News release

From:

Kiwis Show High Trust in Scientists – Global Study

Aotearoa New Zealand ranks 9th in the world for trusting scientists, according to an international study published this week in Nature Human Behaviour.

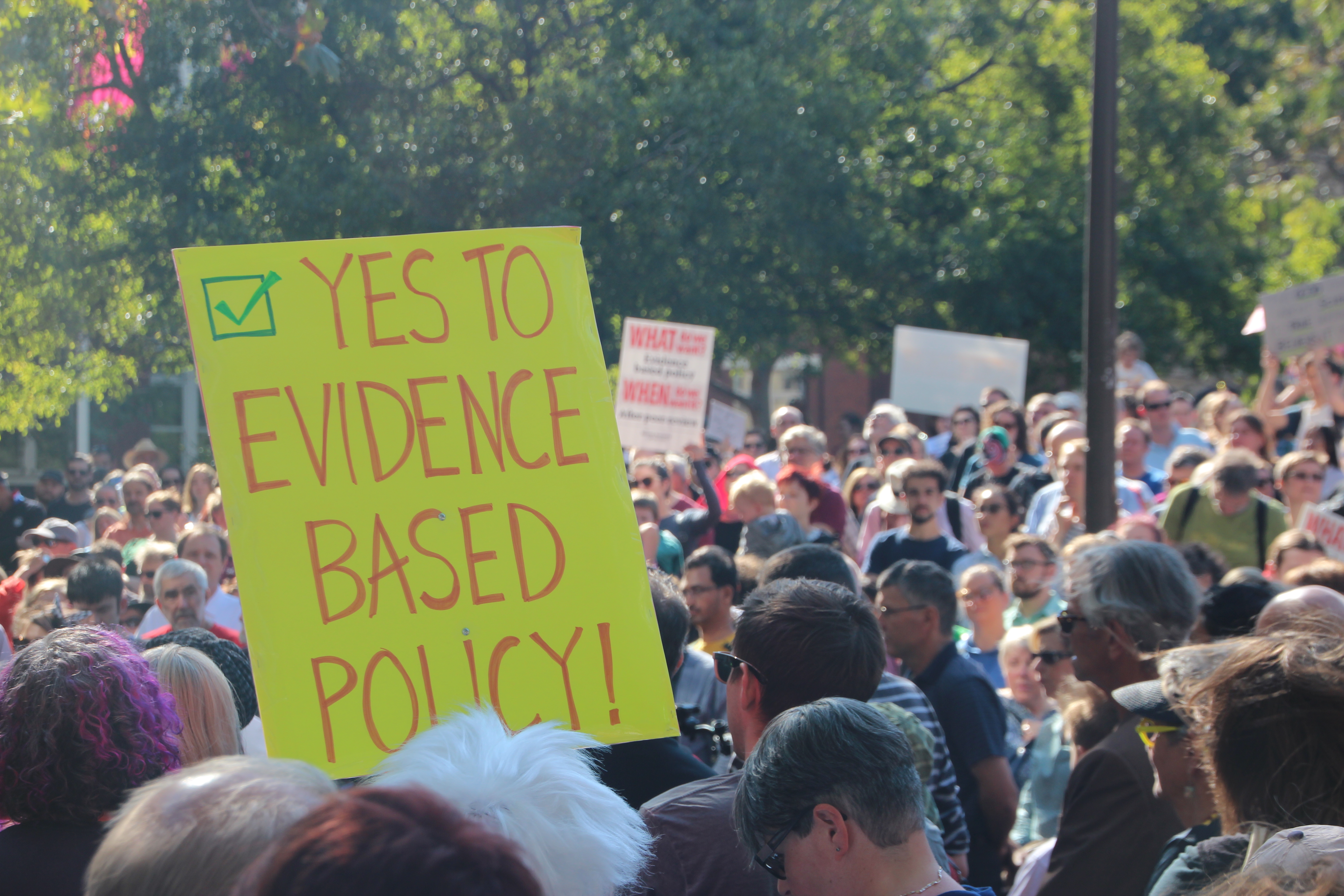

Despite widespread claims of a “crisis of trust” in science, a global study finds that most people hold relatively high levels of trust in scientists. Most people in both Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) and overseas also believe that scientists should play a greater role in society and policymaking.

