News release

From:

A new discovery about how cells communicate with each other in the body’s immune system has revealed deeper insights for an international team of scientists into fundamental immune system function.

The new study, published in Nature Communications, overturns a long held understanding about how T cells – white blood cells that make up a key part of the immune system – recognise lipid antigens, a chemical class of molecules that make up cell membranes.

Lipids are presented to T cells by a distinct family of molecules called CD1, yet one member of this family, CD1c, has remained poorly understood despite its significant role in human immunity.

For more than 30 years, scientists considered that antigens were displayed to T cells in a simple, upright position, pointing directly towards the T cell. This “end-to-end” arrangement was considered a universal rule governing how immune cells recognise threats.

Now, researchers from Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) and the Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital, together with collaborators from the University of Melbourne and the University of Oxford, have challenged long-held assumptions about how immune recognition works.

Challenging rules in immunology

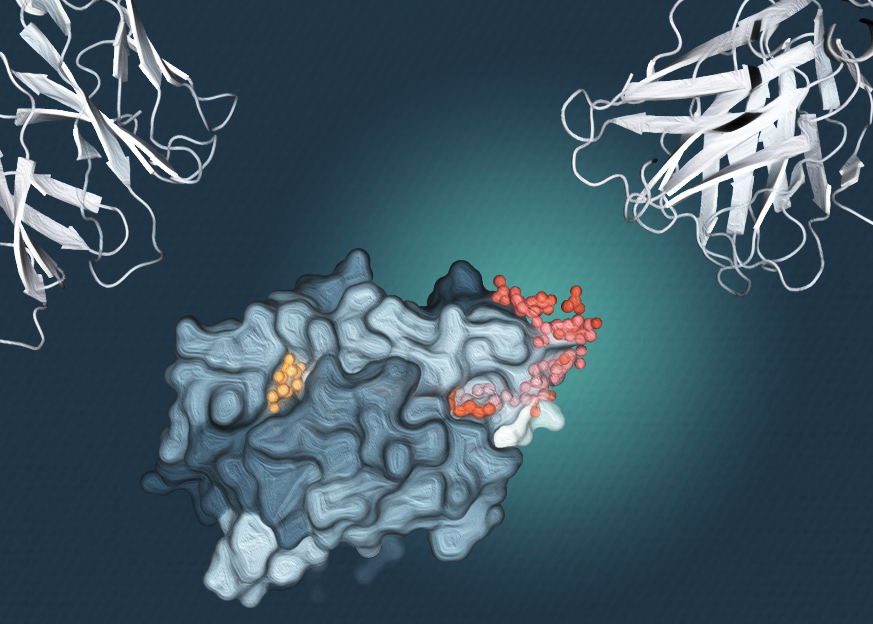

Using high resolution imaging the research team discovered that CD1c can display lipid molecules in an unexpected sideways orientation. Dr Adam Shahine, a NHMRC research fellow at Monash BDI, said the discovery reveals that antigen presentation is not governed by a single rigid set of rules, but instead can involve different arrangements that expand how the immune system surveys its environment.

“Much of immunology has been built around the idea that immune recognition follows one fixed arrangement,” Dr Shahine said. “This work shows that the immune system is more flexible than we assumed, and that there are additional ways immune cells can ‘see’ what’s around them.”

Rather than interfering with immune recognition, the sideways positioning allows T cells to scan CD1c effectively.

The findings show that CD1c can handle larger lipid molecules by allowing part of the molecule to extend out to the side, while remaining visible to T cells.

This new antigen display model does not merely hold for a single type of lipid. Dr Tan-Yun Cheng has demonstrated that mass spectrometry could be used to directly detect CD1c binding to dozens of lipid types, with the patterns of lipids displayed suggesting this new model could be broadly used in the CD1c system.

First author Dr Thinh-Phat Cao said that the findings highlight CD1c as a complex molecular player with unique properties in immune recognition.

“Using data collected at the ANSTO Australian Synchrotron, we found that CD1c can hold multiple lipids in place at the same time, in unique configurations, but can position them in a manner that still allows immune cells to engage,” Dr Cao said.

“That flexibility helps explain how the immune system can deal with such a wide variety of lipid molecules, shaping immune responses in unexpected ways.”

What this means for future breakthroughs on health and disease

Lipids are abundant throughout the body and play important roles in normal physiology and disease. Understanding how the immune system recognises these molecules is essential for building a more complete picture of immune function.

By revealing a new way lipids can be displayed to immune cells, the study helps explain how immune recognition can extend beyond traditional models based on proteins alone.

While this research is driven by fundamental discovery, it also lays important groundwork for future studies exploring how lipid recognition contributes to health and disease.

At Monash University, this work is supported by growing international collaborations, including through the Monash Boston Hub, which strengthens research connections between Australia and the United States.

By bringing together basic scientists and clinical researchers, these partnerships help ensure that foundational discoveries, such as this new understanding of lipid immunity, can be explored further in human disease over time.

Understanding this could lead to new strategies for diagnostics and targeted therapies.

“This discovery opens new avenues to better understand how diseases where lipids play a role,” Dr Shahine said.

“This could aid in the design of treatments that are better matched to how the body responds to disease.”

Read the full publication, “Sideways lipid presentation by the antigen-presenting molecule CD1c”, in Nature Communications: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67732-2

This research has been supported with funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

For more Monash media stories, visit our news and events site

ABOUT THE MONASH BIOMEDICINE DISCOVERY INSTITUTE

Committed to making the discoveries that will relieve the future burden of disease, the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) at Monash University brings together more than 120 internationally-renowned research teams. Spanning seven discovery programs across Cancer, Cardiovascular Disease, Development and Stem Cells, Infection, Immunity, Metabolism, Diabetes and Obesity, and Neuroscience, Monash BDI is one of the largest biomedical research institutes in Australia. Our researchers are supported by world-class technology and infrastructure, and partner with industry, clinicians and researchers internationally to enhance lives through discovery.

Australia; VIC

Australia; VIC