Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Ian Musgrave is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine, School of Medicine Sciences, within the Discipline of Pharmacology at the University of Adelaide.

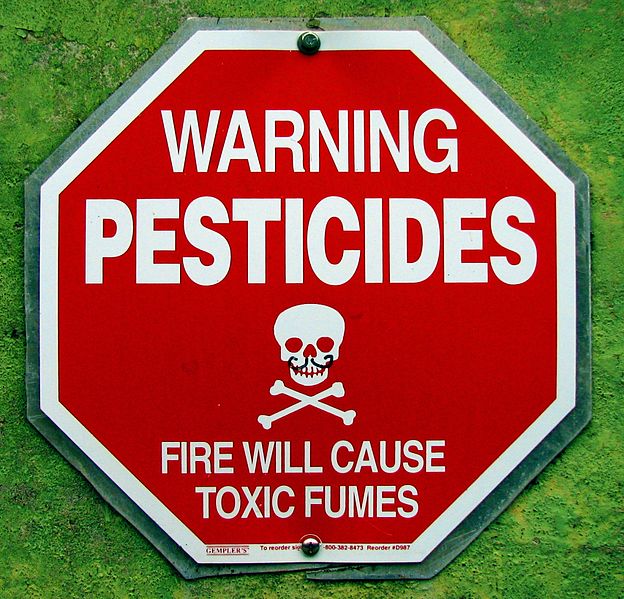

The recent expansion of the range of Zika virus, coupled with its linkage to the rise of microcephaly in Brazil, where babies are born with very small heads, is the focus of international concern. However, a recent report from the group “Physicians in the Crop-Sprayed Villages” has claimed that the outbreak of microcephaly is due to a pesticide used to control the mosquitoes that carry Zika virus. This claim is not plausible. The pesticide in question is pyriproxyfen, a replacement for the organophosphate pesticides that the mosquitoes are becoming resistant to. Pyriproxyfen acts by interfering with the hormonal control growth cycle of insects from hatching, to larvae, to pupa. This hormone control system does not exist in organisms with backbones, such as humans, and pyriproxyfen has very low toxicity in mammals as a result.

An adult human would need to eat a teaspoon full of the raw pesticide to reach the threshold levels for toxicity seen in animals. In terms of how much is present in water reservoirs that have been sprayed with pyriproxyfen to control mosquito larvae, a person would have to drink well over 1,000 litres of water a day, every day, to achieve the threshold toxicity levels seen in animals. The effect of pyriproxyfen on reproduction and fetal abnormalities is well studied in animals. In a variety of animal species even enormous quantities of pyriproxyfen do not cause the defects seen during the recent Zika outbreak. Pyriproxyfen is poorly absorbed by humans and rapidly broken down so even the minute amounts humans would be exposed to via water treatment would be reduced even further. As well, pyriproxyfen is relatively rapidly removed from the environment as well, so overall exposure will be low. The “Physicians in the Crop-Sprayed Villages” only evidence for the role of pyriproxyfen is that spraying began in 2014. While the evidence that Zika virus is responsible for the rise in microcephaly in Brazil is not conclusive, the role of pyriproxyfen is simply not plausible.

Professor Ary Hoffmann is a Australian Laureate Fellow, Department of Genetics & Department of Zoology, University of Melbourne. He researches new pest control options to control mosquitoes

Pyriproxyfen is a widely used chemical in agriculture and in the pet industry and has been around for a while. It is a growth inhibitor of insect larvae. There is no direct evidence that it is associated with human birth defects – insect development is quite different to human development and involves different hormones, developmental pathways and sets of genes, so it cannot be assumed that chemicals affecting insect development also influence mammalian development.

Chemicals can be effective in local Aedes mosquito control, but it is true that the effects often are quite temporary because new mosquitoes will emerge as larvae develop and emerge from breeding containers. This is one reason why public health campaigns often focus on reducing the number of breeding sites around the home, which can be quite an effective control mechanism.

A variety of other options are currently being explored to control mosquitoes or to inhibit their ability to spread disease. The GM mosquito approach represents only one of several possible approaches – for instance, it is also possible to suppress mosquitoes by releasing males that are sterile or incompatible with females from natural populations, without the use of GM. Another possibility is to introduce Wolbachia strains of mosquitoes that reduce viral transmission.

Adjunct Professor Andrew Bartholomaeus is a consultant toxicologist from the School of Pharmacy, University of Canberra and the Therapeutic Research Unit, School of Medicine, University of Queensland

Pyriproxyfen is an insect growth regulator with a mechanism of action that is highly specific to insects. Pyriproxyfen is used on a wide variety of crops and is recommended by the WHO for addition to drinking water storage vessels to prevent the spread of deadly diseases such as malaria.

Studies in rats and rabbits have shown pyriproxyfen to have no reproductive or developmental effects at doses up to at least 100 mg per kg of body-weight every day. This intake would be equivalent to an average human female consuming 6 grams of the compound per day. The acceptable daily intake of pyriproxyfen set by the WHO is 100 micrograms per kg of body-weight per day for a lifetime.

This equates to approximately 6 mg per person per day. By contrast the WHO recommended addition of pyriproxyfen to drinking water storage is a maximum of 10 micrograms per litre which would deliver a daily dose of 20 micrograms. A microgram is one millionth of a gram. Thus, the intake of pyriproxifen in Brazil from treated drinking water is of the order of 300 times lower than the safe limit set by the WHO.

All of this information is readily available to any genuine scientist looking dispassionately at the potential causes of the Zika virus outbreak or the rise in malformations in Brazil. Also readily available is the knowledge that the use of pyriproxifen is driven by WHO recommendations and not the marketing activity of any multinational or other corporation.

The potential human health consequences of discouraging the use of pyriproxyfen in drinking water storage and other mosquito-reduction programs is catastrophic with potential deaths and serious disease from otherwise avoidable malaria, dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases numbered in at least the hundreds of thousands. If these reports and suggestions are motivated by anything other than ignorance and poor scholarship they are deserving of the most strident condemnation.

Journalists covering this story would do well to research the background of those making and reporting the claims as the underlying story and potential public health consequences may be far more newsworthy than the current headlines

Australia; VIC; QLD; SA; ACT

Australia; VIC; QLD; SA; ACT