“These findings confirm that the NZ public trusts scientists and believes scientists should work with politicians to inform policymaking, which aligns with the current government’s commitment to evidence-based decisions,” affirms NZ co-author Prof Taciano Milfont from the University of Waikato’s School of Psychological and Social Sciences.

The study, part of the TISP Many Labs initiative, surveyed over 70,000 people across 68 countries, including 2000 New Zealanders, offers unprecedented insights into public attitudes toward science. Globally, the results reveal that trust in scientists is high, with an average trust level of 3.62 on a scale from 1 (very low trust) to 5 (very high trust).

How New Zealand compares to Other Countries

While respondents in Albania, Kazakhstan and Bolivia had the lowest levels of trust in scientists, those in Egypt had the highest levels of trust globally with a 4.30 score, followed by respondents in India and Nigeria.

In New Zealand, the mean trust level was 3.88, placing the country 9th overall and behind Australia placed 5th with a 3.91 score. Australian and NZ respondents, along with those from the United States, United Kingdom and China, had higher-than-average trust in scientists, whereas respondents in Germany, Hong Kong and Japan had lower-than-average trust.

“This is the largest global study conducted on trust in science since the Covid-19 Pandemic,” says co-author Gina Grimshaw of the School of Psychology at Victoria University of Wellington.

“The pandemic brought scientific information - and misinformation - into our daily lives as it had not been before. Many of the issues it raised, such as health behaviours, isolation, and vaccination became contentious issues. Despite some very vocal criticisms of science and science-led policies during the pandemic, trust in the broader population remains high”.

Scientists Expected to Engage

The study also asked New Zealanders about the role scientists should play in society and politics. An overwhelming 79% of New Zealand respondents agreed that scientists need to communicate their work to the public. Additionally, 62% agreed that scientists should work closely with policymakers to integrate scientific findings into decision-making.

These findings show that New Zealanders expect scientists to take an active role in sharing and applying their findings. “Science communication tends to be more effective when scientists engage in meaningful dialogue and discussion with the communities they work alongside,” says co-author Laura Kranz from the School of Science in Society at Victoria University of Wellington.

“Scientists should seek to not simply just share their findings, but actively listen and be responsive to the voices and views of New Zealanders”.

Public Health, Energy, and Poverty as Top Science Priorities

When asked about the goals science should prioritise, most New Zealanders agreed that research should focus on improving public health (84%), solving energy challenges (76%), and reducing poverty (66%). However, fewer respondents felt that science currently prioritises these areas (65%, 62%, and 38%, respectively, strongly or very strongly believed that science aims to tackle these goals).

“These results show the New Zealand public expects scientists to focus on tackling the big challenges that affect society” says Dr John Kerr, a further New Zealand co-author and Senior Research Fellow in Public Health at the University of Otago, Wellington. “It is important not only for scientists to hear this, but also for the wider science system—including those who make decisions about which scientific research gets prioritised and funded.”

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Professor Sujatha Raman, UNESCO Chair-holder in Science Communication for the Public Good, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science (CPAS), ANU

The paper embodies exactly the kind of thing we expect to see in high-quality scientific work:

- Bringing nuance to a topic characterised by headlines such as which countries rank highly in measure of trust in science or how a supposed decline of trust is the cause of all manner of problems;

- Bringing balance by exploring the limitations of their study;

- Taking care to point out what doesn’t follow from their study.

So yes, they find trust in science is higher than we might expect from recent headlines and that this holds in most countries. But they point out the bias towards more educated groups in their sampling in global South countries. People are also likely to have different ideas of who is or isn’t a scientist when they answer these survey questions; their survey does not get into these differences as they acknowledge.

Most importantly, we should be thinking harder about what it means if somebody says they trust science or scientists. This paper suggests that such an expression of trust is simply the starting point for enhancing science/society engagement. People expect scientists to consider their priorities and work towards the public good. Trust in this sense has to be consistently earned, not taken as a given.

