Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Associate Professor Suman Majumdar is Chief Health Officer of COVID and Health Emergencies at the Burnet Institute

Despite significant success in controlling a polio outbreak in 2018 through a mass vaccination campaign, routine immunisation rates, including for polio remain low, which exposes large pockets of unimmunised people, particularly children, who are most susceptible to the disease.

The Papua New Guinean Government has swiftly responded to activate its Polio emergency response plan. The priority now is to roll-out a vaccination campaign, with community engagement, to actively reach people and enhance surveillance and data collection to understand the spread of the virus.

The vaccination is safe and is free of charge in the country.

Oral polio vaccine (OPV) contains a weakened form of polio virus. Outbreaks of the virus occur where vaccination rates are low, particularly in areas that are crowded and have poor sanitation.

Ensuring polio vaccinations are up to date, making sure food and water are prepared hygienically and avoiding close contact with people who may be infectious are the best ways for people to protect themselves against becoming infected with the virus.

Initial symptoms are a flu-like illness (fever, fatigue, muscle pain, sore throat). If the disease progresses to a major illness, severe muscle pain and stiffness of the neck and back and paralysis may occur.

Associate Professor Vinod Balasubramaniam is a Molecular Virologist and the Leader of the Infection and Immunity Research Strength from the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine & Health Sciences at Monash University in Malaysia

What happened in PNG and why is it a concern?

The recent resurgence of poliovirus type 2 in Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a significant public health concern, particularly in light of the country’s previously polio-free status since 2000. This outbreak, detected in two asymptomatic children and confirmed through wastewater surveillance in Lae and Port Moresby, involves a vaccine-derived poliovirus strain linked to Indonesia. Such strains can mutate in under-immunised populations, regaining the capacity to cause disease—a rare but known risk of oral polio vaccines.

Why did the outbreak occur and what are the local vulnerabilities?

PNG’s outbreak reflects the persistent global challenge of maintaining high immunisation coverage. In some regions of PNG, vaccination rates have fallen below 50%, far short of the 95% threshold needed for herd immunity. Contributing factors include healthcare access limitations, misinformation, and under-resourced surveillance systems. With only 8% coverage in certain areas, the risk of undetected transmission and potential paralysis cases remains high.

How could this affect Australia?

For Australians, especially those in northern Queensland and the Torres Strait, this situation underscores the importance of vigilance. While Australia maintains a robust immunisation program—with over 90% coverage among children—and effective sanitation and surveillance, proximity and cross-border travel elevates theoretical risks. Australia’s ongoing support for PNG, including technical assistance and contributions to its national polio response, is essential for regional health security.

What is being done to contain the outbreak?

PNG's response has been swift and comprehensive: two nationwide vaccination rounds targeting 3.5 million children, intensified surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis, and community engagement through trusted local leaders. These actions mirror the successful 2018 outbreak containment, reinforcing that polio can be controlled with prompt and coordinated intervention.

What should Australians do next?

The key message for Australians is clear: panic is unwarranted, but complacency is dangerous. Maintaining high childhood vaccination rates, supporting global immunisation efforts, and combating misinformation are critical. Polio is preventable, but only if communities remain committed to collective action. This outbreak is not just PNG’s challenge—it is a shared responsibility that highlights how interconnected public health truly is.

Jaya Dantas is Professor of International Health in the School of Population Health at Curtin University

The current outbreak of polio in the district of Lae in PNG is of serious concern to PNG, and its neighbours including Australia. The WHO has stated that the cases were detected in wastewater samples and then further confirmed in two healthy children under five. Lae is just 500 kms from Cape York in Northern Queensland and hence alarming to Australia.

Polio is a highly contagious disease caused by the ‘Poliomyelitis virus’ and is spread through saliva and faeces and contaminated water and food. It infects children the most and often there are no symptoms initially, then leading to flu-like symptoms and finally impacting the limbs and muscles and causing paralysis in some cases.

