News release

From:

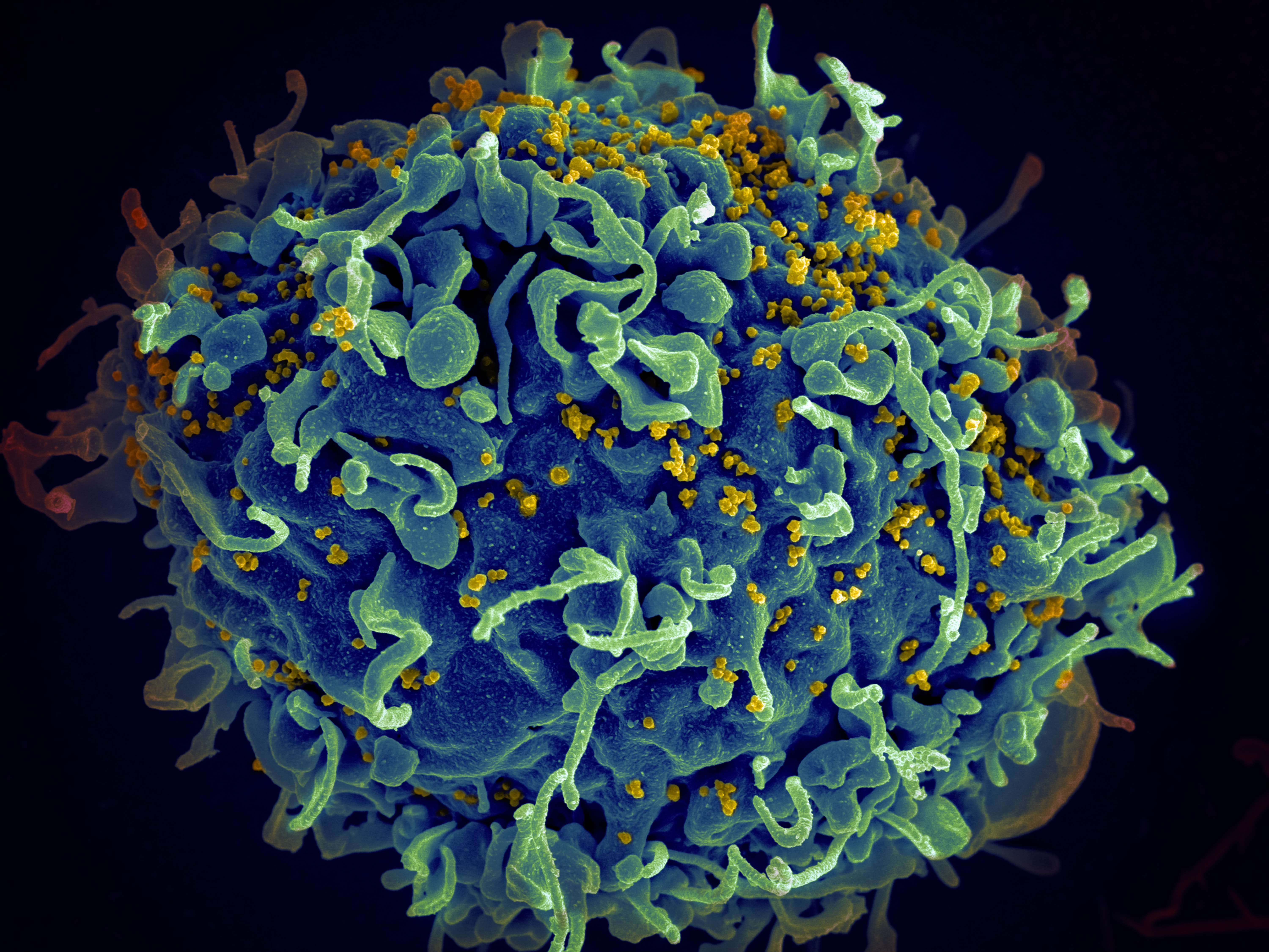

Medicine: Sustained HIV-1 remission after stem cell transplantation

A recipient of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant to treat leukemia has shown persistent suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) more than 9 years after the transplantation and 4 years after the suspension of anti-retroviral therapy. The results are reported in Nature Medicine this week.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a procedure used to treat certain cancers, such as leukemia, by transferring immature blood cells from a donor to repopulate the bone marrow of the recipient. CCR5Δ32/Δ32 HSCT involves the transfer of cells from a donor with two copies of the Δ32 mutation in the gene encoding the HIV-1 co-receptor CCR5; such cells are resistant to HIV-1 infection. So far there have been two published cases of patients experiencing remission of HIV-1 after cancer treatment involving the transplantation of CR5Δ32/Δ32 hematopoietic stem cells: the ‘London patient’ and the ‘Berlin patient’.

Björn-Erik Jensen and colleagues now present a detailed longitudinal analysis of blood and tissue samples from a patient demonstrating remission of both leukemia and of detectable HIV-1 after transplantation of CR5Δ32/Δ32 hematopoietic stem cells. The patient, a 53-year-old male, was diagnosed as having acute myeloid leukemia in January 2011. The patient underwent transplantation of CR5Δ32/Δ32 stem cells from a female donor in February 2013, followed by chemotherapy and infusions of donor lymphocytes. After the transplantation, anti-retroviral therapy was continued, but pro-viral HIV-1 was undetectable in the patient’s blood cells. Anti-retroviral therapy was suspended in November 2018 with the patient’s informed consent, almost 6 years after the stem cell transplantation, to determine whether infectious HIV-1 persisted in the patient. The authors did not observe a resurgence of HIV-1 RNA or a boosting of the immune response to HIV-1 proteins that might have suggested a lingering, yet undetectable, viral reservoir 4 years after the suspension of anti-retroviral treatment.

The authors conclude that although HSCT remains a high-risk procedure that is at present an option only for some people living with both HIV-1 and hematological cancers, these results may inform future strategies for achieving long-term remission of HIV-1.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Ioannis Jason Limnios is from the Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine at Bond University

During the pandemic, the public learned that viruses use special "door handles" called receptors to get into our cells. Just as COVID-19 uses the ACE-2 receptor to infect cells of the lungs and other tissues, HIV uses a different receptor called CCR5 to infect cells of the immune system. What happens if the door handle is missing? For about 30 years it has been known that some individuals are resistant to HIV infection because they lack CCR5 receptors on their cells; HIV can’t open the door and get inside.

This study shows that transplanting blood stem cells from an HIV-resistant donor has led to the development of a new, HIV-resistant immune system in an HIV+ patient. By following the patient for a decade after transplantation, researchers have shown that their HIV resistant immune system is stable and working well, and that the patient remains healthy after stopping antiviral therapy for 4-years.

Over the past 10 years, stem cell and gene editing technologies (such as CRISPR) have advanced medical science to a point where we can now engineer stem cells for such therapies. Rather than harvesting stem cells from donors with rare and special genetics, they can be created in specialised facilities under highly controlled conditions, and in greater quantities.

This is important and exciting progress in the fight against AIDS, however the researchers carefully state that HIV remains hidden in other tissues of the body. So, it’s not yet clear if type of therapy is a life-long “cure,” and the risk of passing on HIV, whilst extremely low, will never be zero using this therapy alone.

International; QLD

International; QLD