Second, I would have liked to have seen some discussion on the role of scientists in wading through and helping the public make sense of and assess diverse – often conflicting - bodies of scientific knowledge. This would involve much more than fact-checking. It would call for contextual nuance and balanced reasoning. Perhaps this is the next stage in building trustworthy relations between science and society

Dr Omid Ghasemi is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk & Response and is one of the co-authors of the paper

This study brings encouraging news, highlighting high global trust in scientists and strong support for their role in policymaking. Australia and New Zealand stand out for their particularly positive attitudes, with a notably smaller gap between what the public perceives as scientists’ priorities and what they believe those priorities should be.

However, the findings also raise important concerns. In some countries, political orientation is associated with lower trust in scientists, which might worsen with increasing partisan divides. Additionally, younger individuals exhibit lower trust levels compared to older generations. While these issues are less pronounced in Australia and New Zealand, it remains essential to develop targeted strategies to sustain and strengthen trust across political groups and generations.

Dr Susannah Eliott is the CEO of the Australian Science Media Centre

It is great to see that trust in scientists remains high in most countries. But scientists mustn't be complacent. The information landscape is changing dramatically and it would be good if this kind of study could be used as a benchmark and repeated every 3-5 years to see how trust changes over time. The data in the current study was collected just as ChatGPT was being rolled out across the world and before some of the technology that makes it easy for anyone to create deepfake images and videos was made widely available.

As mis and disinformation continue to evolve, there will be those who seek to make use of this trust for their own benefit (scientists can be "made" to say anything using deepfake technology - e.g. the unsolicited use of Dr Karl's voice and image to sell products online). Transparency and the reliability of sources will become even more important in maintaining trust.

For scientists, becoming more involved in policymaking and having open and meaningful dialogue with the public is no small feat. The institutions that employ researchers will need to try and ensure that their scientists are protected from the kind of online abuse that can come from any kind of advocacy.

Kylie Walker is Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences & Engineering (ATSE)

At a time when misinformation and disinformation are proliferating it’s both heartening and important that trust in science and scientists remains high. As we tackle complex challenges and global change, the place of evidence informed policy- and decision-making is paramount. The Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (ATSE) is proud to work with our Fellows - leading applied scientists, technologists and engineers - to bring the best available evidence to inform and advise senior Australian decision-makers and policy-makers, and the public.

Ryan Winn is the Chief Executive Officer at Science and Technology Australia

This study highlights the strong trust Australians have in science and scientists, and that people see the crucial importance of using that science to inform and guide policymaking. Indeed, the majority of people want scientists to be more closely involved in policymaking.

The imminent Federal election provides an opportunity to powerfully leverage science and the nation’s scientists to fuel policy and future jobs. STA’s comprehensive suite of election asks would secure the nation’s economy into the future - an economy powered by Australian ingenuity.

Australia’s investment in research and development, as a percentage of R&D, languishes nearly 40% lower than the OECD average. The politicians and parties standing for election can put us back on the path the public wants by committing to an Innovation Future Fund; a Strategic Moonshot Program; and a robust strategy to increase Australia’s R&D investment to 3% of GDP.

Professor Melissa Brown is President of the Australian Council of Deans of Science (ACDS) and Executive Dean of the Faculty of Science at the University of Queensland

Public trust in science is essential for empowering our communities and governments to make evidence-based decisions, to ensure the outcomes of scientific research are accepted and embraced by end-users, and to foster the social license of scientists to operate in public institutions.

As the President of the Australian Council of Deans of Science, representing Deans of Science or equivalent in 35 Australian universities, I was delighted to read the article by Viktoria Cologna and >200 colleagues, who generate a comprehensive data set from a broad international survey and provide significant insights into global trust in scientists.

Whilst it was good to see that globally, and particularly in Australia, trust in scientists is moderately high (3.62/5 globally, 3.91/5 Australia), this also suggests that there is room for improvement.

The analysis shows interesting variations between countries and associations with some demographics and country level indicators. The most important outcomes from this work from my perspective however were the strong view of respondents that scientists should work more closely with politicians in policymaking and the very strong view that scientists should communicate science to the general public. The perceived and desired scientific research priorities were also thought-provoking.

This publication should provide food for thought for universities, including how they should engage with government to develop a shared understanding of the value of scientists and their potential to contribute to policy development, and how they communicate research priorities and outcomes to their communities.

