Media release

From:

In a discovery that could reshape how we think about memory, researchers at Flinders University have found that forgetting is not just a glitch in the brain but is actually a finely tuned process, and dopamine is the key.

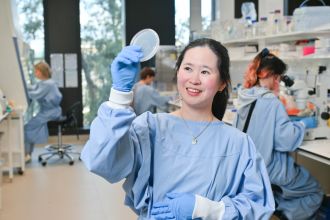

Led by neuroscientist Dr Yee Lian Chewand PhD student Anna McMillen, from Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute (FHMRI), the research team has shown that the brain actively forgets using the same chemical that helps us learn, dopamine.

Published in the Journal of Neurochemistry, the study used tiny worms called Caenorhabditis elegans – one millimetre long with only 300 neurons, yet 80% genetically identical to humans – to explore how memories fade.

These microscopic creatures might seem worlds apart from humans, but their brains share many of the same molecular pathways that makes them perfect for studying brain pathways including memory.

The researchers from FHMRI’s Worm Neuroscience Laboratory trained the worms to associate a specific scent with food, then observed how long the memory of that association lasted.

Surprisingly, worms that could not produce dopamine held onto the memory much longer than normal worms. In other words, without dopamine, they took much longer to forget.

Dr Chew explains, “We often think of forgetting as a failure, but it’s actually essential. If we remembered everything, our brains would be overwhelmed. Forgetting helps us stay focused and flexible.”

The team also discovered that two specific dopamine receptors—DOP-2 and DOP-3— which are similar to some dopamine receptors found in humans, work together to control forgetting. When both were disabled, the worms clung to their memories just like the dopamine-deficient ones.

Even when the researchers tried to restore dopamine in certain brain cells, it was not enough because the whole dopamine system needs to be working for forgetting to happen properly.

“We found that dopamine receptors in the worm that are similar to those found in humans play a role in regulating this forgetting behaviour,” she says.

“We use the worm brain to understand these chemical changes, hoping that we can translate our research on the tiny worm brain to the much bigger brain of humans.

“This research could help us understand human memory because dopamine plays a major role in conditions like Parkinson’s disease, where memory and learning can be affected.

“We are now trying to identify exactly how dopamine acts on neurons in the brain to ‘forget’ old memories.

“We think this may have implications for gradual memory loss during healthy ageing, or in dopamine-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

“By understanding how dopamine helps the brain let go of memories, we may one day find new ways to support people with memory-related disorders.”

The research builds on similar findings in fruit flies, suggesting that dopamine-driven forgetting is a universal brain function.

“It’s exciting to see that something so fundamental is shared across species,” she says.

“It means we’re tapping into a deep biological truth which helps us lay the groundwork for breakthroughs in human health."

The paper, ‘Dopaminergic Modulation of Short-Term Associative Memory in Caenorhabditis elegans’, by Anna McMillen, Caitlin Minervini, Renee Green, Michaela E. Johnson, Radwan Ansaar and Yee Lian Chew was first published in Journal of Neurochemistry on 19 August 2025. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.70200

Acknowledgements: A.M. is funded by a Flinders University Research Scholarship (Flinders University). Y.L.C. is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (GNT1173448), the Flinders University Parental Leave Research Support Scheme, the Flinders University Impact Seed Funding Grant for Early Career Researchers and the Flinders Foundation Mary Overton Senior Research Fellowship.

Multimedia

Australia; SA

Australia; SA