Media release

From:

Developmental biology: Functional eggs generated from human skin cells

Human skin cells can be used to produce fertilizable eggs according to research published in Nature Communications. The proof-of-concept study provides evidence that cell reprogramming could be a viable route in humans for addressing infertility, although further research is needed to ensure efficacy and safety before future clinical applications.

Infertility affects millions of individuals worldwide and can be caused by dysfunction in or absence of one of the two sex cells (gametes) — the oocyte (egg) or the sperm — needed to produce a zygote (a fertilized egg). In some cases, conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF) can be ineffective. A potential alternative approach could be somatic cell nuclear transfer — a process by which the nucleus from one of a patient’s own somatic cells (such as skin cells) is transplanted into a donor egg cell with the nucleus removed, enabling the cell to differentiate into a functional oocyte. However, while standard gametes have half the usual number of chromosomes (one set of 23), cells generated from somatic cell nuclear transfer contain two sets of human chromosomes (46), which would cause subsequent zygotes to have an extra set of chromosomes. A method to remove the extra set of chromosomes has been developed and tested in mouse models; however, it has yet to be demonstrated using human cells.

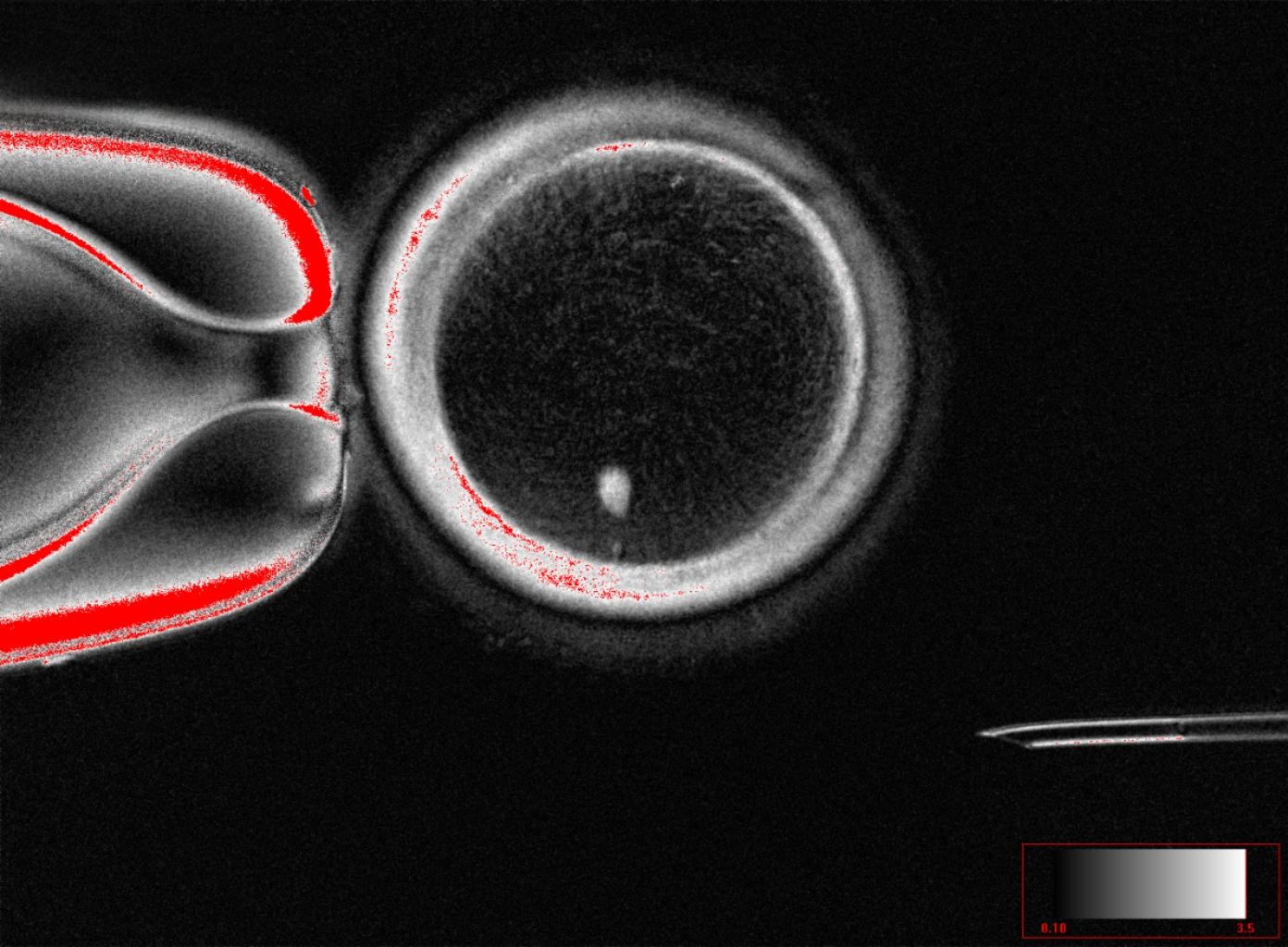

Shoukhrat Mitapilov and colleagues removed the nucleus of somatic skin cells and inserted them into donor oocytes with their nucleus removed. The authors then resolve the problem of the extra set of chromosomes by inducing a process they have termed "mitomeiosis", which mimics natural cell division and causes one set of chromosomes to be discarded, leaving a functional gamete. The process was able to produce 82 functional oocytes, which were then fertilized using sperm in the lab. A small proportion of these fertilized eggs (approximately 9%) went on to develop, by day 6 post-fertilization, to the blastocyst stage of embryo development. However, no blastocysts were cultured beyond this point, which coincides with the time at which they would usually be transferred to the uterus in IVF treatment.

The authors note several limitations in their study, such as most of the embryos not progressing beyond fertilization and the presence of chromosomal abnormalities in the blastocysts. However, this proof-of-concept study shows that this process is potentially feasible in human cells, paving the way for further research into the technique.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) enables the direct reprogramming of somatic cells into functional oocytes, albeit with a diploid genome. To address ploidy reduction, we investigated an experimental reductive cell division process, termed mitomeiosis, wherein non-replicated (2n2c) somatic genomes are prematurely forced to divide following transplantation into the metaphase cytoplasm of enucleated human oocytes. However, despite fertilization with sperm, SCNT oocytes remained arrested at the metaphase stage, indicating activation failure. Artificial activation using a selective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor successfully bypassed this arrest, inducing the segregation of somatic chromosomes into a zygotic pronucleus and a polar body. Comprehensive chromosome tracing via sequencing revealed that homologous chromosome segregation