News release

From:

Human nasal passages defend against the common cold and help determine how sick we get

When a rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of the common cold, infects the lining of our nasal passages, our cells work together to fight the virus by triggering an arsenal of antiviral defenses. In a paper publishing January 19 in the Cell Press journal Cell Press Blue, researchers demonstrate how the cells in our noses work together to defend us from the common cold and suggest that our body’s defense to rhinovirus—not the virus itself—typically predicts whether or not we catch a cold, as well as how bad our symptoms will be.

“As the number one cause of common colds and a major cause of breathing problems in people with asthma and other chronic lung conditions, rhinoviruses are very important in human health,” says senior author Ellen Foxman of Yale School of Medicine. “This research allowed us to peer into the human nasal lining and see what is happening during rhinovirus infections at both the cellular and molecular levels.”

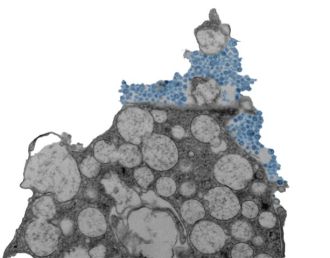

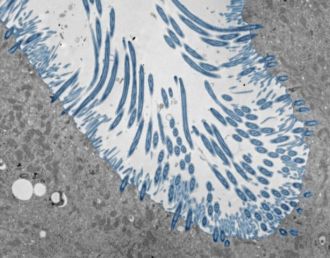

To do so, the researchers created lab-grown human nasal tissue. They cultured human nasal stem cells for four weeks while exposing the top surface to air. Under these conditions, the stem cells differentiated into a tissue with many of the cell types that are found in the human nasal passages and lining of the lung airways, including cells that produce mucus and cells with cilia—moving hair-like structures that sweep mucus out of the lungs.

“This model reflects the responses of the human body much more accurately than the conventional cell lines used for virology research,” Foxman says. “Since rhinovirus causes illness in humans but not other animals, organotypic models of human tissues are particularly valuable for studying this virus.”

The model allowed the team to examine the coordinated responses of thousands of individual cells at once and test how the responses changed when the cellular sensors that detect rhinovirus were blocked. In doing so, the researchers observed a defensive mechanism that keeps rhinovirus infections at bay, coordinated by interferons—proteins that block the entry and replication of viruses.

Upon sensing rhinovirus, cells in the nasal lining produce interferons, which induce a coordinated antiviral defense of infected cells and neighboring cells, making the environment inhospitable for viral replication. If the interferons act quickly enough, the virus cannot spread. When the researchers prevented this response experimentally, the virus quickly infected many more cells, causing damage and, in some cases, death of the infected organoids.

“Our experiments show how critical and effective a rapid interferon response is in controlling rhinovirus infection, even without any cells of the immune system present,” says first author Bao Wang of Yale School of Medicine.

The research also revealed other responses to rhinovirus that kick in when viral replication increases. For example, rhinovirus can trigger a different sensing system that causes infected and uninfected cells to synergistically produce excessive mucus, increase inflammation, and sometimes cause breathing problems in the lungs. These responses may be good targets for intervening in rhinovirus infection and promoting a healthy antiviral response, say the researchers.

The team acknowledges that the organoids used contain limited cell types compared to those in the body, since in the body an infection attracts other cells, including those in the immune system, to join the defense against rhinovirus infection. They say that understanding how other cell types and environmental factors in the nasal passages and airways calibrate the body’s response to rhinovirus infection is an important next step of this work.

“Our study advances the paradigm that the body’s responses to a virus, rather than the properties inherent to the virus itself, are hugely important in determining whether or not a virus will cause illness and how severe the illness will be,” Foxman says. “Targeting defense mechanisms is an exciting avenue for novel therapeutics.”

Multimedia

International

International