Media release

From:

Peer-reviewed Observational study Animals

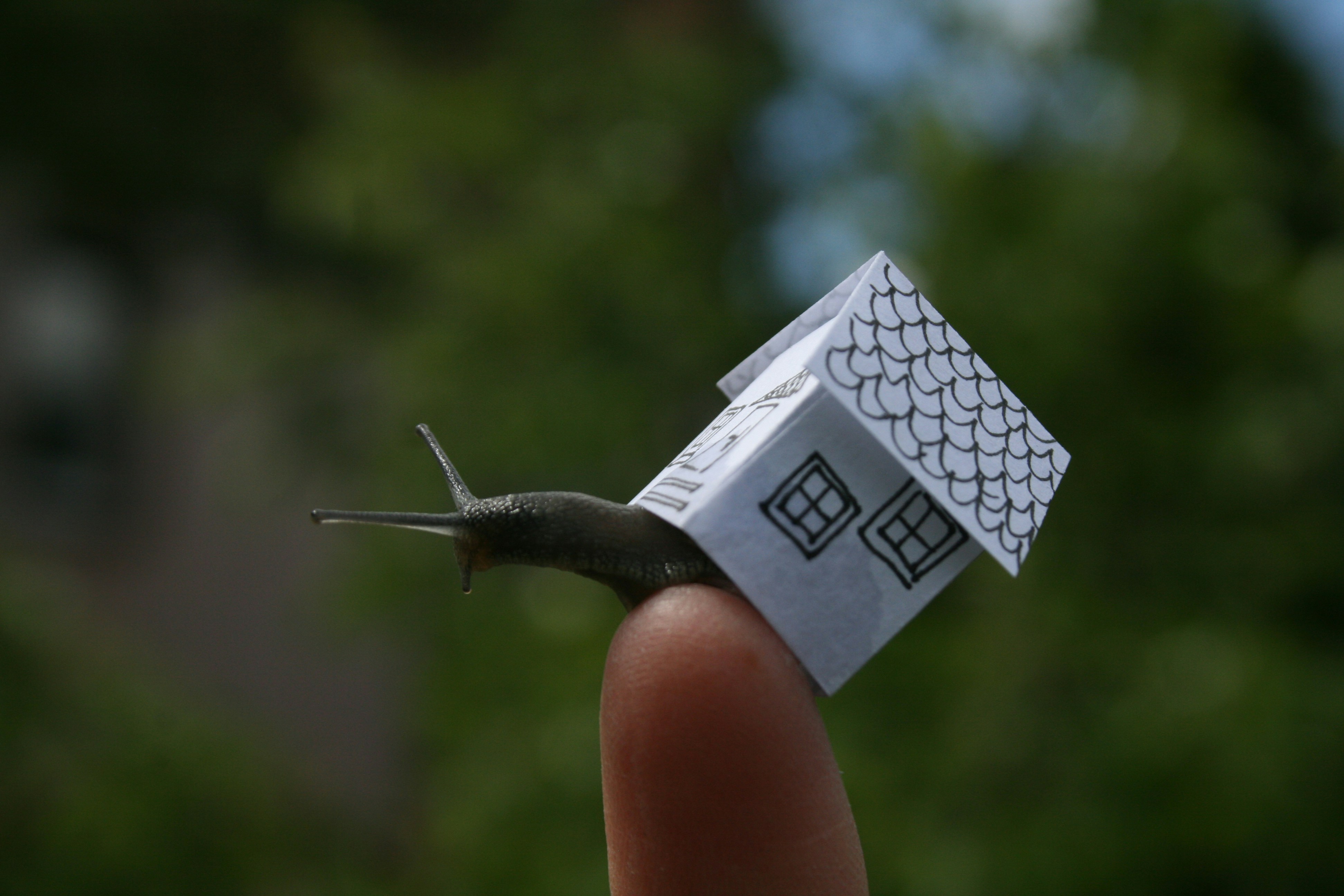

Slugs and snails love the city, unlike other animals

Analysis of crowd-sourced data reveals species’ tolerance of urban habitats in Los Angeles

Most native species avoid more urbanized areas of Los Angeles, but slugs and snails may actually prefer these environments, according to a study publishing May 29 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Joseph Curti from the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

Urban areas continue to grow around the world, putting pressure on native species that find it difficult to tolerate the habitat changes and pollution it brings. To conserve and even increase biodiversity in cities, scientists and city planners need large-scale data on the ecological communities present, but this is time consuming and difficult to collect. Researchers used data from iNaturalist, a large database of species observations contributed by scientists and community scientists, to investigate the tolerance of animal species to urban environments. They calculated an urban tolerance score for 512 terrestrial animal species native to southern California. Species were divided into taxonomic groupings including mammals, reptiles and amphibians, birds, butterflies and moths, spiders, bees and wasps, and slugs and snails, among others. Next, they assessed the occurrence of urban-tolerant and intolerant species across a grid of squares covering Los Angeles. They combined this with data on the level of urbanization in different grid cells across the city, such as light and noise pollution.

On average, native species preferred less urbanized locations. Snails and slugs were the exception — the five mollusk species included in the study were more common in more urbanized areas. Butterflies and moths, on the other hand, were the least urban-tolerant group. Mammals and reptiles and amphibians were also relatively intolerant of urban environments, while lady beetles, spiders and birds had less strong preferences – though still preferred less urbanized areas overall.

The analysis could help city planners to increase urban biodiversity. For example, butterfly observations could be used to identify target locations for conservation initiatives to support endangered species like the Palos Verdes blue butterfly. The study also provides baseline data to assess the success of local biodiversity initiatives. Although crowd-sourced data has limitations, for example because not all species are easy for members of the public to detect, the authors note that it can also provide a rich database to help manage and promote biodiversity in cities.

The authors add: “In collaboration with the City of Los Angeles, we sought to understand how native species were distributed across the city and to describe their association with urban intensity. We found that native species in Los Angeles were on average negatively associated with urban intensity, and that areas of the city with higher urban intensity typically contained more urban tolerant native species. The methodology developed for this research project is intended to be reevaluated in order to track efforts to increase urban native species within the City of Los Angeles.”

International

International