Media release

From:

Professor Jenny Gunton heads the Centre for Diabetes, Obesity and Endocrinology Research at The Westmead Institute for Medical Research (WIMR) and led this study with PhD student Dr Linda Wu.

Professor Gunton says that identifying those who are at high risk of developing checkpoint inhibitor-associated autoimmune diabetes (CIADM) would allow for earlier and closer monitoring and potentially reduce the number of people presenting with serious complications like diabetic ketoacidosis.

What is immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a type of immunotherapy, used to treat cancers like melanoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma. They are most commonly used in treating cancer that has spread (metastatic cancer).

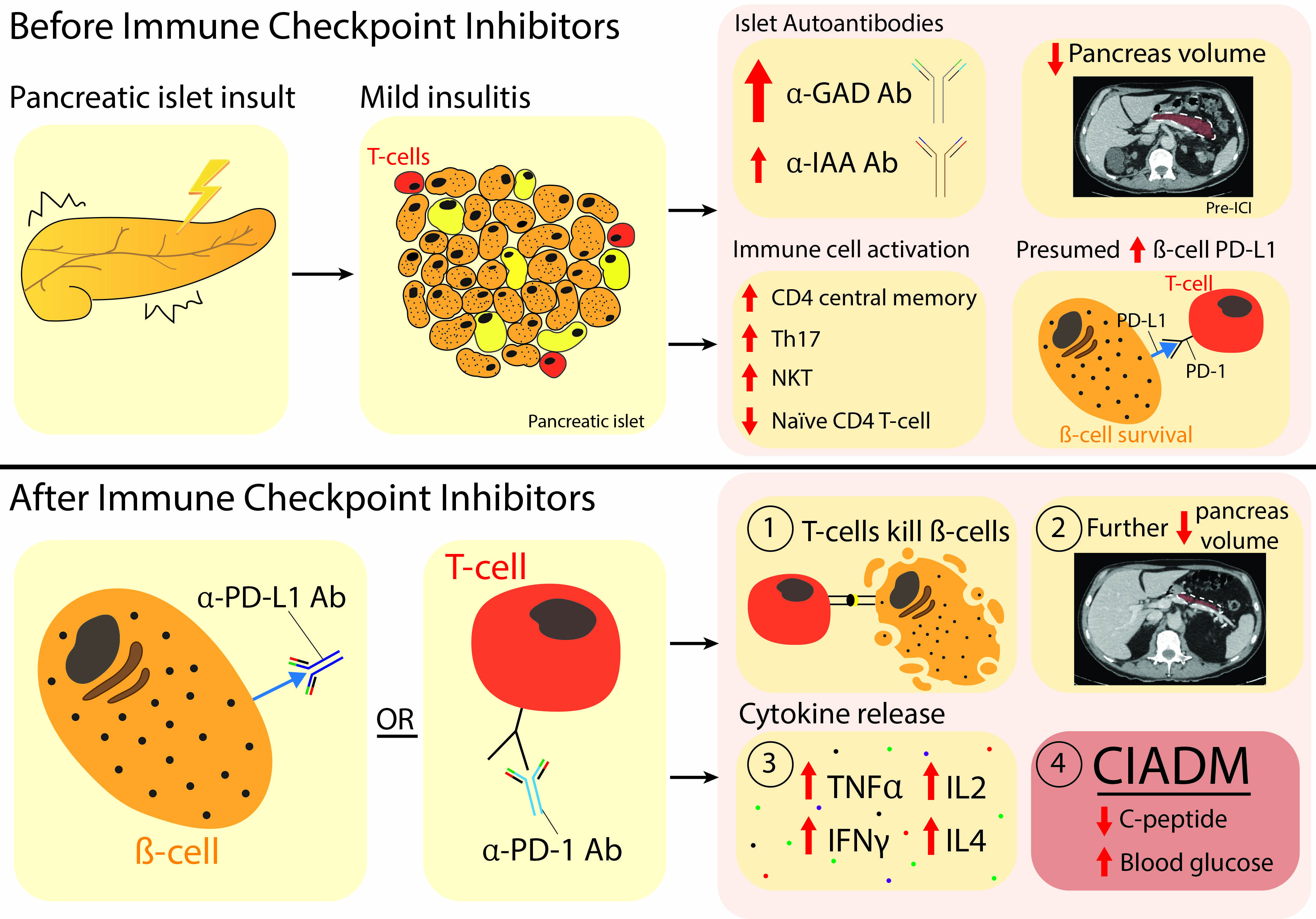

Immune checkpoints are proteins that stop an immune response from killing cells. Cancers cells are often able to manipulate these checkpoints so they can avoid being destroyed by the immune system and continue to proliferate. ICI therapy prevents the ‘stop’ signal from being sent, allowing the immune system to kill the cancer cells.

However, in some people, the ICI therapy leads to the immune system killing healthy cells – like the insulin producing cells in the pancreas. If that happens, people get lifelong insulin dependent diabetes. This is known as checkpoint inhibitor-associated autoimmune diabetes (CIADM). If glucose levels get dangerously high or remain high for too long, it can lead to life-threatening complications like diabetic ketoacidosis. Long term, diabetes also can cause permanent damage to the eyes, nerves, kidneys and blood vessels.

Patients often develop CIADM really quickly – half the cases have already happened 3 months after starting ICI therapy and, so far, no patient who has developed CIADM has recovered insulin control.

The research

Using samples from the Melanoma Institute of Australia biobank, the WIMR team analysed CIADM blood samples and CT scans from CIADM patients before and after starting ICI treatment, as well as control patients who also were treated with ICI but did not develop CIADM.

Professor Gunton says, “Before ICI treatment, patients who went on to develop CIADM had smaller volume of their pancreas on CT scan, and higher anti-GAD antibodies in their blood tests. They also had varying levels (mostly higher) of circulating immune white cells (T cell subsets). These white blood cells are normally crucial for a healthy immune response, but in CIADM, they target and kill the insulin-producing cells.

“After ICI therapy, CIADM patients had an even smaller pancreatic volume, and an increase in activated circulating CD4+ T cells.”

Professor Gunton says the research shows that those who develop CIADM are immunologically predisposed even before their first dose of checkpoint inhibitor. “We can use these test results to accurately predict who will get CIADM with excellent sensitivity”.

“These findings can be used to guide ICI use and help with better monitoring to reduce the serious complications of CIADM. The findings might also change the oncologists risk-benefit thinking for low-risk tumours. In other words, if a person has a low-risk tumour but would have a >90% chance of getting permanent insulin-requiring diabetes, it would be better to use a different cancer treatment for that patient.

“There are a number of research studies underway looking to prevent type 1 diabetes, and we hope that now people at high risk of CIADM can be identified, that this could lead to future studies of therapies to prevent CIADM in high-risk patients.”

Multimedia

Australia; NSW; VIC

Australia; NSW; VIC