News release

From:

Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

A plume of upper-atmospheric lithium pollution observed in February 2025 has been attributed to the re-entry of a specific rocket stage. The results, published in Communications Earth & Environment, are the first known instance of the direct detection of upper-atmospheric pollution from space debris re-entry.

Defunct satellites and expended rocket stages are designed to break up during their atmospheric re-entry. Previous research has focused on the risks of debris reaching the ground, but little is known about the effects that disintegrating space debris might have on the mesosphere (between approximately 50 and 85 kilometres above sea level) and the lower thermosphere (between approximately 85 and 120 kilometres above sea level).

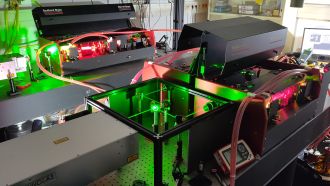

Robin Wing and colleagues measured the concentration of lithium atoms in the lower thermosphere using a lidar — a laser-based remote sensing instrument used to measure atmospheric conditions — located in northern Germany. Lithium is widely used in spacecraft components but is found naturally at these heights only in trace amounts. Shortly after 00:20 UTC on 20 February 2025, the authors detected a sudden increase in the concentration of lithium atoms to 10 times the baseline value. This lithium plume stretched from 97 kilometres above sea level down to 94, and was observed by the authors for the next 27 minutes until data recording stopped.

The authors used atmospheric wind models to calculate the path and potential origin of the lithium plume. They found that the most likely area of origin was on the path of a Falcon 9 upper stage that had re-entered the atmosphere uncontrolled over the Atlantic Ocean, west of Ireland, about 20 hours earlier. Additional calculations demonstrated that natural atmospheric processes were highly unlikely to be the source of the plume.

The authors note that their paper presents a case study of the pollution caused by a single piece of space debris, while also demonstrating a method for measuring such pollution. They warn that not all released material can be measured this way due to chemical changes which occur during descent. The authors argue that further observations and atmospheric chemistry modelling will be needed to understand how these pollutants might affect the atmosphere long-term, but caution that the amount of upper atmosphere pollution is likely to increase given the substantial rise in orbital launches over the last decade.

Multimedia

International

International