Polio had been eradicated in the world by 2020 with only two countries – Pakistan and Afghanistan impacted by the wild poliovirus type 1 due to conflict and poor vaccination. The outbreak in PNG is linked to an outbreak of Polio in Indonesia. There is no cure for polio and vaccination is the only means of prevention. We need 90% of the children in any country to be vaccinated for ‘herd immunity’ which protects those that are not vaccinated.

The current rates of vaccination among children in PNG is just 50% which is a cause for deep concern and there is a critical and urgent need for WHO, UNICEF, the health department in PNG and its neighbours of Australia and New Zealand to take steps to roll out vaccination for all children in PNG including polio and other childhood infectious diseases, monitor the outbreak, keep the PNG community informed and prevent spread of polio.

Dr Nias Peng is a virologist who study viruses of clinical and veterinary significance.

In May 2025, Papua New Guinea (PNG) declared a polio outbreak following the detection of type 2 poliovirus in wastewater samples from Port Moresby and Lae. Subsequent testing confirmed the virus in two asymptomatic children, suggesting possible community transmission. This resurgence is strongly attributed to low immunisation coverage, where only 47% of children are vaccinated, with some districts as low as 8% as well as inadequate sanitation infrastructure.

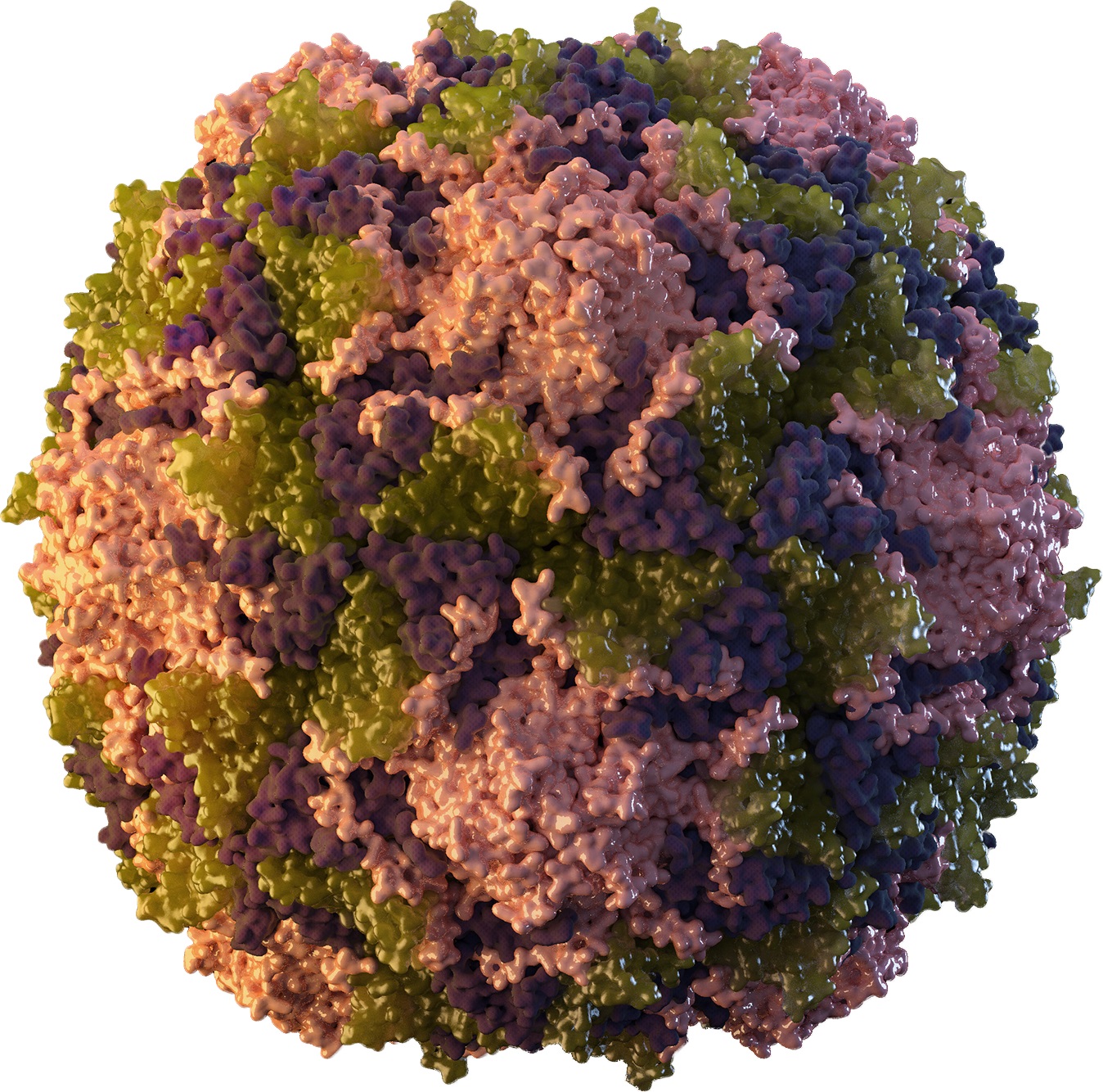

Poliovirus is a highly contagious enterovirus belonging to the Picornaviridae family. It is a non-enveloped virus that primarily affects children under five years of age. It spreads mainly through consumption of food or water contaminated with faecal material of an infected person. Less commonly, the virus can also spread via respiratory droplets from coughs or sneezes. Most people with polio don’t have symptoms, but some people experience acute paralysis that can be permanent, or cause death.

Type 2 wild poliovirus was declared eradicated globally in 2015; however, vaccine-derived strains can emerge in under-immunised populations. In such settings, the attenuated virus from the oral polio vaccine can, although rare, mutate and regain neurovirulence, leading to outbreaks of type 2 poliovirus.

