.9% to 24.8%, and resistance to augmentin has increased from 4.2% to 12.8%. These antibiotics are common first-line treatment for urinary tract infections in children.

Although lower than reported globally, these numbers still represent a significant risk to paediatric healthcare in Australia. In order to protect our children, it is vital that we continue to improve surveillance efforts and fund epidemiological research into the drivers of antimicrobial resistance in Australia and beyond."

James Graham is Chief Executive Officer at Recce Pharmaceuticals Ltd

“The World Health Organization’s latest report is a stark reminder that antimicrobial resistance is rising faster than our ability to respond, and the pipeline of new antibiotics to counter this threat has all but run dry. Most antibiotic classes we rely on today were discovered between the 1940s and 1980s, and no new class has been approved in over 40 years.

This innovation gap is colliding with escalating global resistance, leaving doctors with fewer options and patients at greater risk. Infections that were once easily treated now mean longer hospital stays, higher treatment costs, and, in some cases, preventable amputations such as those seen in diabetic foot infections.

Next-generation novel approaches are urgently needed to stay ahead of this crisis.

Australia has a proud history of medical breakthroughs - Howard Florey led the team that transformed penicillin from a laboratory curiosity into the world’s first widely used antibiotic, a discovery that revolutionised medicine and saved millions of lives. Today, new technologies are emerging to rebuild the depleted antibiotic pipeline.

Recognised by WHO among antibacterial products in clinical development, these compounds offer new hope in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the defining health challenges of our time, addressing it demands innovation on a global scale.”

Australia; International

Australia; International