News release

From:

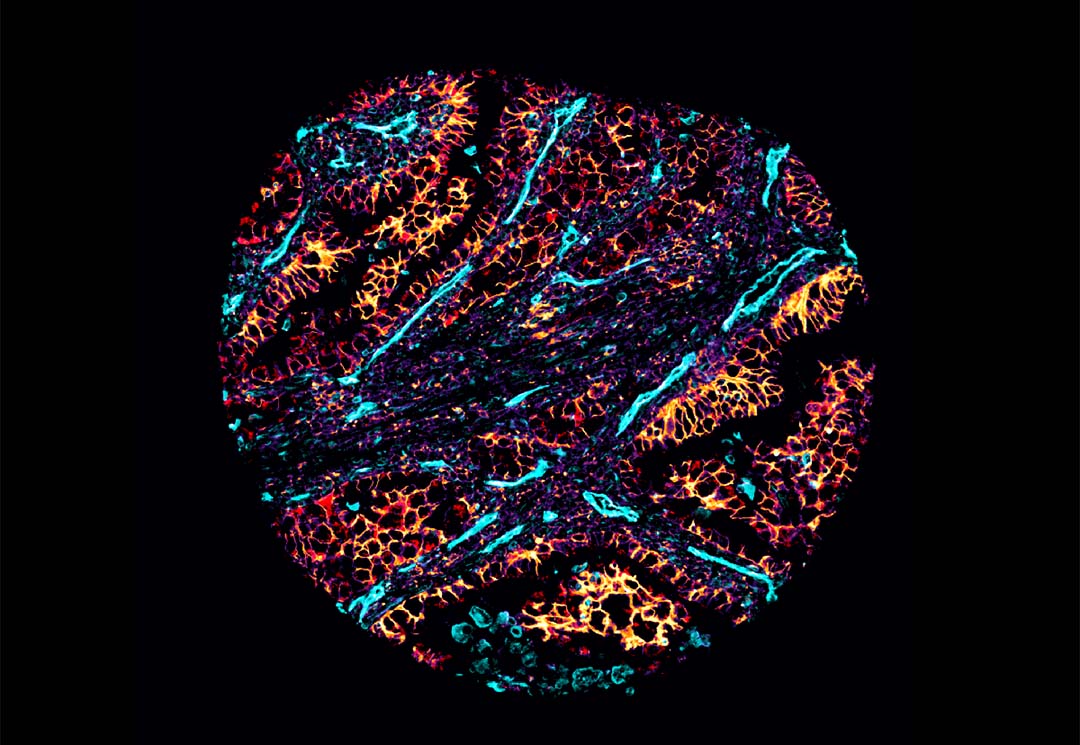

University of Queensland researchers who mapped cancer cell ‘neighbourhoods’ in the most common type of lung cancer have found cell metabolism plays a critical role in determining how lung cancer patients will respond to immunotherapy.

Associate Professor Arutha Kulasinghe from UQ’s Frazer Institute said machine learning algorithms and computational approaches were used to examine cell interactions at cellular resolution in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) to better understand why some patients don’t respond to immunotherapy treatment.

“Building on research published last year that mapped lung cancer cells, this study examined how cells interact and metabolise glucose, which is something we know cancer cells thrive on,” Dr Kulasinghe said.

“We were able to dive deep into the complex nature of cells – basically looking at the cells’ personal lives in the complex composition of a tumour – and found certain metabolic neighbourhoods were associated with response and resistance to immunotherapy.

“Immunotherapy is extremely costly and can cost the government more than $400,000 per patient per year, but it often only works in about 20-30 per cent of patients.

“It’s important to understand how to identify these patients, and those that might need combination or alternative therapies.”

Having the ability to predict whether cancer cells will respond to immunotherapy means doctors can provide more targeted treatment, which could lead to better outcomes for lung cancer, which causes around 20,000 deaths in Australia every year.

Lead author Dr James Monkman said the cutting-edge technologies paired with our computational analysis used in the study enabled researchers to see how each cell processed glucose.

“We know cancer cells love sugar, and we analysed where glucose was being processed in the cells and where it wasn’t – you could have a region of a tumour processing glucose in a completely different way to another area of the tumour,” Dr Monkman said.

“Now we’re starting to understand how and where each cancer cell metabolises sugars – and that higher glucose uptake in cancer cells leads to poorer outcomes.

“The next step is to design targeted treatments to make immunotherapy more effective, such as with metabolic inhibitors.

“Our end goal is precision medicine, where we can profile every cell in a patient’s tumour to determine what drug the patient needs based on their unique tumour profile.”

Associate Professor Kulasinghe hopes this research will be expanded to include other tumours including head and neck cancer and some aggressive skin cancers.

The next phase of research will examine how the approach can be incorporated into clinical trials.

This research was an international collaboration involving Wesley Research Institute, Yale School of Medicine, NucleAI and Quanterix.

UQ’s Frazer Institute is based at the Translational Research Institute (TRI).

The research is published in Nature Communications.

Images available via Dropbox.

Australia; QLD

Australia; QLD