News release

From:

Planetary science: How Saturn’s rings might be keeping up a youthful appearance

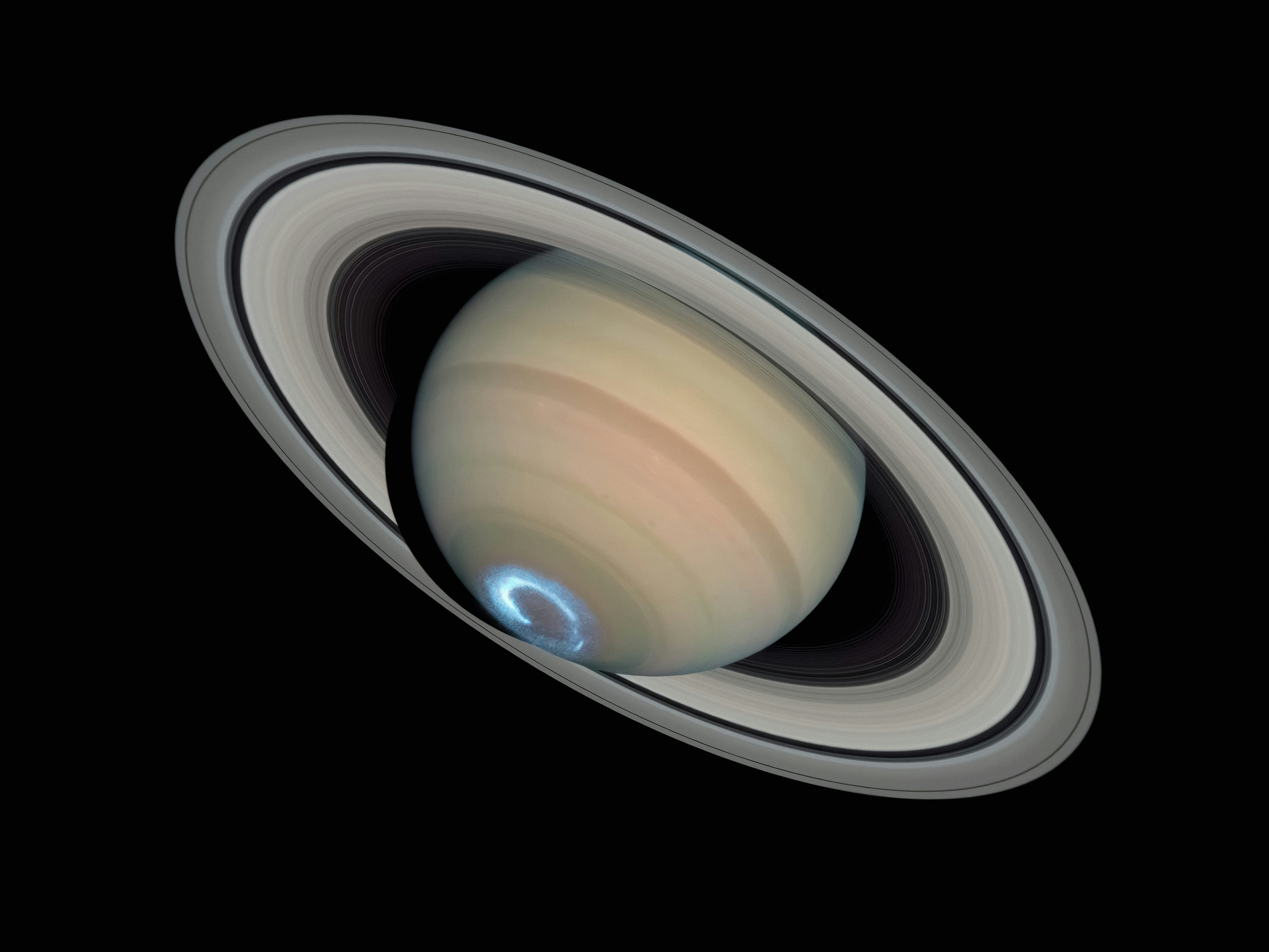

Saturn’s icy rings could be much older than they appear due to their resistance to pollution from impacts with rocky debris, according to a Nature Geoscience paper. The authors suggest that Saturn’s rings may be as old as the planet itself, even though they appear clean and young, challenging previous estimates of their age.

Saturn’s rings were once thought to be ancient, perhaps formed at the same time as the planet itself — approximately 4.5 billion years ago. Over time, impacts with micrometeoroids (rocky debris smaller than a grain of sand travelling through space) are thought to dirty and darken the rock and ice particles that make up the rings. However, when the Cassini spacecraft reached Saturn in 2004, it observed that Saturn’s rings appear to be relatively bright and clean. As such, research has estimated that Saturn’s rings are younger than 400 million years old.

Ryuki Hyodo and colleagues simulated collisions between micrometeoroids and icy ring particles using computer models. They found that high-speed impacts can lead to vaporisation of the micrometeoroids, with the vapour then expanding, cooling, and condensing within Saturn’s magnetic field to form charged nanoparticles and ions. Hyodo and colleagues’ simulations revealed that these charged particles then either collide with Saturn, are dragged into its atmosphere, or escape the gravitational pull of the planet entirely. As a result, the authors suggest that very little of this material is deposited onto the rings, keeping them in relatively clean condition. They suggest that very low levels of pollution may mean that Saturn’s rings are actually billions of years old and are simply maintaining a more youthful appearance.

Although further research is required, the authors suggest that this process could potentially also be occurring in the rings of Uranus and Neptune, as well as on icy moons around giant planets.

International

International