Australia has been polio-free since 2000. While the risk of polio spreading to Australia is considered low due to high vaccination rates and robust public health infrastructure, it is recommended that travellers to PNG ensure their polio vaccinations are up to date. Continued surveillance for poliovirus and support for PNG's immunisation efforts are crucial to contain the outbreak and prevent international spread.

Dr Matt Mason is a Lecturer in Nursing and is the Academic Lead for Work Integrated Learning for the School of health at the University of the Sunshine Coast

Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) recent confirmation of poliovirus circulation in Port Moresby and Lae is a stark reminder that polio remains a regional threat, not just a historical footnote. Environmental surveillance detected type 2 poliovirus in wastewater, and stool samples from two asymptomatic children in Lae confirmed community transmission. With only 47% of PNG children fully immunised, and some districts reporting coverage as low as 8%, pockets of extreme vulnerability exist.

Infection prevention and control (IPC) must begin at the community level. Strengthening water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure in both urban settlements and remote villages is essential to curb faecal–oral spread. Health authorities should collaborate with trusted partners, such as churches and women’s groups, to disseminate hygiene kits and promote hand‑hygiene stations at schools, markets, and health services.

It is imperative that the response rapidly scales‑up. This should include mobile outreach teams to deliver oral polio vaccine (OPV) alongside routine childhood immunisations, especially in Morobe and the National Capital District, where recent detections occurred, and district health centres must receive clear case‑management protocols to isolate suspect acute flaccid paralysis promptly.

Vaccinating health care workers and community volunteers is non‑negotiable. Front‑line staff require full OPV courses and bivalent inactivated polio vaccine (bIPV) boosters to protect themselves and prevent transmission. Combined with targeted social‑mobilisation efforts, using local languages and Pacific storytelling traditions, this approach can rebuild trust and drive uptake. Only through coordinated IPC, WASH, robust service delivery and universal vaccination can PNG and its Pacific neighbours reduce the risk of a resurgence of polio in the region. To enable this it is vitally important that countries and organisations partner with the PNG government to quickly action this response.

Australia; Pacific; QLD; WA; ACT

Australia; Pacific; QLD; WA; ACT