Media release

From:

Gigantic, meat-eating dinosaurs didn’t all have strong bites

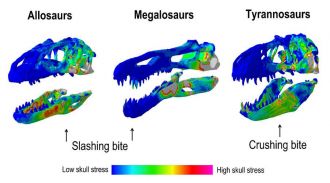

A new analysis of the bite strength of 18 species of carnivorous dinosaurs shows that while the Tyrannasaurus rex skull was optimized for quick, strong bites like a crocodile, other giant, predatory dinosaurs that walked on two legs—including spinosaurs and allosaurs—had much weaker bites and instead specialized in slashing and ripping flesh. Reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on August 4, these findings demonstrate that meat-eating dinosaurs followed different evolutionary paths in terms of skull design and feeding style despite their similarly gigantic sizes.

“Carnivorous dinosaurs took very different paths as they evolved into giants in terms of feeding biomechanics and possible behaviors,” said Andrew Rowe of the University of Bristol, UK.

“Tyrannosaurs evolved skulls built for strength and crushing bites, while other lineages had comparatively weaker but more specialized skulls, suggesting a diversity of feeding strategies even at massive sizes. In other words, there wasn’t one ‘best’ skull design for being a predatory giant; several designs functioned perfectly well.”

Rowe has always been fascinated by big carnivorous dinosaurs, and he considers them interesting subjects for exploring basic questions in organismal biology. In this study, he and co-author Emily Rayfield wanted to know how bipedalism—or walking on two legs—influenced skull biomechanics and feeding techniques.

It was previously known that despite reaching similar sizes, predatory dinosaurs evolved in very different parts of the world at different times and had very different skull shapes. For Rowe and Rayfield, those facts raised questions about whether their skulls were functionally similar under the surface or if there were notable differences in their predatory lifestyles. As there are no massive, bipedal carnivores alive today—ever since the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event—the authors note that studying these animals offers intriguing insights into a way of life which has since disappeared.

To examine the relationship between body size and skull biomechanics, the authors used 3D technologies including CT scans and surface scans analyze the skull mechanics, quantify the feeding performance, and measure the bite strength across 18 species of therapod, a group of carnivorous dinosaurs ranging from small to giant. While they expected some differences between species, they were surprised when their analyses showed clear biomechanical divergence.

“Tyrannosaurids like T. rex had skulls that were optimized for high bite forces at the cost of higher skull stress,” Rowe says. “But in some other giants, like Giganotosaurus, we calculated stress patterns suggesting a relatively lighter bite. It drove home how evolution can produce multiple 'solutions' to life as a large, carnivorous biped.”

Skull stress didn’t show a pattern of increase with size. Some smaller therapods experienced greater stress than some larger species due to increased muscle volume and bite forces. The findings show that being a predatory biped didn’t always equate to being a bone-crushing giant. Unlike T. rex, some dinosaurs, including the spinosaurs and allosaurs, became giants while maintaining weaker bites more suited for slashing at prey and stripping flesh.

“I tend to compare Allosaurus to a modern Komodo dragon in terms of feeding style,” Rowe says. “Large tyrannosaur skulls were instead optimized like modern crocodiles with high bite forces that crushed prey. This biomechanical diversity suggests that dinosaur ecosystems supported a wider range of giant carnivore ecologies than we often assume, with less competition and more specialization.”

Multimedia

International

International