occurred randomly and without crossover recombination. Nonetheless, an average of 23 somatic chromosomes were retained within the zygote, demonstrating the feasibility of experimentally halving the diploid chromosome set. Fertilized human SCNT oocytes progressed through normal embryonic cell divisions, ultimately developing into embryos with integrated somatic and sperm-derived chromosomes. While our study demonstrates the potential of mitomeiosis for in vitro gametogenesis, at this stage it remains just a proof of concept and further research is required to ensure efficacy and safety before future clinical applications.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Prof Roger Sturmey, Professor of Reproductive Medicine, University of Hull, UK, said:

"This insightful piece of research demonstrates that the chromosomes of a differentiated adult cell, known as a somatic cell, can be persuaded to undergo a specific kind of nuclear division that would normally be seen only in eggs or in sperm. This offers a new understanding of the intricate molecular processes that control the segregation of chromosomes in the egg, during the stages immediately before the egg is fertilised.

"This is important, because it opens up the possibility of creating functional new egg cells, containing genetic material that can – in principle – be taken from cells from anywhere in the body. This would be a form of in vitro gametogenesis. However, the rates of success reported in the study are comparatively low, and so the prospect of putting all this to clinical use remains distant.

"The science is impressive, and the researchers were careful to seek the necessary review and guidance for their work. At the same time, such research reinforces the importance of continued open dialogue with the public about new advances in reproductive research. Breakthroughs such as this impress upon us the need for robust governance, to ensure accountability and build public trust."

Prof Ying Cheong, Professor of Reproductive Medicine and Honorary Consultant in Reproductive Medicine and Surgery, University of Southampton, UK, said:

“For the first time, scientists have shown that DNA from ordinary body cells can be placed into an egg, activated, and made to halve its chromosomes, mimicking the special steps that normally create eggs and sperm. This breakthrough, called mitomeiosis, is an exciting proof of concept. In practice, clinicians are seeing more and more people who cannot use their own eggs, often because of age or medical conditions. While this is still very early laboratory work, in the future it could transform how we understand infertility and miscarriage, and perhaps one day open the door to creating egg- or sperm-like cells for those who have no other options.”

Prof Richard Anderson, Elsie Inglis Professor of Clinical Reproductive Science, Deputy Director of MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, University of Edinburgh, UK, said:

“Many women are unable to have a family because they have lost their eggs, which can occur for a range of reasons including after cancer treatment. The ability to generate new eggs would be a major advance, and this study shows that the genetic material from skin cells can be used to generate an egg-like cell with the right number of chromosomes to be fertilised and develop into an early embryo. There will be very important safety concerns but this study is a step towards helping many women have their own genetic children.”

International

International