Media release

From:

First use of stem cells to study a genetic cause of blindness

Researchers at the Eye Genetics Research Unit at Children’s Medical Research Institute (CMRI) are the first in the world to use stem cells to study one of the genetic causes of Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA) — a rare condition that causes severe vision loss in babies and young children. Their findings suggest that gene therapy could soon help prevent blindness in affected kids.

The study by Dr To Ha Loi and colleagues, published in Stem Cell Reports, focused on a gene called RPGRIP1, which is important for developing and maintaining the eye’s photoreceptor cells — the light-sensing cells that allow us to see. When this gene is faulty, children can develop severe and currently incurable retinal disease.

Doctors often rely on a database called ClinVar to connect specific gene changes to health conditions. But nearly half of the known RPGRIP1 gene variants are listed as having “uncertain significance,” meaning it’s hard for families to get clear answers about diagnosis or whether their child might qualify for clinical trials or future gene therapies.

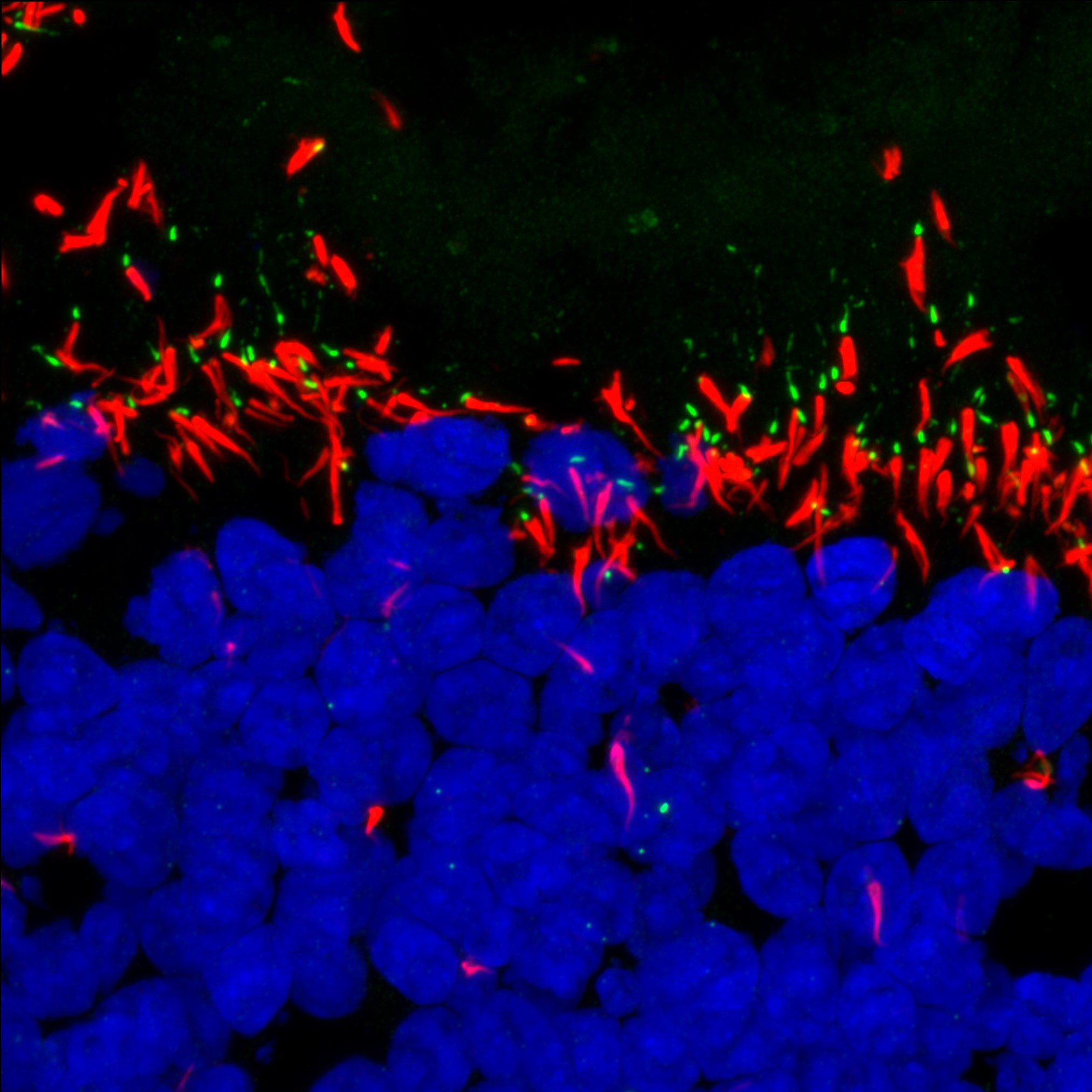

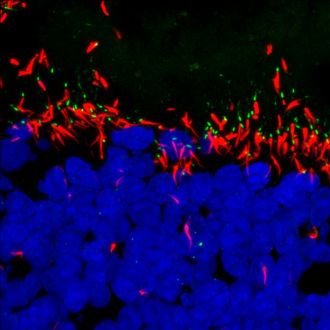

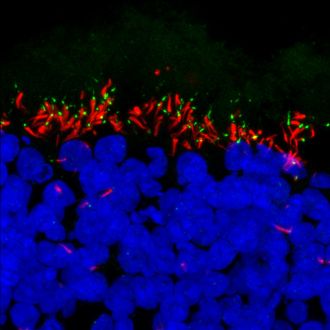

To tackle this, the CMRI team used stem cell–derived 3D retinal organoids — miniature, lab-grown versions of the human retina. These allowed scientists to recreate the effects of RPGRIP1-related disease in the lab. Using these models, they were able to study how and why the disease develops.

Professor Robyn Jamieson, head of the Eye Genetics Research Unit, explained that this is the first time such retinal models have been used to study RPGRIP1 disease using both patient-derived and genetically engineered cells.

“Our findings suggest that even in children who lose vision early, the overall structure of the retina appears preserved, meaning gene therapy may still have the potential to restore sight.

In the past, researchers have studied this condition in mice. In contrast, these new human organoids are an essentially unlimited resource and offer a much more accurate way to study genetic eye diseases.

“Together, the results provide strong hope that gene therapy could eventually transform the lives of children living with LCA, offering possibilities for treatments where none currently exist,’’ Prof Jamieson said.

This research was conducted in partnership with the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, and the Save Sight Institute at the University of Sydney.

Multimedia

Australia; NSW

Australia; NSW