Media release

From:

New research from the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney has uncovered a new biological pathway that may help explain why people with type 2 diabetes are more prone to developing dangerous blood clots, potentially paving the way for future treatments that reduce their cardiovascular risk.

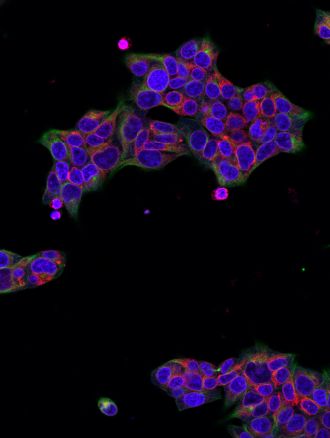

The study, led by Associate Professor Freda Passam from the Central Clinical School and Associate Professor Mark Larance from the School of Medical Sciences, was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. A protein called SEC61B has been found to be significantly increased in the platelets of people with type 2 diabetes. The protein appears to disrupt calcium balance inside platelets, making them more likely to clump together and form clots.

Importantly, the researchers showed that blocking SEC61B activity with an antibiotic – anisomycin – reduced platelet clumping in human samples and animal models.

“People living with type 2 diabetes are vulnerable to increased risk of blood clots,” said Associate Professor Passam. “These exciting findings identify a whole new way to reduce this risk and help prevent life-threatening complications like heart attack and stroke.”

In Australia alone, nearly 1.2 million people were living with type 2 diabetes in 2021. The condition is more prevalent in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and in rural and regional communities.

“Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death in this group, partly due to the heightened activity of platelets – the tiny blood cells that help form clots. This heightened platelet sensitivity to clotting also makes traditional anti-coagulant treatments less effective in people with type 2 diabetes, limiting the options to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.”

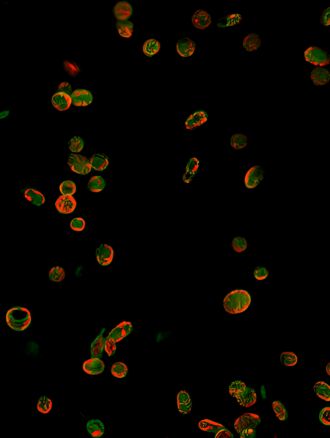

The research team used advanced proteomic techniques to study human and mouse platelets, discovering that SEC61B contributes to calcium leakage from stores of the mineral within platelets, which in turn makes platelets more reactive.

While treatments targeting SEC61B are still in early stages, the researchers believe pre-clinical trials in animals could begin within 1–2 years, with potential therapies for patients on the horizon in the next decade.

Multimedia

Australia; NSW

Australia; NSW