Media release

From:

Slingshot spiders listen to fire off ballistic webs when they hear mosquitoes within range

Brief Summary: Slingshot spiders (Theridiosoma gemmosum) pull the centre of their web back creating a cone which they release, catapulting forward, to capture passing insects. Now researchers from The University of Akron, USA, have discovered that the spiders listen for passing prey and when an insect is within range, they release the web to capture the victim, even before the insect has blundered into it, like a Roman fisherman gladiator flinging his weighed net at an opponent.

Press release: Armed with a net and trident, fisherman gladiators were a staple of Rome’s gladiatorial games. Their best chance of survival was to quickly entangle a heavily armed opponent with their weighted net. Remarkably, some spiders use much the same strategy. Slingshot, or ray spiders (Theridiosoma gemmosum) pull the centre of their flat web back, to form a cone with the spider at the tip, keeping the net in place by holding on to a taut anchor thread. They release this thread to let the web fly, catapulting it forward when an insect passes by to ensnare the victim in the web’s sticky spiral. However, Saad Bahmla (Georgia Institute of Technology, USA) and colleagues, including Todd Blackledge (University of Akron, USA), discovered in 2021 that they could trick the wily arachnids into releasing their ballistic nets by simply clicking their fingers. Might the weapon-wielding spiders be listening to deploy their webs even before their victims have blundered into them? Sarah Han, also from the University of Akron, and Blackledge decided to test the spiders’ reactions. They publish their discovery in Journal of Experimental Biology that slingshot spiders are capable of listening for approaching insects, waiting for their victim to get within range before releasing the web to catapult forward and capture their next meal.

‘Slingshot spiders are really tiny, so they can be quite hard to find’, recalls Han, who spent a lot of time on local riverbanks peering into crevices and rocks for the distinctive cone-shaped webs with a spider perched at the tip. ‘It does take some time to develop the eye for them’, she chuckles. After rehoming the spiders in the lab with twigs to build their webs upon, Han also went hunting for mosquitoes, ready to tempt the spiders. She then attached individual flies – with their wings free to flap as if flying past – to strips of black paper before waving them close to the spiders’ cone-shaped webs while filming.

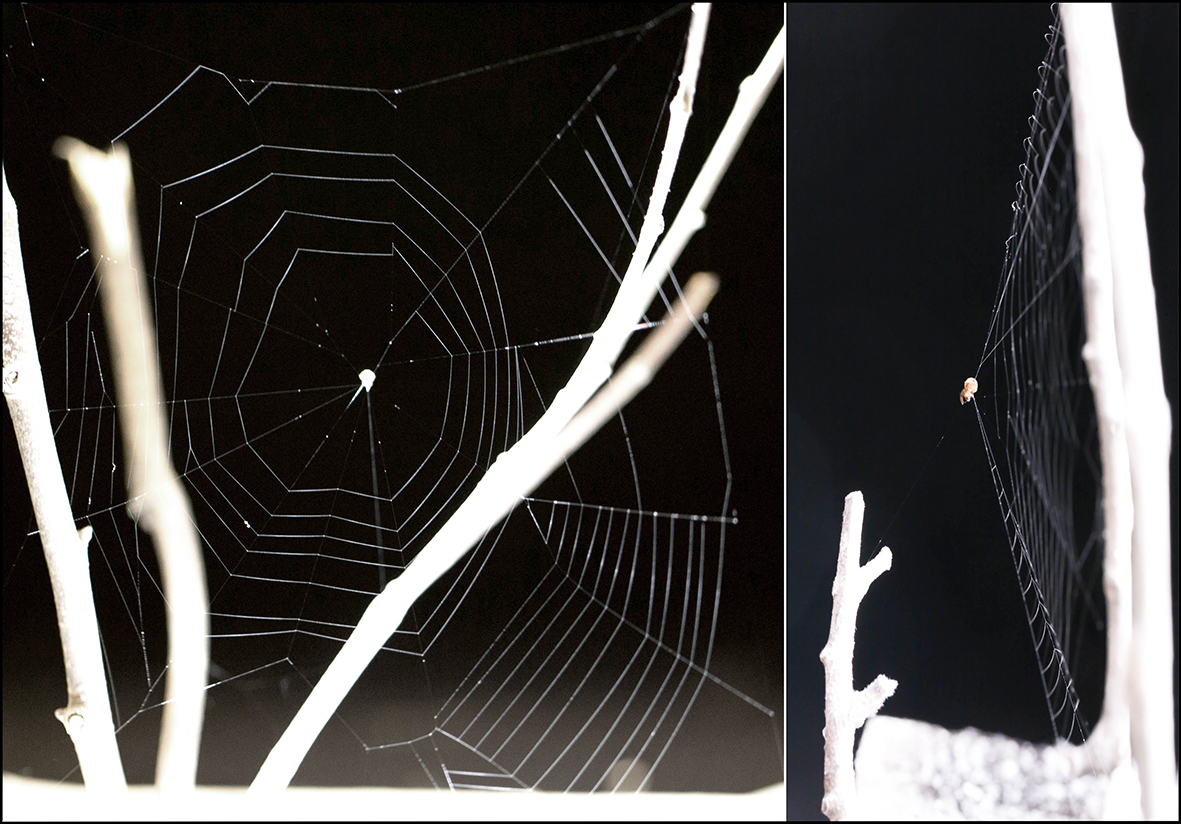

Two views of a slingshot spider (Theridiosoma gemmosum) web; the right image shows the web’s cone shape with a spider at the tip.

Sure enough, the spiders let loose their webs when the flapping mosquitoes were in the vicinity. But when Han took a closer look at the movies they had recorded, it was evident that the insects never touched the webs with their protruding front legs. The spiders were capable of launching the structures even before an insect impacted the web. And when Han tried the same trick, but this time waving a tuning fork, pitched at the tone produced by the flies’ whining wings, in front of the web, the arachnids still released their webs to rocket forward. The spiders must have been listening for the approaching insects, letting loose their webs when the mosquitoes were in range, before the insect had blundered into it. Han and Blackledge suspect that the spiders could be listening for the mosquitoes’ approach with sound-sensitive hairs on the arachnids’ legs.

And how fast did the webs fly once the spiders let go? Han meticulously plotted each spider’s trajectory as they rode the web while it ripped forward and calculated that the structures accelerate at up to 50g (504m/s2) reaching speeds of nearly 1m/s to intercept a mosquito within 38ms: far too fast for the insect to make an escape. Han also noticed that the spiders were much more likely (76%) to release their web cones when the mosquito was in front of the web, rather than the occasions when it was behind (29%), and the duo suspects that the spiders may compare how they perceive sound transmitted through the web to their bodies with the sound vibrations carried through the air to their legs, to tell them whether an insect victim is in front of or behind their web, to avoid a misfire.

Multimedia

International

International