Media release

From:

Attitudes, not income, drive energy savings at home

Some people flip off the lights the moment they leave a room, while others rarely think twice about saving energy. According to the most comprehensive analysis of people’s sentiments toward household energy savings to date, publishing October 10 in the Cell Press journal Cell Reports Sustainability, people’s attitudes and moral sentiments about their energy usage—rather than income or knowledge of how to conserve power—determine whether they take action at home.

Domestic energy usage accounts for about a fifth of all energy consumption in the United States and European Union. Understanding what matters to people in their energy decision-making could have a large impact on reducing emissions related to energy consumption, says first author Steph Zawadzki of the Northern New Mexico College, USA.

“If we can tap into these deeper psychological factors, our research suggests that this is a pathway to get as many people as possible engaged in saving energy,” says Zawadzki.

To understand what drives people’s energy-saving behaviors at home, the researchers analyzed 100 existing studies scattered across the fields of psychology, sociology, economics, and engineering. In total, these studies included perspectives from more than 430,000 people across 42 countries.

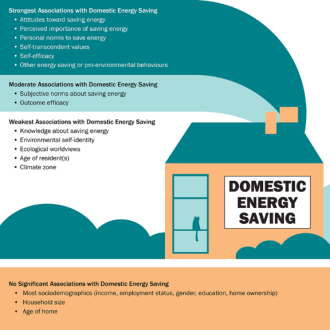

Because prior studies explored a diverse range of behaviors and outcomes, the team examined a total of 26 psychological and sociodemographic factors and investigated how effective each factor was in determining whether people take energy-saving actions.

They found that people were more likely to save energy if they had a positive attitude toward conserving electricity. For some, that meant recognizing that what they do at home makes a difference, while for others, it was about doing the right thing for the environment.

People also valued how others perceive them. As a result, individuals saved more energy if they thought others expected them to conserve power.

Those who already practiced environmentally friendly habits, such as recycling or using public transportation, were also more inclined to cut energy use at home, suggesting that pro-environmental behaviors could reinforce one another.

The team was surprised to see that understanding the environmental impact of using energy only had a weak effect on energy-saving behaviors. Many socioeconomic factors, such as education and income levels, were also hardly related to energy saving behaviors.

“Knowing what to do is often not enough to actually make someone change their behavior. You have to also tap into deeper attitudes, preferences, and desires to actually motivate people to follow through with their actions,” Zawadzki says.

The researchers hope that their findings provide evidence for policymakers to design effective public programs for curbing household emissions. For example, the analysis suggests that programs that help people feel good about energy saving can increase their effectiveness.

“The vast majority of people, regardless of their backgrounds, generally want to do the right thing. We’re not trying to change hearts and minds, but activate feelings people already have,” Zawadzki says. “As we are trying to address the urgent climate crisis, we need to add these crucial tools that were missing to our climate-mitigation arsenal.”

Multimedia

International

International