Dr Cathy Foley is former Chief Scientist of Australia AO PMS

Too often we see a headline that says the community does not trust science. This comprehensive study provides clear evidence that this is not the case globally but especially in Australia where we rank 5th in the world for trust in scientists. This does not surprise me as my experience of the Australian science and research sector is overwhelmingly one of high integrity and passion to see science undertaken for the betterment of society.

But while there is trust in scientists, there is an expectation that we communicate our work more broadly in dialogue with the community and that scientists be involved in policy development. When I was Australia’s Chief Scientist, I found that governments were keen to have the evidence to assist with policy development. I am glad to see the evidence stacks up.

It is interesting that in Australia there is always an economist in the room for policy development. Scientists are only occasionally included. Should this change?

There is also a message that scientists need to be more open about where our funding comes from and our data sources too. Generally communication of science to the public but via a genuine dialogue – not I told you approach – was valued.

Note that this study did not differentiate between different science disciplines. There was a study recently that indicated there was variation in trust in the science across different disciplines.

Mark Alfano is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Macquarie University

We found that trust in science is generally high all around the globe, but it lags in certain populations, especially in post-Soviet states, countries with high economic inequality, and among individuals who adopt a worldview that prioritises social dominance hierarchies. To me, this suggests that, to the extent that we face a crisis of trust, it is not a problem that can be solved by improving science or science communication. Instead, we need to improve the political economy of our societies so that it becomes more natural for people to trust institutions that are already, to a large extent, trustworthy.

Dr Robert Ross is a Research Fellow in the School of Humanities, Ethics and Agency Research Centre at Macquarie University. Robert is a co-author on the paper

A very positive finding from this research is that Australians had the fifth highest level of trust in scientists out of the 68 countries that were studied, and New Zealanders weren’t far behind at ninth.

Dr Mathew Marques is a Senior Lecturer in Social Psychology at La Trobe University, Melbourne

This is the largest ever global study of trust in science and scientists, involving a team of 241 researchers who surveyed almost 72,000 participants across 68 countries. It comes on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic, where some were vocal against scientists and science-led decision-making. Counter to narratives of a “crisis of trust” in science, our findings reveal most people worldwide have relatively high trust in scientists and want them to be more involved in society and policymaking.

Locally, Australia ranked fifth highest in trust in scientists scoring significantly above the global average. There were surprisingly few differences in trust across demographics, with no differences in age or gender, and small positive associations with income and education. Unlike North America and many Western European countries, in Australia having a conservative versus liberal political orientation was not associated with trust. This could mean political polarisation around science is not as much of an issue as it is for specific scientific issues, like climate change.

While viewed as highly competent, with moderate integrity and benevolent intentions, there is a perception that scientists are less open to feedback. We recommend scientists take these results seriously. They should find ways to be more receptive to feedback and open to dialogue with the public.

Associate Professor Fabien Medvecky, Associate Director - Research, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science (CPAS), The Australian National University, comments:

The current study “Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries” is probably the broadest and most robust work I’ve seen that addresses the issue of trust in science, and especially trust in scientists across the globe.

"After surveying nearly 72,000 people across 68 countries, here are the things that stand out. Firstly, there is not one country that shows low levels of trust in science. But there is variation across countries. Egypt and India have, by far, the highest trust in science but the Antipodean countries also show very high levels of trust. Australia ranks 5th and New Zealand 9th in overall trust in scientists (US=12th, UK=15th).

"More interesting is that many of the stories we hear about leads to (dis)trust are challenged when we take a broader, more robust look. Religiosity (often used as an example of anti-science, especially in the US) is in fact positively correlated with trust in science on a global level. Conversely, science literacy has almost no effect on trust in science.

"The study also looks at how scientists should engage with society. Most people across the globe think scientists should contribute to public debates and policymaking (~50-55% for, ~25% neutral, and ~25% against), but the strongest call by far is for more science communication with a whopping 83% of people thinking scientists should communicate to the general public about their work.

"If there are any major lessons for New Zealand, it’s that our privileged position of high trust in science and scientists is likely going to worsen if government continues to strip funding for social science as these are what underpins effective science communication.

Australia; New Zealand; International; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; ACT

Australia; New Zealand; International; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; ACT