News release

From:

Astrobiology: Potential microbial habitats in Martian ice *IMAGES*

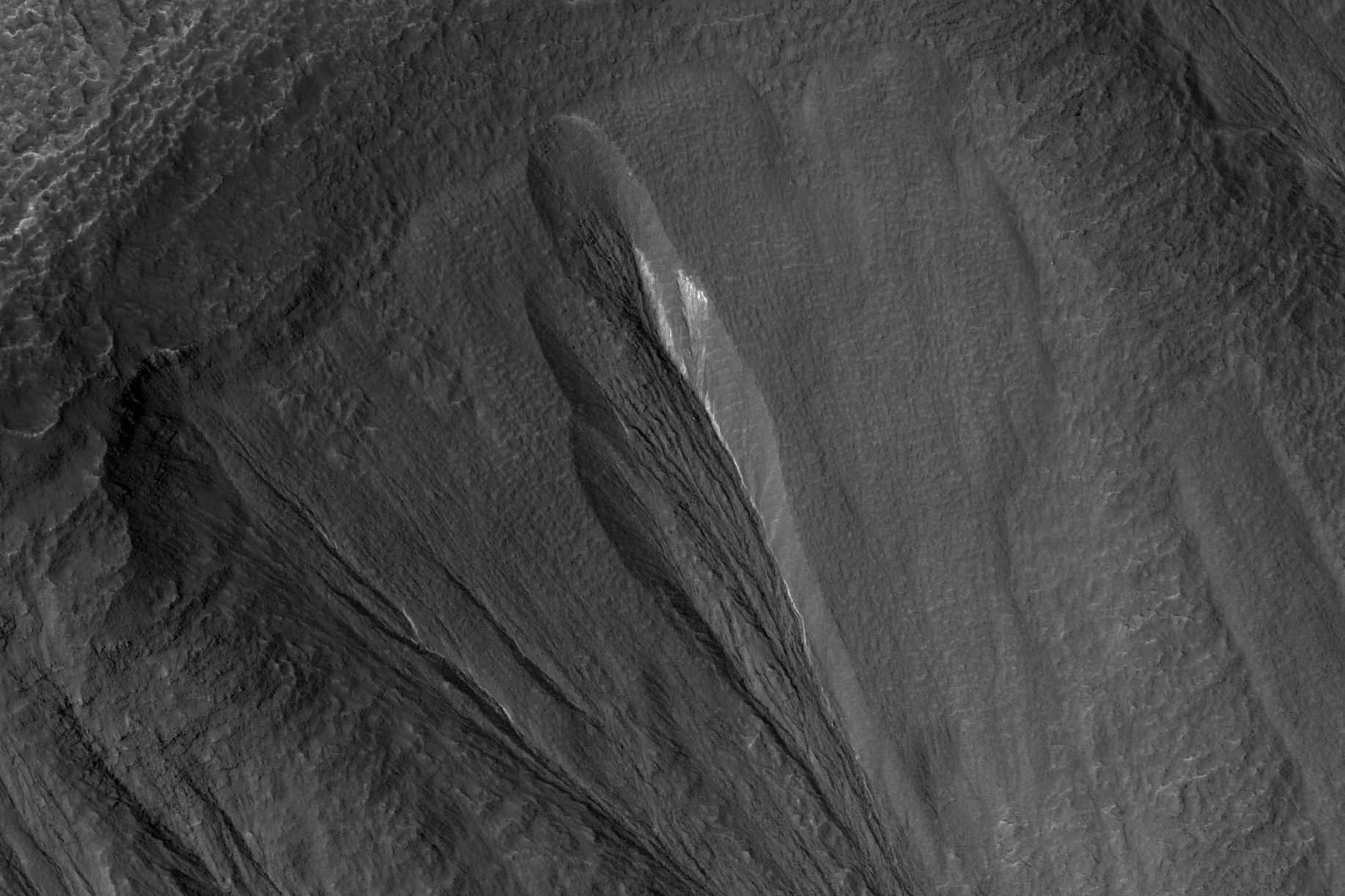

Dusty ice exposed at the surface of Mars could provide the conditions necessary for the presence of photosynthetic life, according to a modelling study. The findings, published in Communications Earth & Environment, suggest that ice deposits located in the planet’s mid-latitudes should be a key location in any search for life on Mars.

High levels of harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun make current life on the surface of Mars almost certainly impossible. However, a sufficiently thick layer of ice can absorb this radiation and could protect cells living below its surface. Any life in these conditions would need to be in a so-called radiative habitable zone — shallow enough to receive enough visible light for photosynthesis, but deep enough to be protected from the ultraviolet radiation.

Aditya Khuller and colleagues calculated whether such a radiative habitable zone could exist in ice with the dust content level and structure of the ice observed on Mars. They found that very dusty ice would block too much sunlight, but that in ice containing 0.01–0.1% dust, a habitable region could potentially exist at depths between 5 and 38 centimetres (depending on the size and purity of the ice crystals). In cleaner ice, a larger habitable zone could exist between 2.15 and 3.10 metres deep. The authors explain that dust particles within the ice could cause occasional localised melting at depths of up to approximately 1.5 metres, providing the liquid water necessary for any photosynthetic life to survive. They suggest that the polar regions on Mars would be too cold for this process, but that subsurface melting could occur in mid-latitude areas (between approximately 30 and 50 degrees latitude).

The authors caution that the potential existence of theoretically habitable zones does not mean that photosynthetic life is, or has ever been, present on Mars. However, it does suggest that the few instances of exposed ice in the Martian mid-latitudes could be key areas for future searches for life to focus on.

Multimedia

International

International